More than a decade after the Black Saturday fires, it's time we got serious about long-term disaster recovery planning

- Written by Lisa Gibbs, Academic, Population Health, The University of Melbourne

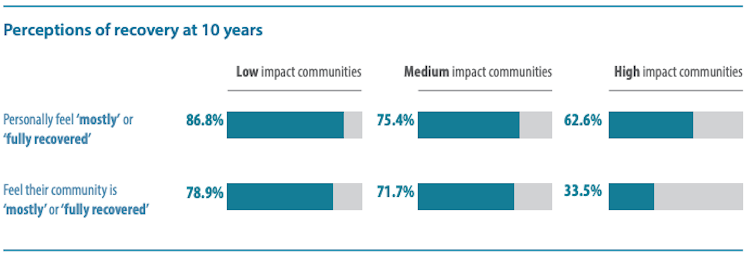

Ten years on from the 2009 Victorian Black Saturday fires, in which 173 people died, 3,500 buildings were destroyed and entire townships were wiped out, about two thirds of people from highly impacted communities reported they felt “mostly” or “fully recovered”.

Their perceptions of community recovery were much lower, however, with only about a third of people in the worst-affected areas feeling their community was “mostly” or “fully recovered”.

These are among the key findings of the Beyond the Bushfires report released today, a major investigation of the long-term impacts of one of the worst natural disasters in Australian living memory.

Beyond the Bushfires report., Author provided

As the climate warms and disasters are predicted to become more frequent and intense, the report recommends governments invest in preparing long-term frameworks for recovery from major disasters and find innovative ways to boost community resilience before, during and after the moment of crisis.

Failing to address these longer term impacts risks entrenching disadvantage, because disaster-hit communities — many of which were struggling even before the fires — can struggle for years after the flames are out.

Investing in disaster resilience now, and normalising the idea that recovery is a long-term project, can help put communities in a better position to withstand disasters when they inevitably strike.

A long tail

Our report draws on data from more than 1,000 participants who told us of their experiences through community meetings, repeated surveys (three, five and 10 years after the fires) and in-depth interviews (three to five years after the fires).

We also spent a lot of time in the first five years visiting communities, being part of community meetings and speaking with contacts built up over many years.

The main finding to emerge is that these events have a long tail. There’s no quick clean-up to get things back to normal. Mental health impacts can linger for many years. People are generally extraordinarily resilient and we need to applaud that, but the disruption to lives continues well after the initial crisis clears.

We found:

a slump in life satisfaction from three to five years after the bushfires, which improved again at ten years after the bushfires

ten years after the fires, 22% of people were reporting symptoms consistent with a diagnosable mental health disorder, including post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and psychological distress — more than twice the levels in low-impacted communities

around 10% of people in high-impacted communities reported anger problems five years after the fires. This was three times higher than in low and moderately impacted communities and more common among women, younger people and the unemployed

in the first three to four years following the bushfires, reports of violence experienced by women were seven times higher in high bushfire-affected areas when compared with low bushfire-affected regions. For women, experiences of violence were also linked with income loss and poorer mental health

a sense of community cohesion was lower in high-impact communities ten years after the bushfires

loss of income, property loss and relationship breakdown increased the risk of mental health impacts

most people who rebuilt felt the timing of their rebuild was about right.

Beyond the Bushfires report., Author provided

As the climate warms and disasters are predicted to become more frequent and intense, the report recommends governments invest in preparing long-term frameworks for recovery from major disasters and find innovative ways to boost community resilience before, during and after the moment of crisis.

Failing to address these longer term impacts risks entrenching disadvantage, because disaster-hit communities — many of which were struggling even before the fires — can struggle for years after the flames are out.

Investing in disaster resilience now, and normalising the idea that recovery is a long-term project, can help put communities in a better position to withstand disasters when they inevitably strike.

A long tail

Our report draws on data from more than 1,000 participants who told us of their experiences through community meetings, repeated surveys (three, five and 10 years after the fires) and in-depth interviews (three to five years after the fires).

We also spent a lot of time in the first five years visiting communities, being part of community meetings and speaking with contacts built up over many years.

The main finding to emerge is that these events have a long tail. There’s no quick clean-up to get things back to normal. Mental health impacts can linger for many years. People are generally extraordinarily resilient and we need to applaud that, but the disruption to lives continues well after the initial crisis clears.

