Friday essay: rethinking the myth of Daphne, a woman who chooses eternal silence over sexual assault

- Written by Marguerite Johnson, Professor of Classics, University of Newcastle

Ancient Greek myths and folktales are shaping popular culture, from big-budget films to television series to novels. You can even find advice on how to look like a Greek goddess or heroine on your wedding day, with gowns inspired by Aphrodite and Helen of Troy (among others).

In particular, myths of transformation have appeal to artists and writers who are attracted to the challenge of retelling stories of shifting forms — the strange movements between human and animal or plant. Such states of flux can shed light on our own understanding of identity.

Among the many mythical figures changed through metamorphosis is the nymph or dryad, Daphne. One of the mythical beings who cared for trees, springs and other natural elements, Daphne was the child of Peneus, a Thessalian river god.

Her decidedly sad and violent story, in which she is transformed into a tree to escape the lustful attention of the god Apollo, gives rise to the ancient explanation of the creation of the laurel tree, known as “daphne” by the ancient Greeks.

Daphne’s plight continues to intrigue artists. Today, new interpretations are finding fresh ways of reading this influential, much contested myth, with its themes of sexual violence and bodily autonomy.

Andrea Schiavone, Apollo and Daphne, 1542.

Wikimedia Commons

Andrea Schiavone, Apollo and Daphne, 1542.

Wikimedia Commons

Parthenius (1st Century BCE-1st Century CE) provides the earliest complete extant version of the myth of Daphne and Apollo. As a grammarian, Parthenius collected stories from texts now lost to us. Still, his version of the story can be traced to earlier works dating to the 3rd century BCE, suggesting the myth is even older.

Parthenius’ version begins with Leucippus, the son of a mythic king of Pisa, falling in love with the beautiful nymph. Daphne was favoured by the goddess Artemis, who bestowed upon her the gift of shooting a straight arrow. Leucippus contrived to spend time with Daphne by dressing as a woman and joining her during a hunt.

But this enraged Apollo, who also desired Daphne. He encouraged Daphne and her fellow female hunters to bathe in a nearby stream. When Leucippus refused to join them, the women stripped him, discovering his ruse and stabbing him with their spears.

but Daphne, seeing Apollo advancing upon her, took vigorously to flight; then, as he pursued her, she implored Zeus that she might be translated away from mortal sight, and she is supposed to have become the bay tree which is called daphne after her.

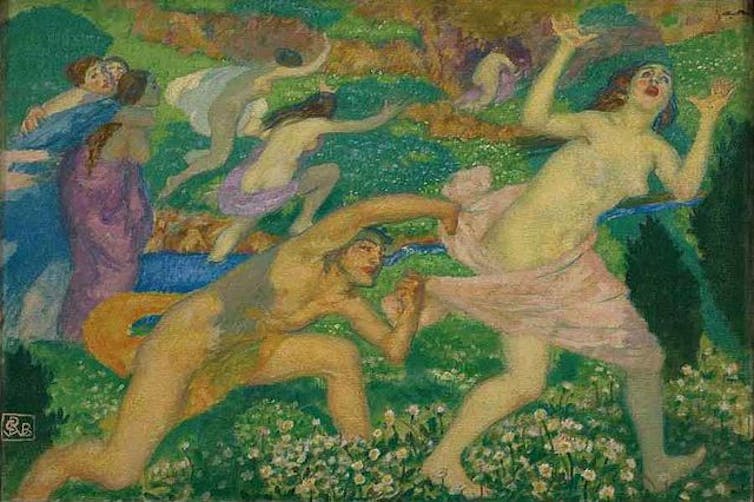

Apollo and Daphne by Rupert Bunny, early 1920s.

Wikimedia Commons

Apollo and Daphne by Rupert Bunny, early 1920s.

