Decoding the music masterpieces: Liszt's Consolation in D flat — serene sweetness and melancholy

- Written by Stephanie Mccallum, Associate Professor Piano Division, Sydney Conservatorium of Music, University of Sydney

Dreamy, slow-moving and gentle, the D flat Consolation is far from our accepted picture of Liszt, which is often taken from caricatures of his solo recitals: wild hair and eyes, hands flying off the keyboard.

It was written at a crucial turning point for the composer. Liszt’s colourful early life was chronicled, in a one-sided way, by his first mistress, and mother of his three children, Marie d’Agoult, under her nom de plume, Daniel Stern, in a novella later used as a basis for the 1975 film, Lisztomania.

His extraordinary life to this point, breaking class barriers and performing and composing with the status of a superstar, was stranger than fiction. So it is perhaps unsurprising that in mid-life, Liszt took a new direction towards privacy, orchestral conducting and composition. Later, he freely gave of his experience as a teacher to an international audience of young, aspiring pianists.

Born in Hungary in 1811, Liszt developed from being a child prodigy to building a legendary touring career as a virtuoso pianist based in Paris. Still aged in his 30s, internationally famous and revered, he left this behind, settling with his later partner Princess Carolyne Sayn-Wittgenstein, to a quiet life in Weimar in 1848.

Read more: Decoding the music masterpieces: Liszt’s Piano Sonata in B minor

There, he embarked on an incredibly prolific decade of composition. He produced many piano works: both large, like the great B Minor sonata of 1853, and small, like the piece which is our topic today, Consolation No.3 in D flat.

Novelist George Eliot mentions in her letters that Liszt was “the first really inspired man I ever saw.”

She visited him in 1854 and wrote:

Genius, benevolence and tenderness beam from his whole countenance, and his manners are in perfect harmony with it.

A poetic source?

The title, Consolations, was unusual for a suite of piano pieces and is more often connected with poetry. The philosopher and composer Jean-Jaques Rousseau had published a set of songs with chamber accompaniment called Les Consolations in 1781 but otherwise there seems no precedent in music.

Still, poetry and religious contemplation inspired Liszt’s composition Harmonies Poétiques et Religieuses as well as the Consolations. The poetic source for the Consolations may have been an 1830 poetry collection of the same name by Sainte-Beuve. It has also been suggested the title may have the same source as the inspiration for another of Liszt’s pieces, Andante lagrimoso: a poem by Lamartine called A Tear (or Consolation).

We feel that your tender word to others cannot be absorbed, Lord! and that it consoles only those who have otherwise been unconsolable.

One wonders if this poem was in the mind of Kazuo Ishiguro when he wrote his strange, dreamlike novel about a concert pianist, The Unconsoled (1995).

Read more: Decoding the Music Masterpieces: Debussy's Clair de Lune

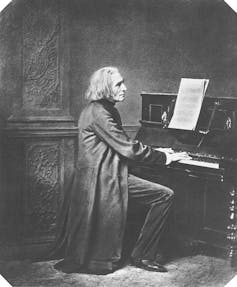

Franz Liszt at the piano, circa 1869.

Wikimedia Commons

Franz Liszt at the piano, circa 1869.

Wikimedia Commons

The six Consolations were composed between 1849 and 1850 and the ten pieces of Harmonies were worked on from 1847 to 1852, the two sets linked by similar expressive content and literary inspiration. Like Beethoven, Liszt reworked and revised constantly.

For his piano compositions, he often simplified or refined their textures. The 1850 Breitkopf & Härtel edition of the Consolations was preceded by an earlier version composed between 1844 and 1849 (published by Henle in 1992). The most famous element of the set, the D flat Consolation No.3 Lento placido (slowly, placidly) was not yet present in the earlier one.

The six pieces of the Consolations sandwich two D flat major pieces between pairs of pieces in E major:

- Andante con moto in E major

- Un poco più mosso in E major

- Lento placido in D♭ major

- Quasi Adagio in D♭ major (based on a theme by the Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna of Weimar).

- Andantino in E major

- Allegretto sempre cantabile in E major

After Chopin’s death in 1849 Liszt worked on a book about him over several years. This preoccupation spilled over into his writing several piano pieces with similar titles to Chopin though all of them were in Liszt’s individual style.

Chopin was famous for his Nocturnes and it has often been noted that in Liszt’s D flat Consolation No.3, the opening texture and first singing note, as well as the key, recall Chopin’s Nocturne Op 27 No.2.

Its composition coincides with Chopin’s death so, consciously or subconsciously, it is possibly a tribute to him.

Song-like narrative

Liszt’s Consolation No.3 opens with repeating, long, low D flats held in the pedal. More than 20 years later, Steinway piano manufacturers presented Liszt with a new piano with a third or middle pedal (or sostenuto) capable of allowing one or more strings to vibrate while other strings were stopped from vibrating by the damper mechanism. (Dampers bring down a piece of felt on the string.)

Liszt noted that this pedal could assist in the opening bars and peaceful passages of this piece. He wrote in 1883:

In relation to the use of your welcome tone-sustaining pedal I inclose (sic) two examples: Danse des Sylphes, by Berlioz, and No. 3 of my Consolations. I have today noted down only the introductory bars of both pieces, with this proviso, that, if you desire it, I shall gladly complete the whole transcription, with exact adaptation of your tone-sustaining pedal.

One of Liszt’s pianos.

Wikimedia Commons

One of Liszt’s pianos.

Wikimedia Commons

The piece however was certainly composed with the normal two pedals in mind. Both would be applied in the opening, marked pianississimo (as soft as possible) and sempre legatissimo (always as smoothly linked as possible).

For the pianist, as harmonies change above the low D flat, it is necessary to silently retake the low note as the pedal is changed, or else try a “half pedal” where lower reverberative notes survive a partial manipulation of the pedal while light upper notes do not.

This type of pedal use is necessary in much of Liszt’s piano writing where many decorative notes are spun above a low, pedal-held bass note. The indication, cantando (singing), in the third bar marks the beginning of the eloquent solo line or songlike narrative.

One of the charming characteristics here is the way each phrase fades out with an ornamental upward broken chord. While the accompanying harmonies are in groups of three notes (or triplets), the melodic line uses groups of two and sometimes four notes in each beat, giving a freely fluid quality, independent of the accompaniment.

When the lower accompanying harmonies sometimes briefly cease, the melody is left alone, creating an expressive soliloquy that seems to be almost speaking rather than singing.

The texture then changes to the lightness of the higher register of the piano and the phrase endings reach further upwards creating more complex patterns of rhythm.

The long bass notes shift, taking us to a new, more melancholy key.

With our new key, the texture is louder, enriched with more notes, and gives a series of magical alternations between serene sweetness and melancholy.

A final crescendo leads us to a strong return of our opening with its long D flat bass note.

We now hear the opening melody again but subtly transformed, lower down the keyboard.

An ethereal moment is captured by an unexpected chord which sparks a floating shimmer of notes. As quietly as we began, we depart and are left suspended, freely descending.

The enigmatic quality of this final gesture contributes to our sense of having glimpsed a fleeting, special moment.

This beautiful and sophisticated work is well within reach of the amateur pianist. Its simplicity of structure, along with the charm and depth of its musical thoughts have made it a well-loved and enduring piece in piano repertoire.

Authors: Stephanie Mccallum, Associate Professor Piano Division, Sydney Conservatorium of Music, University of Sydney