Flattening the COVID curve: 3 weeks of tougher lockdowns in Sydney's hotspots halved expected case numbers

- Written by Allan Saul, Senior Principal Research Fellow (Honorary), Burnet Institute

In a pandemic, you expect that as new public health measures are introduced, there’s an observable impact on the spread of the disease.

But while that might have been the case in Melbourne’s second wave last year, the highly contagious Delta variant is different. In Sydney’s current second wave, none of the increased restrictions seemed to directly decrease the spread of COVID-19. Until now.

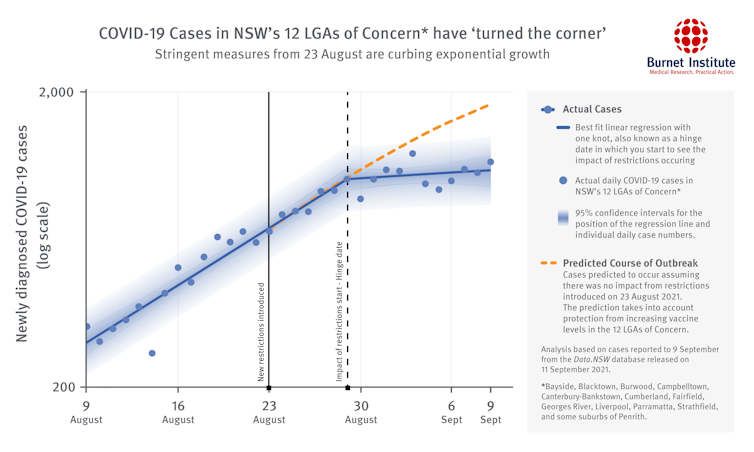

Our modelling shows the curfew with the other restrictions introduced on the August 23 in the 12 local government areas (LGAs) of concern has worked to halt the rise in cases.

And this wasn’t due to the level of vaccinations achieved so far. It suggests other LGAs with rising case numbers should not rely solely on vaccination to cut case numbers in the short to medium term. They may need to tighten restrictions to get outbreaks under control.

What are the tighter restrictions?

Restrictions across Sydney have been in place in various forms since June 23. But daily case numbers only plateaued in the 12 LGAs after the latest round of restrictions were introduced on August 23.

These included:

- a curfew from 9pm to 5am, to reduce the movement of young people

- restricting public access to hardware, garden supplies, office supplies and pet stores to click-and-collect only

- closure of face-to-face teaching and assessment in most educational institutes that remained open

- limiting outdoor exercise to one hour a day.

These came on top of the existing restrictions in these 12 LGAs: only four reasons for leaving home (work/education, care/compassion, shopping for essential supplies, and exercise), 5km travel restrictions and the closure of non-essential shops.

Read more: A tougher 4-week lockdown could save Sydney months of stay-at-home orders, our modelling shows

What impact did these restrictions have?

There was a marked and significant decrease in the growth of the outbreak in the 12 LGAs of concern, starting a week after restrictions were introduced.

The expected growth rate of the Delta variant, in the absence of any controls, has a R0 between 5 and 9. This means one infected person would be expected to pass the virus on to five to nine others.

In the 12 LGAs, the Reff — which takes into account how many others one infected person will transmit the virus to with public health measures in place — reduced from 1.35 to 1.0. That means one case currently infects just one other person.

Cases numbers went from doubling every 11 days to case numbers being constant.

Without the additional restrictions introduced on August 23, the outbreak would have continued with close to an exponential increase (see the dashed orange line in Figure 1 below).

Burnet Institute

Without these stricter measures we expect about 2,000 cases per day by now and about 4,000 per day by the end of the month instead of the 1,000 per day currently in these 12 LGAs.

It’s not possible to assign which specific part or parts of the restrictions package were important, or how they functioned. Nevertheless, it’s encouraging to see a direct association of restrictions and impact on COVID-19 cases.

Vaccination rates have risen, but that’s not the reason

Vaccination rates have steadily risen in the 12 LGAs of concern. Currently, 74-86% of those aged 16 and over have had least one dose, and 34-42% have had both doses.

These vaccination levels have increased substantially in the past month from about 45% with at least one dose and only 22% fully vaccinated.

Read more:

Pfizer vaccinations for 16 to 39-year-olds is welcome news. But AstraZeneca remains a good option

However, taking into account that it takes about two weeks for vaccination to be fully effective, we calculate that from August 23 to September 9, the increased vaccination rates will have only reduced the transmission of COVID by about 9% in the these LGAs. This is nowhere near enough to account for the dramatic change in the case numbers.

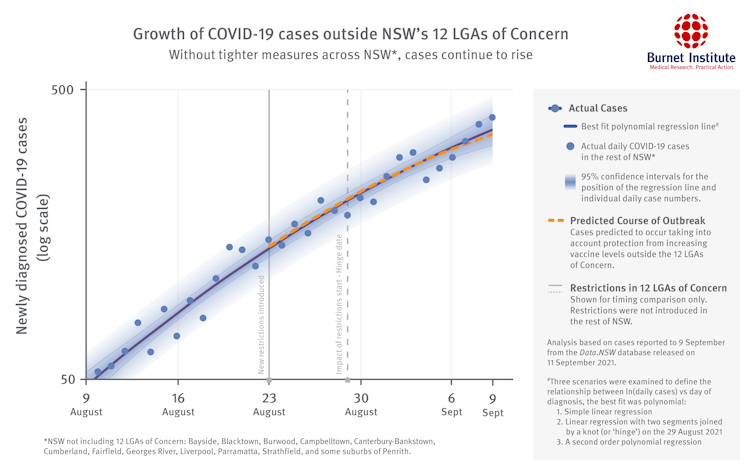

Interestingly, outside these 12 LGAs, there was a gradual slowing of the growth rate that very closely matched the decrease in growth expected from increased vaccine coverage – but no sign of the abrupt change seen in the 12 LGAs of concern.

