New research shows WA's first governor condoned killing of Noongar people despite proclaiming all equal under law

- Written by Jeremy Martens, Senior Lecturer, History, The University of Western Australia

In June, councillors in Perth’s City of Stirling decided not to change the name of their municipality, despite former Western Australian governor James Stirling’s leading role in the 1834 Pinjarra massacre.

That massacre, in which troops and colonists killed between 15 and 80 Noongar people, is widely known. Less recognised is Stirling’s encouragement of soldiers and settlers to flout the law and employ violence, including murder, against Noongar communities resisting colonial dispossession elsewhere in WA.

Stirling was WA’s first governor from 1829-39. My new research on the early history of pastoralism highlights how this industry’s success was built on the violent conquest of the Avon valley in the 1830s, during which Stirling condoned the unlawful killing of Noongar people by soldiers and settlers.

In one case, for instance, he refused to prosecute a farm worker who killed an Indigenous man in cold blood.

This was despite his proclamation that all the settlement’s inhabitants, Indigenous and European, would be protected equally by British law.

He also argued authorities needed to deliver a decisive blow to “tranquilize” the district. Any balanced assessment of his career in WA should take these actions into account.

‘Liable to be prosecuted’

The proclamation declaring the establishment of Swan River in June 1829 explicitly extended the British legal system to the new settlement.

Indeed Stirling gave notice that if any person was “convicted of behaving in a fraudilent [sic], cruel or felonious Manner towards the Aboriginees of the Country” they would be “liable to be prosecuted and tried for the Offence, as if the same had been committed against any other of His Majesty’s Subjects”.

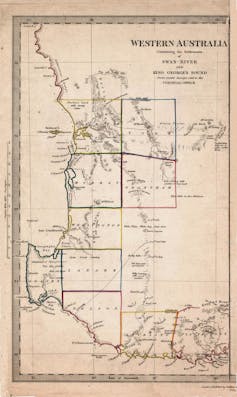

Yet his commitment to abide by the laws he had proclaimed was frequently tested, especially when colonists began to explore and occupy the Avon valley, 60 miles east of Perth. This area became the centre of the colony’s nascent pastoral industry.

Map of WA from the 1830s.

Author provided

Map of WA from the 1830s.

Author provided

The conquest and settlement of the Avon district by pastoralists and farmers in the 1830s was especially bloody. The Noongar people of the Ballardong region, who owned this well-watered and fertile country, bravely resisted the settler incursion.

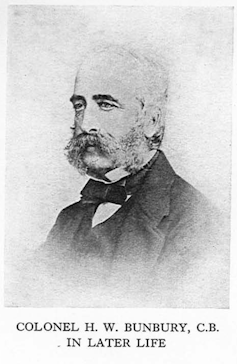

In 1836, Stirling dispatched ten soldiers to the town of York under the command of Lieutenant Henry Bunbury. This young officer (for whom the city of Bunbury south of Perth is named) was instructed by the governor “to take the most decisive measures”. Bunbury took this to mean he had been “ordered over here with a detachment to make war upon the Natives”.

A portrait of Bunbury.

Author provided

A portrait of Bunbury.

Author provided

During 1836 and 1837, Bunbury committed several atrocities, freely admitted to in letters and journals. People sleeping at night were killed without warning. A Noongar man running away from his mounted party was killed, also at night.

Bunbury knew his actions were illegal, but claimed in a letter to Stirling that “severe measures” were necessary. Stirling expressed his satisfaction with Bunbury’s “promptitude”.

In a public notice he explained “a decisive blow” at York was necessary “to tranquilize that District”.

The “boldness” of the Ballardong Noongar resistance meant that nothing would suffice, wrote Stirling, except

an early exhibition of force, or […] such acts of decisive severity, as will appal them as a people for a time, and reduce their tribe to weakness.

Settler killings

Stirling actively condoned the killing of Noongar people by Avon settlers. One particularly egregious atrocity occurred in September 1836 when the pioneering pastoralist Arthur Trimmer ordered a worker to murder a Noongar man “in cool blood”.

The employee, Edward Gallop, was instructed to hide in a barn loft with a gun. The doors of the barn, which contained flour, were intentionally left open and as soon as three men entered to take some, Gallop shot one of them in the head.

Stirling made no public statement condemning this premeditated murder. In a letter to his bosses at the Colonial Office in London, he openly defended settlers’ use of extrajudicial violence.

While expressing his “displeasure and regret at the loss of the Native’s life”, Stirling decided not to prosecute Gallop. He believed that

in cases where the law is necessarily ineffectual for the protection of life and property the right of self protection cannot with justice be circumscribed within very narrow limits.

On several other occasions colonists murdered Noongar people without cause, and in some cases mutilated their bodies. For example, another of Trimmer’s employees named Souper boasted of shooting a woman while hunting in the forest; soldiers under Bunbury’s command later mutilated her body.

When Stirling was asked to investigate and prosecute these crimes by the missionary Louis Giustiniani, he ignored them.

The perpetrators never faced justice.

Authors: Jeremy Martens, Senior Lecturer, History, The University of Western Australia