Crime is rife on farms, yet reporting remains stubbornly low. Here's how new initiatives are making progress

- Written by Kyle J.D. Mulrooney, Senior Lecturer in Criminology, Co-director of the Centre for Rural Criminology, University of New England

Crime on farms can have devastating effects on farmers and their families —financial, psychological and social. Crime can also have national implications, too, if it disrupts or damages farm production.

But too often, farm crime is considered “just a rural issue”, something out of sight and mind.

This is why the Centre for Rural Criminology at the University of New England launched a crime survey of farmers last year in New South Wales. We wanted to gain a better understanding of the often hidden dimensions of crime in rural areas to inform decision-making by government, police, farmers and other organisations.

High rates of farmer victimisation

In our survey, the most jarring finding was just how prevalent crimes in rural areas is. Four in five farmers (80.8%) reported having been a victim of some type of farm crime.

Repeat victimisation is high, too: three in four farmers (76.8%) reported being a victim of crime on two or more occasions, and almost a quarter (23.3%) experienced crime a staggering seven times or more.

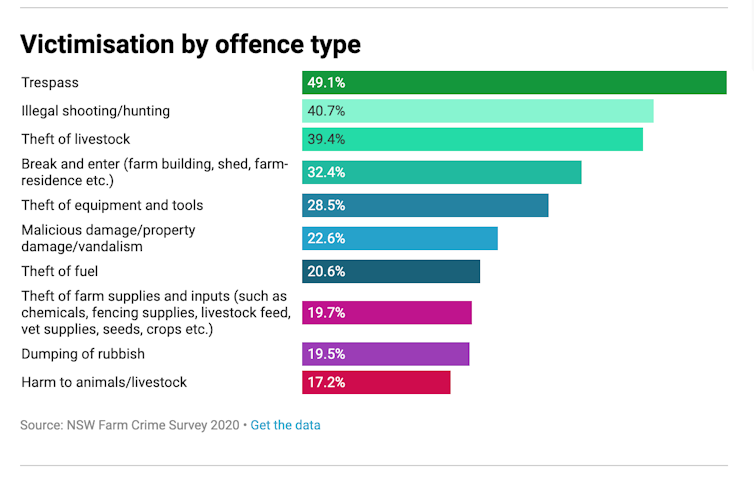

The most common type of crime reported by our survey respondents was trespassing on their property (49.9%). Illegal shooting and hunting (40.7%), theft of livestock (39.4%), and break and enter of farm properties (32.4%) were also high on the list.

A reluctance by farmers to report crime

Despite these significant levels of victimisation, farmers are often reluctant to report farm crime to police. Only two-thirds (66.7%) of victims reported stock theft to police, for example. And trespassing and illegal shooting and hunting were reported by farmers less than half the time.

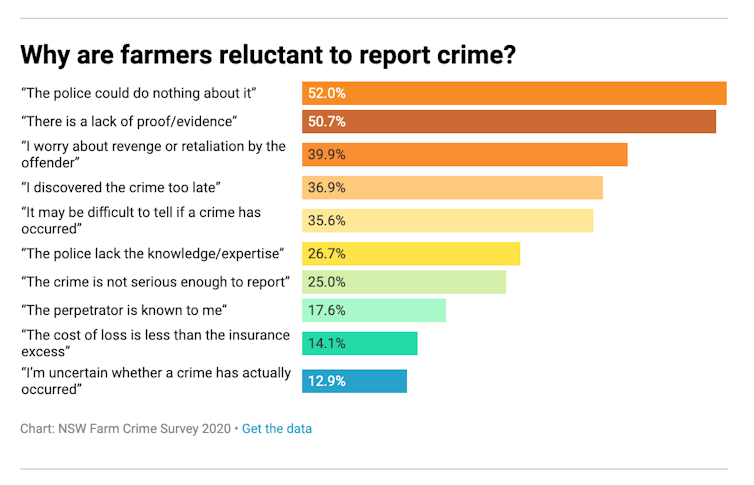

Reluctance to report crimes is linked primarily to a lack of confidence in police interest and capacity to solve them if they are reported, as well as perceptions of barriers to investigating crimes in rural areas.

A reluctance by farmers to report crime

Despite these significant levels of victimisation, farmers are often reluctant to report farm crime to police. Only two-thirds (66.7%) of victims reported stock theft to police, for example. And trespassing and illegal shooting and hunting were reported by farmers less than half the time.

Reluctance to report crimes is linked primarily to a lack of confidence in police interest and capacity to solve them if they are reported, as well as perceptions of barriers to investigating crimes in rural areas.

