Guide to the Classics: Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, a tragicomedy for our times

- Written by Mark Byron, Senior Lecturer, Department of English, University of Sydney

Vladimir: Well? Shall we go?

Estragon: Yes, let’s go.

[They do not move.]

Samuel Beckett originally subtitled his 1953 play Waiting for Godot “a tragicomedy in two acts”. Vivian Mercier, the critic for the Irish Times, dubbed it “a play in which nothing happens, twice.”

Two tramps, Vladimir and Estragon, wait on the side of a country road. Each act begins with the pair reunited after spending the night apart. As they await their enigmatic patron, Godot, Estragon laments being beaten by nameless figures during the night, and Vladimir seeks to pass the time by stirring his companion into repartee.

These two are ill-starred but well-suited: Estragon’s feet are in constant pain, and Vladimir’s unspecified affliction induces frequent and painful urination. Estragon’s shoes stink, while Vladimir adheres to a diet of garlic to ease the symptoms of his condition. Vladimir remembers, and Estragon forgets.

Memory stretches into the deep past. The present sits on the cusp of a hopeful future. Time’s recurrence is marked by the moon and the sun. The endless wait for a rendezvous … for what, exactly?

To receive instructions? To be delivered from this tormented life? To relieve the tramps of their little canters, their bombastic declarations, their pleas? To relieve the steadfast audience?

From its first performances in the 1950s, Waiting for Godot enjoyed a positive critical reception. Yet its earliest audiences thought otherwise, ensuring the interval was the most popular part of the play by voting with their feet. Over time, though, Godot would become a celebrated avant-garde play, and a popular cultural reference for fruitless waiting.

This waiting is eerily prescient in a time of pandemic.

From Dublin to Paris

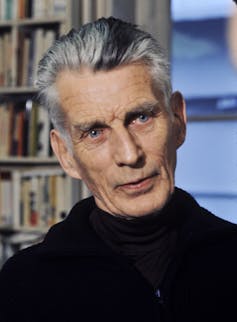

Samuel Beckett photographed in 1977.

Wikimedia Commons

Samuel Beckett photographed in 1977.

Wikimedia Commons

Samuel Beckett was born in Dublin in 1906. As a child he boarded at the Portora Royal School in Enniskillen (Oscar Wilde’s alma mater), before a degree in Modern Languages and Literature at Trinity College Dublin.

His enduring relation with Paris began soon after. During his two-year position as lecteur d'anglais at the Ecole Normale Superiéure (1928-29) Beckett met and became close with James Joyce, who introduced him to the Parisian literary and artistic avant-garde.

Beckett spent two years in London (1933-35) undergoing a course of psychoanalysis under Walter Bion at the Tavistock Clinic, during which he wrote his first published novel, Murphy (1938). Following travels in Germany and Italy, Beckett settled in Paris in 1938, as war looked increasingly likely.

Beckett joined the French Resistance but his cell was infiltrated and he was forced to flee to Roussillon for the duration of the war, where he composed the novel Watt (published in 1953) in English. Back in Paris, Beckett embraced French and embarked upon one of modern literature’s most eccentric and fruitful monastic episodes: the “siege in the room” which yielded the trilogy Molloy (1951), Malone Dies (1953) and The Unnamable (1953).

The script opens with the stage directions ‘A country road. A tree. Evening.’, as in this New Orleans street art.

Derek Bridges/flickr, CC BY-NC-SA

The script opens with the stage directions ‘A country road. A tree. Evening.’, as in this New Orleans street art.

Derek Bridges/flickr, CC BY-NC-SA

Beckett’s trilogy contributed to the new wave of French postwar novels renowned for their spare style and forensic treatment of plot, a movement that came to be known as the nouveau roman (“New Novel”).

Beckett wrote Waiting for Godot between October 1948 and January 1949. It was his first play to reach the stage — his first full playscript, Eleuthéria, was written in 1947 but only published posthumously.

Nothing, twice

Despite appearances, Godot is a surprising blend of suspense and dramatic action. Themes repeat over both acts: the same waiting, the same fights. A messenger boy appears in each act — or, perhaps, two different boys in each act, brothers. The horizon of time is scanned twice, once in each act.

The symmetry of Vladimir and Estragon, endlessly waiting for the unseen Godot, is echoed by another pair, Pozzo and Lucky, who pass by in each act. In Act 1, Pozzo is the grand landlord — a revenant of the Irish Big House literary tradition — whipping his servant Lucky into service.

Pozzo’s pomposity is matched by Lucky’s silence, and when Pozzo compels Lucky to speak, finally, Lucky’s cascade of logorrhea stands in contrast to Pozzo’s grandiloquence.

The symmetry of Estragon and Vladimir is contrasted in the grand Pozzo (here played by Philip Quast) and the meek Lucky (here played by Luke Mullins).

AAP Image/Sydney Theatre Company, Lisa Tomasetti

The symmetry of Estragon and Vladimir is contrasted in the grand Pozzo (here played by Philip Quast) and the meek Lucky (here played by Luke Mullins).

AAP Image/Sydney Theatre Company, Lisa Tomasetti

In Act 2 Pozzo returns, blinded, his authority diminished to the merely rhetorical. His final speech echoes Macbeth on time and the brevity of life. In Shakespeare’s play, Macbeth pronounces:

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player / That struts and frets his hour upon the stage / And then is heard no more

Pozzo’s final passionate outburst reduces life to:

the same day, the same second […] They give birth astride the grave, the light gleams an instant, then it’s night once more.

