Vaping and e-cigarettes are glamourised on social media, putting young people in harm's way

- Written by Jonine Jancey, Academic and Director Collaboration for Evidence, Research and Impact in Public Health, Curtin University

Despite their widespread reputation as a “safer” alternative to cigarettes, e-cigarettes (also known as electronic cigarettes or vapes) are far from harmless, particularly for adolescents, whose developing brains may suffer lifelong adverse effects from nicotine-containing products.

Yet vaping and e-cigarettes are widely promoted on social media by the industry and influencers, using advertising tactics that were outlawed for tobacco in Australia in the 1980s for traditional media. This blatant promotion is not tolerated offline, so why is it happening on social media?

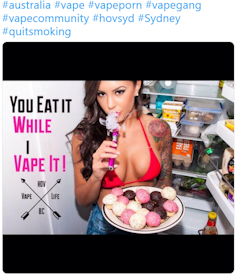

Twitter image.

Twitter image.

On Twitter, YouTube and Instagram, e-cigarettes are frequently depicted as a safe and healthy alternative to cigarettes. This is at odds with the opinion of health authorities such as the Office of the Surgeon General, the Federal Health Department and the World Health Organization (WHO). There is substantial evidence e-cigarettes have adverse health effects but because they are relatively new (they were first introduced to the US market in 2007) their long-term effects are less clear.

Yet e-cigarettes are touted online as a harmless recreational activity. Vape juice (which may or may not contain nicotine) is available in flavours such as gummy bear, chocolate treat and cherry crush, while social media influencers demonstrate fun vaping tricks or ways to customise e-cigarette devices. There are even online vaping communities offering social support and connectedness.

There is no Australian federal legislation that directly applies to e-cigarettes. Instead, several laws relating to poisons, therapeutic goods and tobacco apply. Across Australian states and territories, it is illegal to sell nicotine-containing e-cigarettes but users can legally import them through a “personal importation scheme” if they have a doctor’s prescription.

Those that do not contain nicotine can be sold in some parts of Australia, provided there are no therapeutic claims. Our research found that despite Australia’s restrictions, the internet is facilitating peoples’ access to nicotine and vaping products. An estimated three-quarters of e-cigarette purchases are done online.

To find this content, all you need is a smart phone and a few relevant hashtags such as product names, or related terms such as: #vape, #vapelife, #vapesale and #ejuice.

Images from Instagram, Twitter and TikTok display a mixture of modern advertising techniques and advertising tropes used for decades by the tobacco industry. There are images of scantily dressed women with e-cigarettes, details of tempting vape juice flavours, and discount offers. The scope of this content is alarming.

Old-school advertising tactics on Twitter.

Old-school advertising tactics on Twitter.

This promotion, coupled with the product diversity and allure, ease of online purchase and lack of appropriate age verification, supports the growth of e-cigarettes, particularly among young people. Young people are the biggest users of social media, and they are being directly targeted.

E-cigarette use has been described as an “epidemic among youth”. In Australia, since 2013, the lifetime use of e-cigarettes has significantly increased — doubling in 14-17 year olds (4.3% to 9.6%) and almost tripling in those aged 18-24 (7.9% to 26.1%), while rates of cigarette smoking have declined.

This increased e-cigarette uptake by young Australians is particularly worrying. While promotion and advertising of this product are tightly regulated offline, with age restrictions that are relatively easy to enforce, posing as an adult online is often simply a matter of ticking a box.

Despite the dangers of e-cigarettes, many adolescents have positive opinions about them. Surveys have revealed young people consider e-cigarettes to be a healthier and less addictive alternative to cigarettes, with fewer harmful chemicals and fewer health risks from second-hand vapour.

Tobacco companies have a tradition of infiltrating youth-friendly media. Almost all Australians aged between 18 and 29 use social media, for more than 100 minutes a day on average. The high visibility of e-cigarettes available on social media can foster awareness, encourage experimentation and uptake, and change social norms around vaping.

Social media platforms do have their own policies on tobacco advertising. Facebook and its subsidiary Instagram stipulate:

Advertisements must not promote electronic cigarettes, vaporizers, or any other products that simulate smoking.

This policy has now been extended to all private sales, trades, transfers or gifting of tobacco products. Any brand that posts content related to the sale or transfer of these products must restrict it to adults 18 years or older. Whether this is even possible on social media is still open to question.

Twitter image promotion.

Twitter image promotion.

Twitter’s policy on paid advertising “prohibits the promotion of tobacco products, accessories and brands globally”. But this does not extend to the content of individual accounts.

TikTok’s advertising policy states:

Ad creatives and landing page must not display or promote tobacco, tobacco-related products such as cigars, tobacco pipes, rolling papers, or e-cigarettes.

Vape juice advertising on TikTok.

Vape juice advertising on TikTok.

But on social media, where “influencer” content is king, the boundaries between truly organic content and paid product placements is blurred.

In 2012, Australia tried to counter this emerging online situation by introducing legislation making it an offence to advertise or promote tobacco products on the internet, unless compliant with existing advertising laws. But that legislation doesn’t ban online sales of tobacco products, including vaping products, and can do very little about advertisements from overseas websites.

It is unclear whether health authorities and regulators are aware of the scale and explicitness of e-cigarette content on social media. It seems clear that more should be done to counter it.

Australia, along with close to 170 other countries, is a signatory to the WHO’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control , which calls on nations to outlaw all advertising for tobacco products, including e-cigarettes.

Action is required. Australia, and other nations from which this content originates, need to prioritise public health. There needs to be improved surveillance, monitoring and the curtailing of content that glamourises e-cigarettes, as well as improved age verification practices.

Authors: Jonine Jancey, Academic and Director Collaboration for Evidence, Research and Impact in Public Health, Curtin University