Wikimedia Commons

‘Destroy this beautiful figure’

The Latin poet, Ovid (43 BCE-17 CE) retells Daphne’s story in Book 1 of his epic poem of transformation myths, the Metamorphoses. Ovid explains that Apollo’s desire was caused by Cupid, whom Apollo had slighted. In response, Cupid shot Apollo, causing him to feel intense passion for Daphne. But she was shot with another type of arrow, ensuring she would not reciprocate his attraction.

Read more: Guide to the classics: Ovid's Metamorphoses and reading rape

Ovid’s version depicts a frightened Daphne fleeing her pursuer with language that paints her as a hare hunted by a greyhound. Daphne’s fear of being caught by Apollo as he chases her is evoked with visceral realism. Her transformation comes when she no longer has the strength to run:

With her strength used up, she went pale with fear and, overcome by the effort of her frantic flight and gazing upon the waters of Peneus, she cried: ‘bring help, father, if your waters possess divine power! By changing it, destroy this beautiful figure by which I generated too much desire.’

With her prayer scarcely completed, a heavy torpor took possession of her limbs: her soft breasts were bound by a thin layer of bark, her hair grew into foliage, her arms into branches; her feet, just now so swift, hold fast in sluggish roots, a crest possessed her facial features, radiance alone remained in her.

Even without human form, Daphne is not saved from Apollo’s lust. After her transformation, Apollo reaches out to touch the trunk of the tree, which shrinks from him.

In the final lines of this episode, Ovid reveals what Apollo does with this tree’s leaves: they are woven into a laurel wreath and around his quiver and lyre, to be used in rituals performed in his honour.

While Daphne is saved from the assault of her human form, she is nonetheless forcibly objectified for the sake of Apollo’s desire.

Loss of self

Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne.

Wikimedia Commons

Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne.

Wikimedia Commons

Since antiquity, the story of Daphne has been retold over and over again – painted, sculpted, performed and analysed.

We can gaze at Daphne in all manner of poses in museums and galleries throughout Europe. The Galleria Borghese in Rome displays Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s Daphne being seized by Apollo in a life-size, marble statue.

Completed in 1625, it depicts Apollo’s intense determination as he seizes the nymph by the waist with one hand even though she is in the very process of turning into a tree.

While his face is eerily peaceful, Daphne’s replicates the fear that underscores Ovid’s description.

In this way, Bernini’s sculpture is Ovid’s poetry in material form. Masterpieces of art and literature, respectively, compromise us by the beauty that depicts a narrative of attempted rape.

A rear view of the Bernini sculpture.

Eva Petrilllo/Shutterstock

A rear view of the Bernini sculpture.

Eva Petrilllo/Shutterstock

The Louvre has Giambattista Tiepolo’s version of the myth, dating to approximately 1774. Here, a baby Cupid hoists Daphne as if she were a ballerina while Apollo seems somewhat discombobulated. An aged Peneus slumps on the ground, seemingly exhausted from his transformative magic.

While Bernini’s Daphne is shocked and traumatised, Tiepolo’s nymph — with her attendant narrative of fear and suffering — has been tamed for a genteel Baroque audience. This silly and passive rendition of sexual assault is accentuated by the delicate shoots of foliage that grow from Daphne’s right hand.

Giambattista Tiepolo, Apollo and Daphne, circa 1774.

Giambattista Tiepolo, Apollo and Daphne, circa 1774.

Historically, scholarship has shown a deep-seated patriarchal interpretation of the myth, rendering Daphne’s role in her own transformation as secondary to the actions of masculine power, represented by Apollo.

The creation of the laurel wreath, for instance, recorded by Ovid, has been interpreted as an act of mourning, turning Daphne’s transformed body into a symbol of Apollo’s grief.

Feminist interpretations, however, remind us Apollo’s intention was to rape Daphne. Thus his grief was firmly based on his failed attempt and nothing more. These interpretations encourage us to consider the intense violence inherent in the myth.

