'Art is our voice': why the government needs to support Indigenous arts, not just sport, in the pandemic

- Written by Angelina Hurley, PhD candidate, Griffith University

This article contains mentions of the Stolen Generations.

The golden rule when organising an arts event with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities is to never hold it at the same time as a sports event. If there is a choice between attending one or the other, chances are our mob are going to that footy game.

Maintaining support for the arts is hard and the COVID pandemic has made it even more difficult. There have been many discussions about the preferential treatment given to sports during the pandemic, while heavy restrictions are applied to arts and cultural events.

While NAIDOC week celebrations were cancelled, the football is still operating. There is annoyance at the complaining commentary about the inconveniences football codes have suffered, not to mention the anger towards the players who don’t follow restrictions.

In the wake of every lockdown, my emails and social media feeds have been flooded with cancellations and closures from local to state theatres, festivals, museums, galleries, residencies, conferences, and workshops. Most temporarily, but some permanent.

Art as voice

Aboriginal art is the first art of this nation, an ancient visual gift of culture and learning. It communicates history, story, and language.

Recently, rock art in the Drysdale River National Park in the Kimberley, the land of the Balanggarra people, has been recognised as “Australia’s oldest-known rock paintings.”

The 17,300-year-old painting of a kangaroo and the 12,000-year-old Gwion figures are breathtaking. They vary in artistic style, identify different social groups, and record ceremony. Rock art is more than just pictorial records, they are historical monuments of Aboriginal culture.

Through our art, the cultural connections of songlines and dreamings continue. Deep principles and concepts are taught through art to tell us the right way to relate to and live with each other. Knowledge is maintained and instructed through art.

Indigenous dancers from WA’s remote Kimberley region standing on the Ngurrara Canvas.

Kimberley Land Council/AAP

Indigenous dancers from WA’s remote Kimberley region standing on the Ngurrara Canvas.

Kimberley Land Council/AAP

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people share histories that are too often ignored. Our art creates spaces for us to remember, mourn, and educate as well as opportunity for social change.

Community Development Worker, Grant Paulson, a Birrah and Bunjalung man, says:

It is important to me to point to something that is a direct reference to me and my culture. It’s nice to see something that is representative of you and your own mob in a world that ignores you most of the time.

Art is our voice. There was none louder in 1996 than the Ngurrara people, who embedded their voice in the creation of an 80 square metre canvas. The beautiful and complex Ngurrara paintings I and II are a depiction of the Walmajarri and Wangkajunga people’s country, the Great Sandy Desert. They are a communal statement of sovereignty.

Created by 19 traditional owners, the paintings are evidence of the Ngurrara people’s connection to country and were submitted as part of their 1996 native title claim. They expressed their rightful claim to land through art.

It was affirming to see as a final declaration each artist stand on the area of the painting they created and speak about the connection they had to country. After ten years, their native title was officially recognised.

Another example of how the selfless nature of Aboriginal people displays itself is through art, and the work of renowned Yankunytjatjara, Pitjantjatjara artist and Ngangkari (traditional doctor) Betty Muffler, which graced the cover of Vogue in September last year for NAIDOC week.

Betty transfers from her hands to the canvas touch, motion, energy, and vibration into her work. For years, this senior cultural woman has walked across country providing healing to areas in need.

A history of silencing Aboriginal art

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have endured ongoing discrimination due to colonisation and settler laws.

Under the guise of stopping the illegal drug trade, the 1897 Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act increased police freedoms. These freedoms included permitting the removal of Aboriginal people from one reserve to another and the removal of Aboriginal children, as well as deciding who these children were to be placed with.

Cultural practices were also banned under the Act, which included no speaking language, no dance, no ceremonies, and no teaching it to their children.

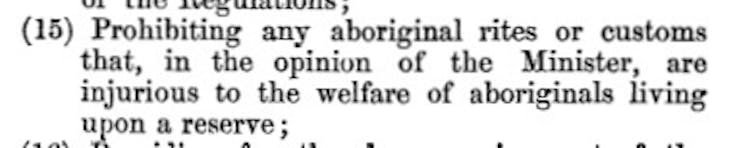

Excerpt from Public Acts of the Parliament of Queensland, The Aboriginals Provision for Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act, 1897.

Author provided, Author provided (no reuse)

Excerpt from Public Acts of the Parliament of Queensland, The Aboriginals Provision for Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act, 1897.

Author provided, Author provided (no reuse)

These laws were enforced up to the mid-1970s. It was an attack on our being, our identity and existence. As a result, intergenerational traumas developed. Removing the practice of art and culture significantly affected the lives of Aboriginal people. The physical and spiritual disconnection from art was detrimental.

Musician Toni Janke, a Wuthathi and Meriam woman, says:

It is about education, responsibility and sharing through communal identity and belonging. It is about passing on our gifts and leaving a legacy for others at a point in time. I believe we are all artists in our own right by virtue of our rich cultural ancestry.

In its modern form, Aboriginal art has allowed for a shared expression of our culture and become world-renowned. Aboriginal culture can be revived through the power of art. As a result of commercialisation, it has become more popular, developing economic sustainability that has enabled some Indigenous people to remain living on Country.

The field of art therapy widely acknowledges and documents the connection between creativity and healing. A creative framework for decolonisation, making art can help combat ailments, reinvigorate and aid emotional well-being. Assertions and expressions of culture reinstate power.

Through visual media, performance, music and the written word, art conveys a story, an experience, a perspective, and an attitude. Sport has even gained from artistic inclusion by putting the designs of First Nations artists on jerseys and merchandise, and through performances at the being of games.

An obvious way to address health and other societal inequalities affecting Aboriginal people is to support their long-standing connection to art and culture.

The government and society as a whole need to prioritise support for the arts during these times — as much as they do for sports.

Authors: Angelina Hurley, PhD candidate, Griffith University