Other reasons for non-reporting include a belief that a crime is not serious enough to report or concerns about revenge in a small community (nearly 40%).

This “dark figure of crime” — the term used to describe the number of committed crimes that are not reported or discovered — not only means the weight of the law won’t be applied to those who engage in criminality, but that policy-makers are unaware of the true extent of rural offending rates and patterns.

The effects of farm crime

Farm crime is costly. Let’s consider stock theft. NSW police figures indicate that between 2015 and 2020, an average of 1,800 cattle and 16,700 sheep were stolen each year across the state at a cost of nearly $4 million (annually) to farmers.

If we add the value of stud stock, loss of animal byproducts like wool or milk, and loss of future breeding potential, the annual financial impact on NSW primary producers could realistically be over $60 million. And remember, this does not consider the significant level of under-reporting crimes in rural areas.

Read more:

Crime and punishment: Rural people are more punitive than city-dwellers

These costs are also borne by farmers already facing serious challenges from droughts, flooding, bush fires, climate change and mental health issues.

Crime often cuts deeper than financial loss. In our survey, 70.3% of farmers classify crime in their local area as serious or very serious, and 64.3% are worried or very worried about crime in general.

This can have a significant impact on psychological well-being and undermine social trust. And this, in turn, can hamper the ability of communities to work together and with police to combat crime.

Rural policing in New South Wales

Farmers in our survey expressed a strong desire for the police to engage with them directly and to perform a crime prevention role. An overwhelming majority (90%) specifically supported a team of police officers trained to deal specifically with rural crime.

In 2017, a team of full-time, dedicated investigators was established in the state called the Rural Crime Prevention Team. It is comprised of detectives and intelligence analysts located strategically across the state who work solely on crimes affecting the pastoral, agricultural and aquacultural industries.

Read more:

Illegal hunters are a bigger problem on farms than animal activists – so why aren't we talking about that?

Two-thirds of farmers we surveyed said they were aware of this team. It has made significant inroads in rural areas through community engagment and high-visibility, proactive enforcement strategies.

Our survey also found that those who have had direct contact with the RCPT are more satisfied with the police, have higher levels of confidence in the police, and are more likely to report crimes. Given these results, it is important that resources continue to be allocated to increase the team’s visibility and capacity to address rural crime.

Preventing rural crime

The nature and prevalence of farm crime is heavily shaped by the location and cultural geography of rural areas.

For example, population density and physical distances between properties often means there is less risk of offenders getting caught. And the potential reward for their crimes is higher given how many valuable assets are on farms.

Police cannot simply “go it alone” in rural areas. Crime prevention is a shared responsibility for communities, with both farmers and police alike needing to adopt preventative practices.

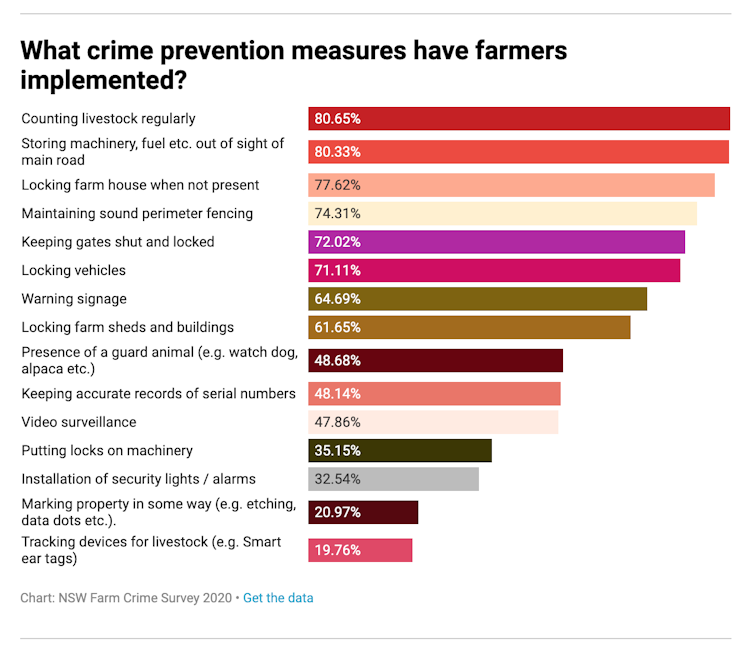

Among the farmers we surveyed, 80% felt personal responsibility to prevent farm crime, with many indicating they employ specific measures to do this.

Other reasons for non-reporting include a belief that a crime is not serious enough to report or concerns about revenge in a small community (nearly 40%).