As a tree, leafy and earth-bound, Daphne’s loss of self is both physical and psychological. No longer human, she loses the ability to express herself through her facial features, and the power of speech. Like so many women in the myths of transformation, Daphne is perpetually silenced. She can only “speak” through the rustling of leaves.

The burden of women’s historic experience of sexual harassment, violation and rape is also vividly chronicled in Daphne’s story. Ovid, a master of narratives of violence and abuse, reveals Daphne’s burden by suggesting she sees herself as partly accountable for Apollo’s pursuit of her. In her prayer to her father, she begs to be relieved of her beauty, which she believes has caused the god’s actions.

Her pleas have echoed across millennia in the self-admonishment of many women and their desire to become invisible to the male gaze. Daphne achieves a form of invisibility — or so she thinks — in her new form as a mass of leaves and bark. But, as Ovid tells us, not even as a tree can she escape the god’s persistent lust.

The sheer absurdity of the entire myth begs the question: would a woman prefer to become a tree than be raped?

Modern interpretations

In the 20th century, Salvador Dalí, Paul Delvaux and Ossip Zadkine all reworked Daphne; painting and sculpting her for a modernist audience.

Zadkine’s sculpture, Daphné (1958) mirrors yet mocks Bernini’s work, rendering the nymph as a powerful root-bound tree of monumental grandeur and ungainly defiance. She, however, remains silent.

In a new exhibition opening at Melbourne’s Australian Centre of Contemporary Art, Australian audiences can see some of Daphne’s incarnations over the centuries, including early works, such as Anthonie Waterloo’s etching of Apollo and Daphne (1650s) and Agostino dei Musi’s engraving from 1515.

Agostino dei Musi, Apollo and Daphne 1515, engraving, 23.0 x 17.0 cm. Art Gallery of New South Wales, purchased 1937.

Photograph: AGNSW

Agostino dei Musi, Apollo and Daphne 1515, engraving, 23.0 x 17.0 cm. Art Gallery of New South Wales, purchased 1937.

Photograph: AGNSW

Traditional works celebrating the so-called grandeur of classical mythology so much in vogue in the Renaissance (and beyond) are joined and contested by competing interpretations. These include Erik Bünger’s Nature see you (2021), a video essay on the world-famous but inherently vulnerable gorilla, Koko; and Ho Tzu Nyen’s 2 or 3 Tigers (2015), a digital projection that meditates on tigers in the Malay context.

In both works, we see the story of Daphne as sentient nature in the form of gorilla and tiger, and nature both mythical and metaphorical. We also see nature as silent and therefore fragile in a world of human gods who are just as ruthless and destructive as their mythical counterparts.

Ho Tzu Nyen, 2 or 3 Tigers 2015 (video still), synchronized two-channel HD projection, 12 channel sound, 18:46 mins.

Courtesy the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong

Ho Tzu Nyen, 2 or 3 Tigers 2015 (video still), synchronized two-channel HD projection, 12 channel sound, 18:46 mins.

Courtesy the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong

Daphne’s humanity — her womanhood — is also referenced in Wingu Tingima’s paint on canvas, Kawun (2005). Based on the traditional Indigenous Australian story of the Seven Sisters, Tingima’s work suggests the trauma of women as they travel to escape the desires of the Ancestral Being Nyiru, who is determined to take one of them as his wife.

Read more: Songlines: Tracking the Seven Sisters is a must-visit exhibition for all Australians

Like Daphne, the sisters escape by ascending to the sky and transforming into the constellation known as the Pleiades.

This rich exhibition approaches the myth of Daphne from many angles. Working back and forth through time, mixing traditional ways of seeing with vital contemporary narratives (including the Anthropocene, #MeToo, and post-humanism), it is an uncomfortable reminder of the power of myth and its own vulnerability to the forces of transformation.

A Biography of Daphne opens at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art in Melbourne on June 26 and runs to September 5 2021.

Authors: Marguerite Johnson, Professor of Classics, University of Newcastle