Light and shade: how the natural 'glazes' on the walls of Kimberley rock shelters help reveal the world the artists lived in

- Written by Helen Green, Research Fellow, The University of Melbourne

The Kimberley region is host to Australia’s oldest known rock paintings. But people were carving engravings into some of these rocks before they were creating paintings.

Rock art sites on Balanggarra Country in the northeast Kimberley region are home to numerous such engravings. The oldest paintings are at least 17,300 years old, and the engravings are thought to be even older — but they have so far proved much harder to date accurately.

Cupules, or circular man-made hollows, ground into a dark mineral coating at a rock art site on the Drysdale River, Balanggarra country.

Photo by Damien Finch

Cupules, or circular man-made hollows, ground into a dark mineral coating at a rock art site on the Drysdale River, Balanggarra country.

Photo by Damien Finch

But in research published today in Science Advances, we report on a crucial clue that could help date the engravings, and also reveal what the environment was like for the artists who created them.

Some of the rocks themselves are covered with natural, glaze-like mineral coatings that can help reveal key evidence.

What are these glazes?

These dark, shiny deposits on the surface of the rock are less than a centimetre thick. Yet they have detailed internal structures, featuring alternating light and dark layers of different minerals.

Our aim was to develop methods to reliably date the formation of these coatings and provide age brackets for any associated engravings. However, during this process, we also discovered it is possible to match layers found in samples collected at rock shelters up to 90 kilometres apart.

Radiocarbon dating suggests these layers were deposited around the same time, showing their formation is not specific to particular rock shelters, but controlled by environmental changes on a regional scale.

Dating these deposits can therefore provide reliable age brackets for any associated engravings, while also helping us better understanding the climate and environments in which the artists lived.

Marsupial tracks scratched into a glaze like coating at a rock art shelter in the north east Kimberley.

Photo by Cecilia Myers/Dunkeld Pastoral Company; illustration by Pauline Heaney/Rock Art Australia

Marsupial tracks scratched into a glaze like coating at a rock art shelter in the north east Kimberley.

Photo by Cecilia Myers/Dunkeld Pastoral Company; illustration by Pauline Heaney/Rock Art Australia

Microbes and minerals

Our research supports earlier findings that layers within the glaze structure represent alternating environmental conditions in Kimberley rock shelters, that repeated over thousands of years.

Our model suggests that during drier conditions, bush fires produce ash, which builds up on shelter surfaces. This ash contains a range of minerals, including carbonates and sulphates. We suggest that under the right conditions, these minerals provided nutrients that allowed microbes to live on these shelter surfaces. In the process of digesting these nutrients, the microbes excrete a compound called oxalic acid, which combines with calcium in the ash deposits to form calcium oxalate.

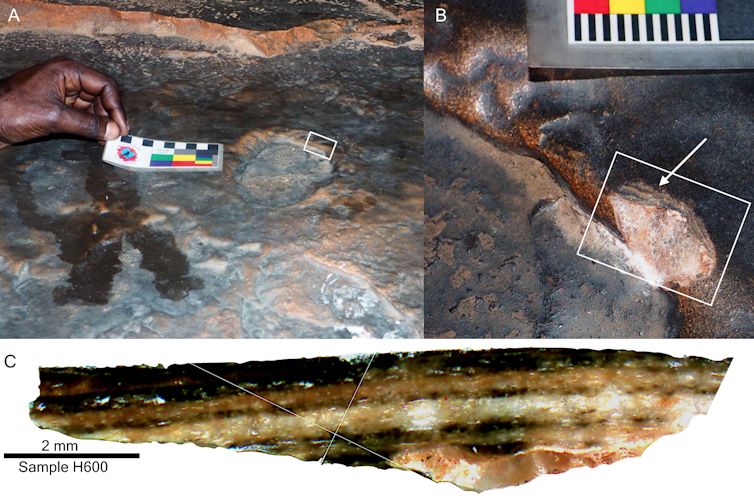

A: dark coloured, smooth mineral coating at a Kimberley rock shelter; B: alternating layering, as seen in the field; C: alternating layering as seen in a cross-sectioned coating under a microscope.

Photos by Cecilia Myers; microscope image by Helen Green

A: dark coloured, smooth mineral coating at a Kimberley rock shelter; B: alternating layering, as seen in the field; C: alternating layering as seen in a cross-sectioned coating under a microscope.

Photos by Cecilia Myers; microscope image by Helen Green

As this process repeats over millennia, the minerals become cemented together in alternating layers, with each layer creating a record of the conditions in the rock shelter at that time.

Samples of the glazes were collected for analysis in close collaboration and consultation with local Traditional Owners from the Balanggarra native title region, who are partners on our research project. Using a laser, we vaporised tiny samples from the coatings to study the chemical composition of each layer. The dark layers were mostly made of calcium oxalate, while lighter layers contained mainly sulphates. We propose darker layers represent a time when microbes were more active and lighter layers represent drier periods.