This “dark figure of crime” — the term used to describe the number of committed crimes that are not reported or discovered — not only means the weight of the law won’t be applied to those who engage in criminality, but that policy-makers are unaware of the true extent of rural offending rates and patterns.

The effects of farm crime

Farm crime is costly. Let’s consider stock theft. NSW police figures indicate that between 2015 and 2020, an average of 1,800 cattle and 16,700 sheep were stolen each year across the state at a cost of nearly $4 million (annually) to farmers.

If we add the value of stud stock, loss of animal byproducts like wool or milk, and loss of future breeding potential, the annual financial impact on NSW primary producers could realistically be over $60 million. And remember, this does not consider the significant level of under-reporting crimes in rural areas.

Read more:

Crime and punishment: Rural people are more punitive than city-dwellers

These costs are also borne by farmers already facing serious challenges from droughts, flooding, bush fires, climate change and mental health issues.

Crime often cuts deeper than financial loss. In our survey, 70.3% of farmers classify crime in their local area as serious or very serious, and 64.3% are worried or very worried about crime in general.

This can have a significant impact on psychological well-being and undermine social trust. And this, in turn, can hamper the ability of communities to work together and with police to combat crime.

Rural policing in New South Wales

Farmers in our survey expressed a strong desire for the police to engage with them directly and to perform a crime prevention role. An overwhelming majority (90%) specifically supported a team of police officers trained to deal specifically with rural crime.

In 2017, a team of full-time, dedicated investigators was established in the state called the Rural Crime Prevention Team. It is comprised of detectives and intelligence analysts located strategically across the state who work solely on crimes affecting the pastoral, agricultural and aquacultural industries.

Read more:

Illegal hunters are a bigger problem on farms than animal activists – so why aren't we talking about that?

Two-thirds of farmers we surveyed said they were aware of this team. It has made significant inroads in rural areas through community engagment and high-visibility, proactive enforcement strategies.

Our survey also found that those who have had direct contact with the RCPT are more satisfied with the police, have higher levels of confidence in the police, and are more likely to report crimes. Given these results, it is important that resources continue to be allocated to increase the team’s visibility and capacity to address rural crime.

Preventing rural crime

The nature and prevalence of farm crime is heavily shaped by the location and cultural geography of rural areas.

For example, population density and physical distances between properties often means there is less risk of offenders getting caught. And the potential reward for their crimes is higher given how many valuable assets are on farms.

Police cannot simply “go it alone” in rural areas. Crime prevention is a shared responsibility for communities, with both farmers and police alike needing to adopt preventative practices.

Among the farmers we surveyed, 80% felt personal responsibility to prevent farm crime, with many indicating they employ specific measures to do this.

Yet, farmers also pointed out the challenges to adopting more crime-prevention measures, including the financial cost, difficulty of implementation and a lack of knowledge around what works. These challenges often discourage them.

There is still much work to be done. In our survey, 41.8% of farmers were unaware they could report a crime to Crime Stoppers, while 45% did not know they could report to the Police Assistance Line.

This is why community-based crime prevention initiatives, such as the newly launched campaign in NSW, “Draw the line on regional crime”, are so important.

The launch and success of the RCPT is a strong start, as are collaborative community engagement campaigns with Crime Stoppers. If we can continue to increase farmers’ knowledge of rural crime prevention tactics like these, this can not only reduce concerns about crime, but also boost farmers’ engagement with police, their reporting of crimes and their own crime prevention efforts.

Read more:

Australia's farmers want more climate action – and they’re starting in their own (huge) backyards

Yet, farmers also pointed out the challenges to adopting more crime-prevention measures, including the financial cost, difficulty of implementation and a lack of knowledge around what works. These challenges often discourage them.

There is still much work to be done. In our survey, 41.8% of farmers were unaware they could report a crime to Crime Stoppers, while 45% did not know they could report to the Police Assistance Line.

This is why community-based crime prevention initiatives, such as the newly launched campaign in NSW, “Draw the line on regional crime”, are so important.

The launch and success of the RCPT is a strong start, as are collaborative community engagement campaigns with Crime Stoppers. If we can continue to increase farmers’ knowledge of rural crime prevention tactics like these, this can not only reduce concerns about crime, but also boost farmers’ engagement with police, their reporting of crimes and their own crime prevention efforts.

Read more:

Australia's farmers want more climate action – and they’re starting in their own (huge) backyards

Authors: Kyle J.D. Mulrooney, Senior Lecturer in Criminology, Co-director of the Centre for Rural Criminology, University of New England