Estragon’s complete indifference to Pozzo’s swansong has Vladimir wonder at his own dilemma, inducing an irrevocable moment of clear vision:

At me too someone is looking, of me too someone is saying, he is sleeping, he knows nothing, let him sleep on.

This burden of recognition places Valdimir within a tragic mode, out of step with the farcical tragicomedy around him. He is no longer immersed in the condition of waiting, but breaks through to understand the act of waiting as a condition of life.

Audible yawns – from those who stayed

Godot premièred at the Théâtre du Babylone in Paris in January 1953. The play drew positive attention from reviewers and from some of the biggest names in French theatre and literature. Its fame rose slowly — then abruptly, when a fistfight broke out in the interval of one performance, between the play’s defenders and those offended or shocked by its (in)action and the cruel plight of the character Lucky.

Its English-language premiere in London in August 1955 was met with “waves of hostility” and audible yawning from audience members who remained after interval.

The play’s fate in the United States was little short of catastrophic: billed as “the laugh sensation of two continents”, its opening night in January 1956 at the Coconut Grove Playhouse in Miami was farcical.

Even Alan Schneider’s expert direction couldn’t salvage the play from a disruptive rehearsal atmosphere, complicated sets and an ill-suited venue. The interval, again, turned out to be the most popular part of the performance.

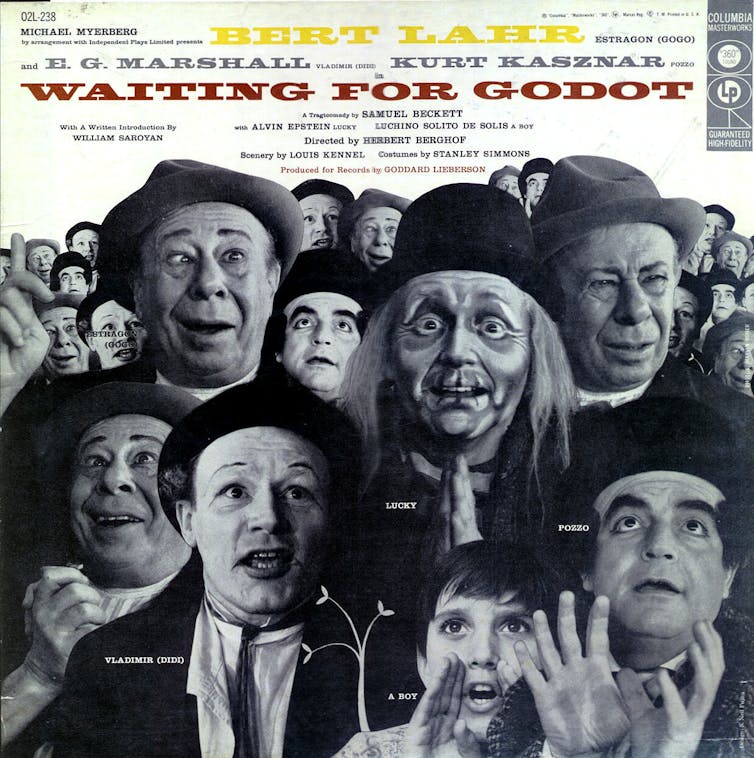

Bert Lahr (who played the Lion in 1939’s The Wizard of Oz) played Estragon in Miami and would be instrumental in the play’s success later that year on Broadway, an event that remained one of his career highlights.

Waiting for Godot played on Broadway for only 10 weeks, but Bert Lahr’s performance was immortalised by Columbia Records.

Internet Archive

Waiting for Godot played on Broadway for only 10 weeks, but Bert Lahr’s performance was immortalised by Columbia Records.

Internet Archive

During those early years, Godot was also performed in prisons, including a landmark production by the San Francisco Actors Workshop at San Quentin State Prison in 1957. Inmates were astounded a playwright could capture limbo with such insight and sensitivity.

All of us are waiting

Over time its fame has grown to the point where Godot is a definitive meeting point of the avant-garde and popular culture. The play has inspired numerous parodies and spin-offs, perhaps most notably the 1996 mockumentary Waiting for Guffman, in which the cast of a small-town musical production in Missouri awaits the arrival of a legendary Broadway producer.

The claustrophobia of Beckett’s next play, Endgame (1957), might capture the experience of lockdown in the current pandemic (“Beyond [the wall] is the other hell”), but Godot captures the distortions of time combined with the uncertainty of respite.

Populations across the globe have endured various kinds of waiting: waiting for published infection numbers, for hospital beds, for oxygen supplies, for borders to reopen, for opportunities to see loved ones. Running through our individual narratives, waiting has proved to be a truly global, shared experience.

How do we remember pre-pandemic times – that past “a million years ago,” as Vladimir pronounces in the play – and what do we forget?

Estragon exclaims: “Nothing happens. Nobody comes, nobody goes. It’s awful.” But dilatory time and static place also offer opportunities for new perception: a long moment to consider our circumstances and ourselves anew.

Authors: Mark Byron, Senior Lecturer, Department of English, University of Sydney