Guy Pearce shines, but The Last Vermeer paints over the remarkable true story of the world's most successful art forger

- Written by Ted Snell, Honorary Professor, Edith Cowan University

Film review: The Last Vermeer, directed by Dan Friedkin.

Among the thousands of plundered treasures discovered in May 1945 by the Allies was an undocumented picture supposedly by Johannes Vermeer, a masterpiece titled Christ and the Adulteress.

Held in the personal collection of Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, no one knew anything about it. Where had it come from? How did Göring get his hands on it?

The Last Vermeer — the first directorial outing for billionaire Dan Friedkin — recounts the fascinating story of the painting’s discovery, and exposure as a fake.

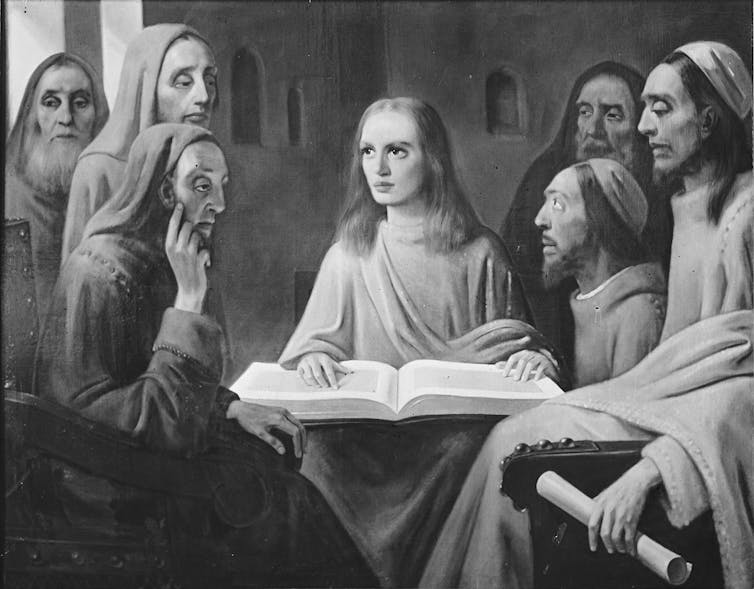

Han van Meegeren, Christ and the Adulteress, 1942.

Fundatie Museum

Han van Meegeren, Christ and the Adulteress, 1942.

Fundatie Museum

In the process, Friedkin turns a spotlight onto the art market, questioning why some artworks are worth millions and others only a few hundred dollars, and querying who makes these decisions.

Early in the film, our hero, the infamous Dutch art forger Han van Meegeren (played with flair by Guy Pearce), suggests the problem facing the film’s protagonist Captain Joseph Piller (played woodenly by Claes Bang) is not one of art. Instead, Piller should be “investigating money and power”.

From the rollicking beginning, it seems Friedkin intends to investigate just that, but after about 15 minutes, the wheels fall off. For the next hour, we lose track of the central narrative until suddenly (and unconvincingly) we arrive at the 1945 trial in which van Meegeren is accused of treason for selling national treasures to the Nazis.

Forgery as revenge

Born in 1889, the unsuccessful artist-turned-art-dealer van Meegeren was a charlatan, talented painter, bon vivant, opportunist, satirist, critic and — eventually — national hero.

Sadly, The Last Vermeer does not explore the complete and detailed narrative of this forger, the Nazi, and the art market. Instead, the film introduces a cohort of characters that confuse rather than clarify, changing and ignoring critical details of the story.

As we discover in the film, van Meegeren’s early career was impacted by negative reviews from his first solo exhibition in 1917.

To win back his self-esteem (and make himself absurdly wealthy) he began forging artworks.

Han van Meegeren painting in 1945.

Wikimedia Commons

Han van Meegeren painting in 1945.

Wikimedia Commons

One expert, art historian and curator Dr Abraham Bredius found fault with an early attempt and pronounced it a fake, instantly becoming the target for van Meergeren’s revenge.

To convince the world of his true genius, van Meegeren painted forgeries to fulfil Bredius’ theory that the Dutch master Johannes Vermeer had been influenced by Italian painting. Van Meegeren painted the quintessential “missing link” to try to prove this Italian connection.

By 1936, he had perfected his technique, painting Christ and the Disciples at Emmaus. Bredius was delighted, and arranged for the Museum Boijmans in Rotterdam to buy the painting, which he believed to be a Vermeer, for a huge sum.

In 1942, van Meegeren sold another painting, Christ and the Adulteress, as a true Vermeer to Göring.

Read more: The secret to all great art forgeries

In the film, once the plot is set up with the discovery of the treasures, the story meanders around the central characters and a lengthy exposition of antipathy between the Dutch and their liberators, before Friedkin finally returns to the core of the story.

However, here he presents a revamped version.

The film suggests van Meegeren, on trial for treason for selling Vermeers to the Nazis, convinced his jailers to allow him to paint and drink whiskey while in confinement.

The real story was much more dramatic.

Even though he could tell the jury which paintings they would find under his “Vermeers” when x-rayed (forgeries are often painted over existing paintings from the same era), the court remained unconvinced.

To settle the case, van Meegeren was set up in a house rented by the Dutch government — under the scrutiny of six witnesses — to paint another Vermeer. To their astonishment, he completed Jesus among the Doctors in a matter of weeks.

Han van Meegeren’s Jesus among the Doctors, also called Young Christ in the Temple (1945) was painted in just six weeks.

Wikimedia Commons

Han van Meegeren’s Jesus among the Doctors, also called Young Christ in the Temple (1945) was painted in just six weeks.

Wikimedia Commons

Read more: You may spot the fake at Dulwich Picture Gallery, but forgeries are no joke

Surely this is a much better cinematic scenario than the absurdity of soldiers setting their prisoner up in a studio with all the comforts of home.

Nevertheless, the result of this extraordinary evidence was so conclusive van Meegeren was convicted of forgery — not treason — in November 1947. And as the man who had swindled Göring, he became an instant folk hero for the liberated Dutch.

Sadly, his glory was short-lived. He died of a heart attack six weeks later.

Faking the fakes

Despite the rambling first half of the film, we do finally get most of the details of this extraordinary story of power, the art market, the role of critics, and how the latter two can destroy careers.

But I do feel sorry for van Meegeren, the most successful forger in history. The master forger would be rightly horrified that instead of using his own forgeries of Vermeer, Friedkin hired a scene painter named James Gemmill to create rather ham-fisted versions for his film.

Van Meegeren’s The Supper at Emmaus (1937): his forgeries are much better than the versions in the film.

Wikimedia Commons

Van Meegeren’s The Supper at Emmaus (1937): his forgeries are much better than the versions in the film.

Wikimedia Commons

Although not Vermeers, they were van Meegerens — and worthy of our admiration.

Like Göring, who according to the film’s final credits, “looked as if for the first time he had discovered there was evil in the world” when told his beloved Vermeer was a forgery, van Meegeren would be justifiably horrified by this final insult.

The Last Vermeer is in Australian cinemas from March 25.

Authors: Ted Snell, Honorary Professor, Edith Cowan University