We found:

a slump in life satisfaction from three to five years after the bushfires, which improved again at ten years after the bushfires

ten years after the fires, 22% of people were reporting symptoms consistent with a diagnosable mental health disorder, including post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and psychological distress — more than twice the levels in low-impacted communities

around 10% of people in high-impacted communities reported anger problems five years after the fires. This was three times higher than in low and moderately impacted communities and more common among women, younger people and the unemployed

in the first three to four years following the bushfires, reports of violence experienced by women were seven times higher in high bushfire-affected areas when compared with low bushfire-affected regions. For women, experiences of violence were also linked with income loss and poorer mental health

a sense of community cohesion was lower in high-impact communities ten years after the bushfires

loss of income, property loss and relationship breakdown increased the risk of mental health impacts

most people who rebuilt felt the timing of their rebuild was about right.

Beyond the Bushfires report., Author provided

We often see a huge outpouring of public compassion and support in the aftermath of a major disaster. But our report recommends governments and service providers ensure support (and funding) is spread over years rather than rushed out.

Among our key recommendations is that governments establish a staged five-year framework for recovery from major disasters. This would account for extended mental health impacts and support short- and long-term recovery, resilience and community connectedness.

Financial advice, help with navigating building regulations, relationship counselling and job retraining are all needed over the years following a disaster. A variety of mental health supports are also needed.

Beyond the Bushfires report., Author provided

We often see a huge outpouring of public compassion and support in the aftermath of a major disaster. But our report recommends governments and service providers ensure support (and funding) is spread over years rather than rushed out.

Among our key recommendations is that governments establish a staged five-year framework for recovery from major disasters. This would account for extended mental health impacts and support short- and long-term recovery, resilience and community connectedness.

Financial advice, help with navigating building regulations, relationship counselling and job retraining are all needed over the years following a disaster. A variety of mental health supports are also needed.

Most people who rebuilt felt the timing of their rebuild was about right, we found.

Shutterstock

Change is needed not just at the government level, but society-wide. The public needs to recognise recovery is a long-term project. There is often public pressure for agencies and governments to act quickly, which risks funds being only spent on immediate needs. There’s then precious little left for later staged interventions.

But some needs may not be initially apparent. We must allow people to recover at their own pace, in their own way and have long-term support in place to do that.

Building community can build disaster resilience

The role of social networks and community groups is incredibly important. We found people who belonged to a local community group tended to have better outcomes in the three to five years post bushfires than those who did not. These benefits seemed to extend across the wider community in areas where many people belong to local community groups.

Support for community groups means building and providing access to spaces where people can meet and socialise, supporting access to relevant equipment and materials, giving training opportunities and providing funding.

Spaces that allow people to gather and connect are crucial. But there should be more than one meeting space to allow for differences in communities.

School-based bushfire education and recovery support programs are also needed. This would teach children and teenagers how to live in bushfire-risk environments and involve them in local bushfire preparedness and recovery initiatives.

If this article has raised issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone

you know, call Lifeline on 13 11 14. This story is part of a series The Conversation is running on the nexus between disaster, disadvantage and resilience. You can read the rest of the stories here.

Most people who rebuilt felt the timing of their rebuild was about right, we found.

Shutterstock

Change is needed not just at the government level, but society-wide. The public needs to recognise recovery is a long-term project. There is often public pressure for agencies and governments to act quickly, which risks funds being only spent on immediate needs. There’s then precious little left for later staged interventions.

But some needs may not be initially apparent. We must allow people to recover at their own pace, in their own way and have long-term support in place to do that.

Building community can build disaster resilience

The role of social networks and community groups is incredibly important. We found people who belonged to a local community group tended to have better outcomes in the three to five years post bushfires than those who did not. These benefits seemed to extend across the wider community in areas where many people belong to local community groups.

Support for community groups means building and providing access to spaces where people can meet and socialise, supporting access to relevant equipment and materials, giving training opportunities and providing funding.

Spaces that allow people to gather and connect are crucial. But there should be more than one meeting space to allow for differences in communities.

School-based bushfire education and recovery support programs are also needed. This would teach children and teenagers how to live in bushfire-risk environments and involve them in local bushfire preparedness and recovery initiatives.

If this article has raised issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone

you know, call Lifeline on 13 11 14. This story is part of a series The Conversation is running on the nexus between disaster, disadvantage and resilience. You can read the rest of the stories here.

Authors: Lisa Gibbs, Academic, Population Health, The University of Melbourne