The forgotten Australian veterans who opposed National Service and the Vietnam War

- Written by Jon Piccini, Lecturer, Australian Catholic University

On July 26 1971, a top secret cabinet meeting ended what was then Australia’s longest conflict. The public would hear about it for the first time in August, when Prime Minister William McMahon announced the withdrawal of Australian forces from Vietnam.

Eighteen months — and a change of government later — Australia’s Vietnam War was over. Alongside untold Vietnamese, some 521 Australians had died in conflict, including 202 national servicemen.

The end of Australia’s war also saw the wrapping up of a novel and now largely forgotten organisation. The Ex-Services Human Rights Association of Australia was founded in October 1966 by former servicemen and women who “oppose militarism” and “believe that National Service […] should not involve conscription for foreign wars”.

Martin Leslie Waddington, pictured during his World War II service.

Courtesy of the Waddington family, Author provided (no reuse)

Martin Leslie Waddington, pictured during his World War II service.

Courtesy of the Waddington family, Author provided (no reuse)

The final issue of the group’s newsletter, Conscience, in February 1972 paid special tribute to Martin Leslie (Les) Waddington, a World War II veteran and leather goods manufacturer, and the group’s “spiritual leader, and greatest workhorse”.

Fifty years since Australia officially began withdrawing from Vietnam, my forthcoming article reflects on how Waddington exemplified an undercurrent of anti-war citizen soldiery in Australia.

Australia’s anti-militarist tradition

The Ex-Services Human Rights Association of Australia emerged out of a long Australian tradition of opposition to compulsory national service, perhaps best exemplified in the famous struggle against conscription during the first world war.

Pre-war national service schemes had proven unpopular: 27,000 court cases were filed against non-compliers between 1912 and 1914.

During the war, two plebecistes defeated Prime Minister Billy Hughes’ attempts to conscript Australians for overseas service.

Read more: It's time Australia's conscientious objectors of WW1 were remembered, too

This subversive legacy continued. Ex-serviceman and communist Len Fox used a 1936 pamphlet, The Truth About Anzac, to suggest:

[the] heroism of the Conscientious Objector, the Militant Anti-War Fighter, and the Anti-Conscriptionist, [be] give[n] its place besides the heroism of the Anzacs.

While the Menzies government’s National Service scheme of 1964 was initially widely supported as citizen building, the return of “Nashos” in body bags saw the tide of public opinion slowly turn.

From Sydney to a national movement

The Returned and Services League was established in 1916, and by the 1960s the “political pressure group” used its authority to support anti-communism, national service and the Vietnam war.

Waddington was still an active member of his local Cronulla RSL sub-branch when he spearheaded the Ex-Services Human Rights Association of Australia’s founding meeting in 1966.

Attended by both current and former RSL members, and including doctors, academics and “leading lay churchmen”, the Australia reported the 60 attendees were “well-tailored, well-fed and, to all appearances, essentially middle class”.

The Sydney-based group began actively participating in the city’s anti-war movement, including the December 1966 protests against visiting US President Lyndon B Johnson.

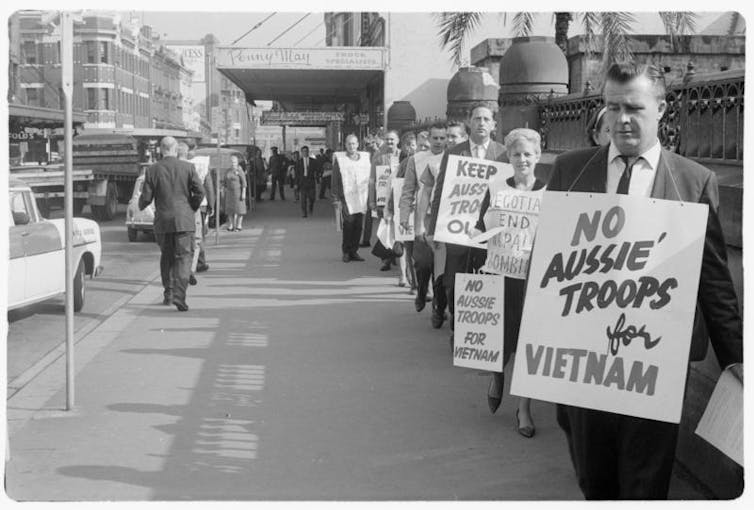

Anti-Vietnam War demonstration outside United States Consulate-General, Sydney, New South Wales, February 1966.

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales and Courtesy SEARCH Foundation, CC BY

Anti-Vietnam War demonstration outside United States Consulate-General, Sydney, New South Wales, February 1966.

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales and Courtesy SEARCH Foundation, CC BY

Waddington believed the Anzac tradition should venerate war resisters as much as battlefield sacrifice. These beliefs saw him expelled by the RSL’s State Executive in late May 1967 for “conduct subversive to the objects and policy of the League”.

The resulting controversy meant “there must be hardly anyone left in this country who has not now heard of our Association”, Waddington happily reported in Conscience. Membership exploded to over 500, with branches across the country.

Fellow RSL members came forward to defend Waddington. One resigned his membership, writing the league displayed “a hardening, intolerant attitude”, while another accused it of “deprivi[ing] members of the right to […] express political opinions”.

An editorial in the Canberra Times stated if the Vietnam war was “the be-all and end-all” of RSL policies, then “there would be great gaps in the ranks”.

Anzac and the heroic resister

Amid the outcry, Waddington was reinstated — but changing the RSL was not the Ex-Services Human Rights Association of Australia’s main priority. Its primary interest was supporting conscientious objectors.

The number of young Australians who refused to serve in Vietnam, while always small, rose quickly after the widely publicised case of Sydney school teacher Bill White in late 1966. The association took on his case, as it did other non-compliers like John Zarb.

Anti-Vietnam War demonstrators protest outside Central Police Court, Liverpool Street, Sydney, 1965.

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales and Courtesy SEARCH Foundation, CC BY

Anti-Vietnam War demonstrators protest outside Central Police Court, Liverpool Street, Sydney, 1965.

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales and Courtesy SEARCH Foundation, CC BY

What the association had — and the wider anti-war movement lacked — was their status as ex-servicepeople. Members wore service medals conspicuously at demonstrations to undermine the image of protesters as “long haired radicals”.

To refuse service was not an act of cowardice, the association claimed, but rather the highest form of bravery. As Waddington, protesting the ongoing imprisonment of objectors, remarked in a 1971 letter:

Two years in jail is the price for national heroes to pay to avoid murdering on a foreign field.

Waddington and his fellow anti-war veterans were convinced it was as brave to face prison for your beliefs as it was to face death on the battlefield.

This example highlights how, contrary to popular opinion, the ex-service community has always been far from monolithic in its politics. Equally, it shows Anzac is not an uncontestable mantra, but a pliable tradition that could, rhetorically at least, include proud soldiers and brave resisters.

Today, Australia reflects on the withdrawal from Vietnam as we face the aftershocks of another overseas war. Perhaps we should also reflect on those war resisters and their allies who believed, as the Ex-Services Human Rights Association of Australia put it, “war is a crime against humanity”.

Read more: Anzac Day is also about the right to democratic dissent and those who fought for it

Authors: Jon Piccini, Lecturer, Australian Catholic University