Wake up, Mr Morrison: Australia's slack climate effort leaves our children 10 times more work to do

- Written by Lesley Hughes, Professor, Department of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University

There is much at stake at the highly anticipated United Nations climate summit in Glasgow this November. There, almost 200 nations signed up to the Paris Agreement will make emissions reduction pledges as part of the international effort to avoid catastrophic climate change.

Many countries recognise the urgent task at hand. Ahead of the meeting, more than 110 governments have already pledged to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. So where is Australia in terms of global ambition?

We, some of Australia’s most senior climate change scientists and policymakers, have come together to address these and other pressing questions, informed by sound science and policy.

Our report, released today, pinpoints the emissions reduction burden Australians will bear in future decades if our Paris targets are not increased. Alarmingly, people living in the 2030s and 2040s could be forced to reduce emissions by ten times as much as people this decade, if Australia is to keep within its 2℃ “carbon budget”.

Without policy change, people living in coming decades will have to reduce emissions by far more than the current rate.

Dean Lewins/AAP

Without policy change, people living in coming decades will have to reduce emissions by far more than the current rate.

Dean Lewins/AAP

‘Manifestly inadequate’

A “carbon budget” identifies how much carbon dioxide (CO₂) the world can emit if it’s to limit global temperature rise to internationally agreed goals. Those goals include keeping warming to well below 2℃ – and preferably below 1.5℃ – this century.

National emissions reduction targets are key to staying within a carbon budget. Australia’s target, under the Paris Agreement, is a 26-28% reduction between 2005 and 2030.

In a report released in January, we showed how that target is manifestly inadequate. To remain within its 2°C carbon budget, Australia must cut emissions by 50% between 2005 and 2030, and reach net-zero emissions by 2045.

To remain inside the 1.5°C budget, we must reduce emissions by 74% between 2005 and 2030, and reach net zero emissions by 2035.

Since that report was released, the Australian government has doubled down on its 2030 target. But Prime Minister Scott Morrison appears to be inching closer to a net-zero commitment. Last month he declared his government’s goal was “to reach net-zero emissions as soon as possible, and preferably by 2050”.

Our latest report set out to determine how the burden of emissions reduction would be spread after 2030 if Australia’s 2030 target is not increased.

Read more: Scott Morrison has embraced net-zero emissions – now it's time to walk the talk

The Morrison government is sticking with its inadequate Paris pledge.

Shutterstock

The Morrison government is sticking with its inadequate Paris pledge.

Shutterstock

What we found

Our analysis used the methodology adopted by the Climate Change Authority. This statutory body was established by the Gillard Labor government in 2012, and was charged with providing independent expert policy advice.

In 2014, the authority identified the level of climate ambition required for Australia to do its fair share in the global effort. It recommended a 30% emissions reduction between 2000 and 2025, reaching 40-60% by 2030.

But the Abbott Coalition government ignored this advice. Instead, it pledged the far weaker target of 26-28% emissions reduction.

We wanted to determine what happens if Australia sticks to that inadequate target – and so delays substantive climate action until later decades.