Burnet Institute

Without these stricter measures we expect about 2,000 cases per day by now and about 4,000 per day by the end of the month instead of the 1,000 per day currently in these 12 LGAs.

It’s not possible to assign which specific part or parts of the restrictions package were important, or how they functioned. Nevertheless, it’s encouraging to see a direct association of restrictions and impact on COVID-19 cases.

Vaccination rates have risen, but that’s not the reason

Vaccination rates have steadily risen in the 12 LGAs of concern. Currently, 74-86% of those aged 16 and over have had least one dose, and 34-42% have had both doses.

These vaccination levels have increased substantially in the past month from about 45% with at least one dose and only 22% fully vaccinated.

Read more:

Pfizer vaccinations for 16 to 39-year-olds is welcome news. But AstraZeneca remains a good option

However, taking into account that it takes about two weeks for vaccination to be fully effective, we calculate that from August 23 to September 9, the increased vaccination rates will have only reduced the transmission of COVID by about 9% in the these LGAs. This is nowhere near enough to account for the dramatic change in the case numbers.

Interestingly, outside these 12 LGAs, there was a gradual slowing of the growth rate that very closely matched the decrease in growth expected from increased vaccine coverage – but no sign of the abrupt change seen in the 12 LGAs of concern.

Burnet Institute

What does this mean for other parts of Sydney?

The gains associated with the more stringent restrictions are readily reversible. If they are lifted before vaccination can permanently reduce growth, COVID-19 cases could rapidly increase again in these 12 LGAs.

Meanwhile, COVID-19 cases outside the 12 LGAs of concern continue to grow strongly. With the current restrictions in place, cases in the rest of Sydney will soon overtake the cases within these 12 LGAs.

Having slowed the growth in the 12 LGAs of concern, it would be devastating if the strong growth in the rest of the state resulted in hospitals being further overloaded and a substantial increase in severe disease and deaths.

It may be necessary to impose greater restrictions — such as curfews and restricting retail outlets such as hardware stores to click-and-collect only — in at least in some of the LGAs with higher growth rates to curb this growth.

Why we need a vaccine-plus strategy

Increased levels of vaccination remains both crucial and urgent to prevent death and severe disease from COVID-19. But we are some way from vaccination levels that can allow us to relax.

Burnet Institute

What does this mean for other parts of Sydney?

The gains associated with the more stringent restrictions are readily reversible. If they are lifted before vaccination can permanently reduce growth, COVID-19 cases could rapidly increase again in these 12 LGAs.

Meanwhile, COVID-19 cases outside the 12 LGAs of concern continue to grow strongly. With the current restrictions in place, cases in the rest of Sydney will soon overtake the cases within these 12 LGAs.

Having slowed the growth in the 12 LGAs of concern, it would be devastating if the strong growth in the rest of the state resulted in hospitals being further overloaded and a substantial increase in severe disease and deaths.

It may be necessary to impose greater restrictions — such as curfews and restricting retail outlets such as hardware stores to click-and-collect only — in at least in some of the LGAs with higher growth rates to curb this growth.

Why we need a vaccine-plus strategy

Increased levels of vaccination remains both crucial and urgent to prevent death and severe disease from COVID-19. But we are some way from vaccination levels that can allow us to relax.

Keeping COVID at may requires vaccination as well as other public health measures.

Joel Carrett/AAP

While the national plan aims for 70% and 80% initial vaccination coverage it’s not yet clear how vaccination levels will impact on case numbers, given we still don’t know how well vaccines reduce transmission of the Delta variant.

Our ability to keep case numbers in check will be highly dependent on the efficiency of ongoing public health measures such as the contact tracing.

Read more:

What is life going to look like once we hit 70% vaccination?

As low case numbers remain a crucial component of a safe exit, “lockdown” restrictions will be important for some time yet to maintain these lower levels in NSW and Victoria.

States and regions that have no community transmission should fiercely protect that status until vaccine levels reach very high levels or else they may also face stringent restrictions.

But lockdowns are clearly not sustainable in the long term. At best, they give health services a temporary breathing space until we get high levels of vaccine coverage.

Keeping COVID at may requires vaccination as well as other public health measures.

Joel Carrett/AAP

While the national plan aims for 70% and 80% initial vaccination coverage it’s not yet clear how vaccination levels will impact on case numbers, given we still don’t know how well vaccines reduce transmission of the Delta variant.

Our ability to keep case numbers in check will be highly dependent on the efficiency of ongoing public health measures such as the contact tracing.

Read more:

What is life going to look like once we hit 70% vaccination?

As low case numbers remain a crucial component of a safe exit, “lockdown” restrictions will be important for some time yet to maintain these lower levels in NSW and Victoria.

States and regions that have no community transmission should fiercely protect that status until vaccine levels reach very high levels or else they may also face stringent restrictions.

But lockdowns are clearly not sustainable in the long term. At best, they give health services a temporary breathing space until we get high levels of vaccine coverage.

Authors: Allan Saul, Senior Principal Research Fellow (Honorary), Burnet Institute