The Hiroshima Panels are a remarkable artistic exploration of trauma

- Written by Barbara Hartley, Honorary Senior Lecturer, The University of Queensland

On August 6, 1945, the US military obliterated Hiroshima with the world’s first deployed nuclear bomb. Several days later, artist Maruki Iri arrived in his hometown from Tokyo by train. Stunned by the devastation, he felt he was seeing “something that I wasn’t supposed to see”.

Travelling to his family home, the artist negotiated a wasteland, including mounds of dead and barely alive bodies. When his wife, Maruki Toshi, arrived a week later, the pair spent a month assisting bomb blast casualties.

With the end of the war, the Japanese Communist Party saw Allied Occupation forces as liberating Japan and encouraged its followers to focus on a bright future for Japan. Toshi and Iri were party members but struggled to comply. By 1948, each knew they must reproduce in visual art form the perdition they had witnessed.

The pair collaborated on each painting. Iri worked in traditional Nihonga (Japanese painting), although with an idiosyncratic surrealist turn. Toshi’s style was more westernised and featured the human form.

This “water and oil” aesthetic combination produced a spectacularly successful — although sometimes tense — collaboration. Subverting censorship, the Hiroshima Panels (known in Japanese as the Atomic Bomb Panels) were born.

Read more: World politics explainer: The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The Hiroshima Panels

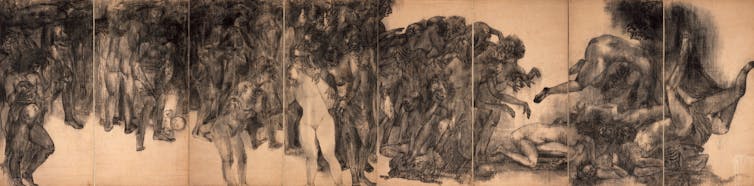

Over three decades, the couple produced 15 Hiroshima-themed panel-scenes, average size 1.8 by 7.2 metres, with accompanying descriptive text.

Each had eight Japanese-screen/scroll style distinct sections. Notwithstanding occasional swirls of colour — vermilion depicting the fires of Hiroshima/Hell — most were the stark black of sumi ink.

The collaboration was not always harmonious. Iri would splash ink over images painstakingly created by his wife. The resultant wash-effect, however, enhanced the impact of bomb-mutilated forms.

Read more: Atomic amnesia: why Hiroshima narratives remain few and far between

Incrementally, the couple’s subject matter expanded to different but similar topics. When an American viewer raised the Japanese Imperial Army’s 1937 Nanjing massacre, the couple produced a 4 by 8 metre image of that atrocity.

They collaborated in this way almost until Iri’s death in 1995.

I Ghosts (幽霊) by Maruki Iri and Maruki Toshi, 1950.

Courtesy the Maruki Gallery

I Ghosts (幽霊) by Maruki Iri and Maruki Toshi, 1950.

Courtesy the Maruki Gallery

The first Hiroshima panel, Ghosts, originally titled August Six, was exhibited in February 1950 at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum when occupation restrictions eased.

Ghosts is a searing depiction of bodies in the post-blast landscape. To the right is a heap of misshapen, ossified corpses, balancing precariously, several faces visible. Left and centre is a massed parade of upright figures, clothes sheared off by the blast, strips of scorched skin dripping from arms instinctively raised as shields.

Seemingly illuminated, the standing body of a woman throws her head back in horror or pain. Perhaps in both.

Depicting the true catastrophe

Initial responses in Japan were mixed. Allied restrictions resulted in limited awareness of Hiroshima’s ordeal, so some thought the work exaggerated. There were survivors who felt the images aestheticised the event. Nevertheless, the Marukis were clearly inspired to continue working on the Hiroshima theme.

One of the few atomic tropes permitted to circulate in the immediate postwar era was the familiar mushroom cloud. This cloud – necessarily distant – elided suffering.

The Marukis, however, depicted the catastrophic scenes beneath.

VII Bamboo Thicket (竹やぶ) by Maruki Iri and Maruki Toshi, 1954.

Courtesy the Maruki Gallery

VII Bamboo Thicket (竹やぶ) by Maruki Iri and Maruki Toshi, 1954.

Courtesy the Maruki Gallery

Several panels profile women with children. One is Bamboo Thicket. Survivors sought shelter in these thickets which often partially survived the explosion. With intertwining body parts and bamboo trunks, the left of the image suggests the catastrophic wind surge generated by the heat of the blast. A woman clasps a child.

Other infants, dead or alive, lie curled up on the ground. A boy – clothes torn away – embraces two younger children. One woman holds up hands charred raw by the thermonuclear heat. The clear visibility of faces makes for particularly disquieting viewing.

Crows depicts Korean victims of the blast, who were often forced labourers in wartime Japan. Deeply discriminated against, Koreans were forsaken by rescuers even in death and their cadaver eyes were pecked out by crows.

While human forms dominate most panels, this work foregrounds the eponymous birds swooping down from the right and eddying above before eventually blanketing the decomposing corpses. In a Marc Chagall-like twist, disembodied traditional Korean women’s attire – the full chima skirt and shaped jeogori coat – float ethereally above the scene.

Art and trauma

Ultra-nationalists in Japan perpetuate a discourse that elides Japanese war atrocity. This can never diminish the unspeakable trauma of the Hiroshima ordeal.

Art undoubtedly has the power to explore trauma. As University of Queensland academics Névine El Nossery and Amy L Hubbell have argued, art transmits trauma’s unspeakability. The power of art, they say, is to “transform and render pain.”

The Maruki Gallery is situated in rural Japan on a rise above the Toki River a little north of Tokyo. Opened in 1967 to make Maruki artwork available to all, the gallery expanded over the decades to include features such as a memorial to Korean people massacred after the 1923 Great Tokyo earthquake.

Read more: Japan's way of remembering World War II still infuriates its neighbours

The extraordinary Hiroshima Panels transform the intense pain of that great crime against humanity into images to be revisited across generations. With Maruki Gallery images now online, people everywhere can contemplate the Hiroshima trauma.

Viewers of the Hiroshima Panels become witnesses to that event. With this witnessing surely comes the need to prevent nuclear war.

A broad complement of Maruki art can be viewed at the Maruki Gallery website.

Authors: Barbara Hartley, Honorary Senior Lecturer, The University of Queensland