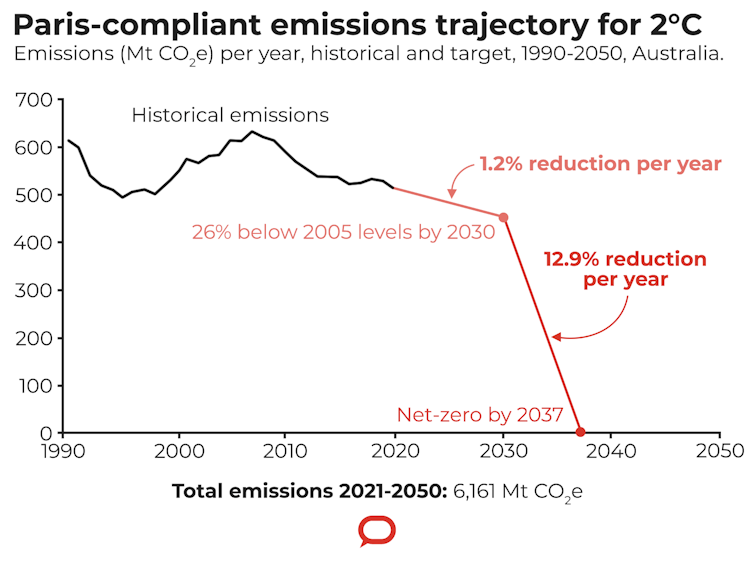

To meet the weak Paris target, Australia need only reduce emissions by 1.2% each year from 2020 to 2030. If Australia persists with this target but still decides to stay inside the 2℃ carbon budget, that leaves just 1,329 million tonnes of greenhouse gases we can emit after 2030.

Keeping to this limit would be extremely challenging. If done in a straight-line trajectory, it would mean a 12.9% cut in emissions each year from 2030, until net-zero emissions were reached in 2037.

This represents an annual challenge ten times greater than what’s needed in each year this decade to meet the current 2030 goals. It would require an annual emissions reduction of 66.8 million tonnes of greenhouse gases – more than every car and light commercial vehicle on Australia’s roads emits in a year.

Author provided/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

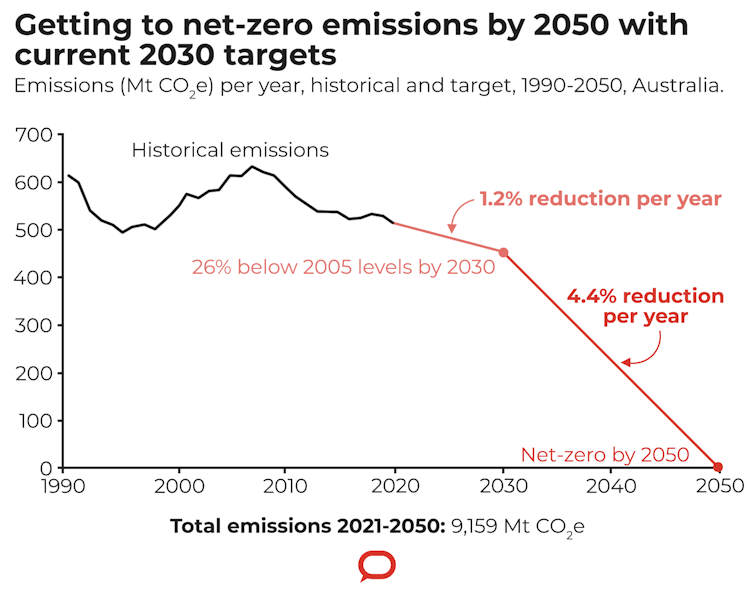

Second, we looked at the emissions trajectory if Australia was to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, while still keeping the inadequate 2030 Paris targets. We found people living in the 2030s and 2040s would have to reduce emissions by three times more than what’s required this decade.

Author provided/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Second, we looked at the emissions trajectory if Australia was to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, while still keeping the inadequate 2030 Paris targets. We found people living in the 2030s and 2040s would have to reduce emissions by three times more than what’s required this decade.

Emissions include land-use, landuse change and forestry emissions. A drop in widespread land clearing creates the impression of overall reduced emissions. But underlying fossil fuel and industrial emissions have steadily increased since the 1990s - with the exception of brief moments when Australia had an effective price on carbon.

Author provided/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Clearly, the inadequate 2030 target is the source of the problem. By requiring very little emissions reduction this decade, the Morrison government is kicking the climate can down the road for our children to pick up. It means Australia is also failing on its moral obligation to do its fair share in the global climate effort.

Australia trails the world

This sad state of affairs is not news to the rest of the world. Australia is widely viewed as an international climate laggard. In the 2020 Climate Change Performance Index, it received the lowest rating of 57 countries and the European Union. It also ranked second-worst on climate action, out of 177 countries, in the 2020 UN Sustainable Development Report.