Read more: How climate change is erasing the world’s oldest rock art

Linking the layers

These dark calcium oxalate layers also contain carbon that was absorbed from the atmosphere and digested by the microbes that created these deposits. This meant we could use a technique called radiocarbon dating to determine the age of these individual layers.

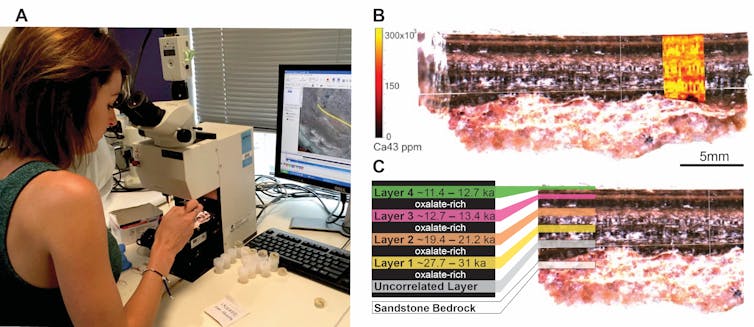

Using a tiny drill, we removed samples from distinct dark layers in nine glazes collected from different rock shelters across the northeast Kimberley.

A: micro-drilling samples from individual layers for radiocarbon dating; B: Laser ablation maps showing the distribution of the element calcium within the different layers; C: radiocarbon dating of individual layers identified four key growth periods.

Photo by Andy Gleadow; illustration by Pauline Heaney

A: micro-drilling samples from individual layers for radiocarbon dating; B: Laser ablation maps showing the distribution of the element calcium within the different layers; C: radiocarbon dating of individual layers identified four key growth periods.

Photo by Andy Gleadow; illustration by Pauline Heaney

Despite coming from different locations, these layers all seem to have been deposited at the same time, during four key intervals spanning the past 43,000 years.

This suggests the formation of each layer was determined mainly by shifts in environmental conditions throughout the Kimberley, rather than by the distinct conditions in each particular rock shelter.

The records held by these glazes over such a large time period - including the most recent ice age - means they could help us better understand the environmental changes that directly affected human habitation and adaptation in Australia.

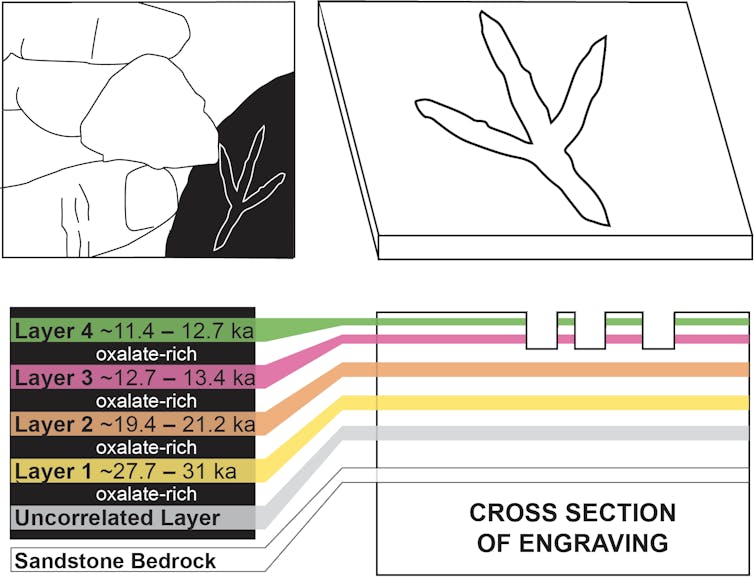

Hypothetical example of how layered mineral coatings can be used to date engraved rock art in Kimberley rock shelters.

Pauline Heaney

Hypothetical example of how layered mineral coatings can be used to date engraved rock art in Kimberley rock shelters.

Pauline Heaney

Stories in stone

Research we published earlier this year shows how the subjects painted in early Kimberley rock art changed from mostly animals and plants around 17,000 years ago, to mostly decorated human figures about 12,000 years ago.

Read more: This 17,500-year-old kangaroo in the Kimberley is Australia's oldest Aboriginal rock painting

Other researchers have discovered that during this 5,000-year period there were rapid rises in sea level, in particular around 14,500 years ago, as well as increased rainfall.

We interpret the change in rock art styles as a response to the social and cultural adaptations triggered by the changing climate and rising sea levels. Paintings of human figures with new technologies such as spear-throwers might show us how people adapted their hunting style to the changing environment and the availability of different types of food.

By dating the natural mineral coatings on the rock surfaces that acted as a canvas for this art, we can hopefully better understand the world in which these artists lived. Not only will this give us more certainty about the position of particular paintings within the overall Kimberley stylistic rock art sequence, but can also tell us about the environments experienced by First Nations people in the Kimberley.

We thank the Balanggarra Aboriginal Corporation, the Centre for Accelerator Science at the Australian National Science and Technology Organisation, Rock Art Australia and Dunkeld Pastoral Co for their collaboration on this research._

Authors: Helen Green, Research Fellow, The University of Melbourne