The Glasgow climate summit, known as the 26th Conference of the Parties or COP26, seeks to hold governments to account for their climate pledges. Nations are expected to front up with ambitious short-term plans for emissions reduction.

Many nations have risen to the challenge. Countries to adopt a target of net-zero by 2050 include the United States, Japan, South Korea and the European Union. China will aim to achieve this target by 2060.

Even more importantly, some governments have ramped up their 2030 targets. For example the European Union will now reduce emissions by 55% and the United Kingdom by 68% – both on 1990 levels.

Read more:

Biden’s Senate majority doesn't just super-charge US climate action, it blazes a trail for Australia

Emissions include land-use, landuse change and forestry emissions. A drop in widespread land clearing creates the impression of overall reduced emissions. But underlying fossil fuel and industrial emissions have steadily increased since the 1990s - with the exception of brief moments when Australia had an effective price on carbon.

Author provided/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Clearly, the inadequate 2030 target is the source of the problem. By requiring very little emissions reduction this decade, the Morrison government is kicking the climate can down the road for our children to pick up. It means Australia is also failing on its moral obligation to do its fair share in the global climate effort.

Australia trails the world

This sad state of affairs is not news to the rest of the world. Australia is widely viewed as an international climate laggard. In the 2020 Climate Change Performance Index, it received the lowest rating of 57 countries and the European Union. It also ranked second-worst on climate action, out of 177 countries, in the 2020 UN Sustainable Development Report.

The Glasgow climate summit, known as the 26th Conference of the Parties or COP26, seeks to hold governments to account for their climate pledges. Nations are expected to front up with ambitious short-term plans for emissions reduction.

Many nations have risen to the challenge. Countries to adopt a target of net-zero by 2050 include the United States, Japan, South Korea and the European Union. China will aim to achieve this target by 2060.

Even more importantly, some governments have ramped up their 2030 targets. For example the European Union will now reduce emissions by 55% and the United Kingdom by 68% – both on 1990 levels.

Read more:

Biden’s Senate majority doesn't just super-charge US climate action, it blazes a trail for Australia

Under President Joe Biden, the US will work towards net-zero emissions by 2050.

Carolyn Kaster/AP/AAP

A critical decade

The importance of COP26 cannot be overstated. Under current global pledges, an average temperature rise of 3℃ or more is distinctly possible this century. This increases the risk of abrupt and irreversible changes in the Earth’s climate system - known as tipping points - bringing disastrous consequences for both human and natural systems.

The Morrison government is failing to protect Australia from this devastating future. It’s also ignoring a major economic opportunity that should - in a rational country - bring all sides of politics together.

Over the past decade, renewable energy costs have plummeted and significant advances have been made in electric vehicles and regenerative agriculture. This opens up vast new opportunities for Australia.

These days, few in the federal Coalition would deny climate science outright. But the government’s softer form of denial – failing to grasp the need for urgent action – will have the same tragic outcome.

Read more:

Against the odds, South Australia is a renewable energy powerhouse. How on Earth did they do it?

Under President Joe Biden, the US will work towards net-zero emissions by 2050.

Carolyn Kaster/AP/AAP

A critical decade

The importance of COP26 cannot be overstated. Under current global pledges, an average temperature rise of 3℃ or more is distinctly possible this century. This increases the risk of abrupt and irreversible changes in the Earth’s climate system - known as tipping points - bringing disastrous consequences for both human and natural systems.

The Morrison government is failing to protect Australia from this devastating future. It’s also ignoring a major economic opportunity that should - in a rational country - bring all sides of politics together.

Over the past decade, renewable energy costs have plummeted and significant advances have been made in electric vehicles and regenerative agriculture. This opens up vast new opportunities for Australia.

These days, few in the federal Coalition would deny climate science outright. But the government’s softer form of denial – failing to grasp the need for urgent action – will have the same tragic outcome.

Read more:

Against the odds, South Australia is a renewable energy powerhouse. How on Earth did they do it?

Authors: Lesley Hughes, Professor, Department of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University