My favourite detective: Martin Hewitt, the cheery yet gritty antidote to Sherlock Holmes

- Written by Stephen Knight, Honorary Research Professor, The University of Melbourne

In this series, writers pay tribute to fictional detectives on the page and on screen.

Arthur Morrison’s detective Martin Hewitt first appeared in The Strand magazine in March 1894. It was four months after Conan Doyle had published The Final Problem, reporting the death of Sherlock Holmes, in the magazine. Hewitt was Morrison’s replacement for, and conscious opposite to, the “great detective”. Hewitt is unassuming, practical, democratic — and admirably realistic.

Morrison, also famous for the Tales of Mean Streets (1894) and the novel A Child of the Jago (1896), wrote tough East End realism — drawing on his own place of origin. He objected to the improbabilities of Holmesian detection. Both investigators watch people in detail, but Hewitt never offers the operatic deductions and insights that made Holmes mythically famous: he simply follows up the implications of what he has carefully observed.

Read more: My favourite detective: Jules Maigret, the Paris detective with a pipe but no pretence

Looking for clues

Goodreads

Hewitt’s base is humble: his office is up a “dingy staircase” where a “dusty ground-glass upper panel” on its door simply reads “Hewitt”. He does, like Holmes, have a narrator-friend. Named Brett, he is a fairly inactive bachelor lawyer-turned-journalist and the two are simply acquaintances, not in a lord-and-master relationship like Holmes and Watson.

In personal terms Hewitt is unlike the hyper-heroic Holmes, being a “stoutish, clean-shaven man, of middle height, and of a cheerful, round countenance”, with a “cheery, chaffing good nature”.

The major difference between Hewitt and Holmes though is their method of detection: Brett notes Hewitt:

… had always as little of the aspect of the conventional detective as may be imagined. Nobody could appear more cordial or less observant in manner, although there was to be seen a certain sharpness of the eye.

Holmes has both rich historical recall and remarkable, even improbable, powers of deduction. Hewitt possesses “no system beyond a judicious use of ordinary faculties”. While Holmes shows only contempt for the police, Hewitt welcomes their cooperation. The American scholar E. F. Bleiler, editor of The Best Martin Hewitt Stories (1976), saw Morrison’s detective as “deliberately low-key”.

Hewitt’s background also bestows him with some radically non-Holmesian powers — in one story a grim crime is solved through his ability to speak the Gypsy language. Elsewhere he shows a fluent command of London criminal slang, with explanatory footnotes. But it is Hewitt’s realistic, commonsense method that is the two characters’ main separation.

In one early story a house has seen three thefts of small jewels. Access to the rooms is impossible. In each case a used match is found near the missing object’s location — yet nighttime robbery is also ruled out. Hewitt studies the matches closely, then checks everyone linked to the house. One of them, as he expected, has a parrot. The bird has been trained to fly in through slightly open windows, drop the beak-marked match (held there on command to stop it squawking), and bring a jewel to its cunning owner.

Read more:

My favourite detective: Kurt Wallander — too grumpy to like, relatable enough to get under your skin

Taking notice

Hewitt’s observation can be brisker. In another case a man is distressed by the loss of his plans for a very valuable torpedo. The detective watches as two staff search the office: suddenly a cross man appears, waving his hat and stick, demanding to see the designer. After they send him away, Hewitt settles them all down in the inner office — and produces the missing plans.

Goodreads

Hewitt’s base is humble: his office is up a “dingy staircase” where a “dusty ground-glass upper panel” on its door simply reads “Hewitt”. He does, like Holmes, have a narrator-friend. Named Brett, he is a fairly inactive bachelor lawyer-turned-journalist and the two are simply acquaintances, not in a lord-and-master relationship like Holmes and Watson.

In personal terms Hewitt is unlike the hyper-heroic Holmes, being a “stoutish, clean-shaven man, of middle height, and of a cheerful, round countenance”, with a “cheery, chaffing good nature”.

The major difference between Hewitt and Holmes though is their method of detection: Brett notes Hewitt:

… had always as little of the aspect of the conventional detective as may be imagined. Nobody could appear more cordial or less observant in manner, although there was to be seen a certain sharpness of the eye.

Holmes has both rich historical recall and remarkable, even improbable, powers of deduction. Hewitt possesses “no system beyond a judicious use of ordinary faculties”. While Holmes shows only contempt for the police, Hewitt welcomes their cooperation. The American scholar E. F. Bleiler, editor of The Best Martin Hewitt Stories (1976), saw Morrison’s detective as “deliberately low-key”.

Hewitt’s background also bestows him with some radically non-Holmesian powers — in one story a grim crime is solved through his ability to speak the Gypsy language. Elsewhere he shows a fluent command of London criminal slang, with explanatory footnotes. But it is Hewitt’s realistic, commonsense method that is the two characters’ main separation.

In one early story a house has seen three thefts of small jewels. Access to the rooms is impossible. In each case a used match is found near the missing object’s location — yet nighttime robbery is also ruled out. Hewitt studies the matches closely, then checks everyone linked to the house. One of them, as he expected, has a parrot. The bird has been trained to fly in through slightly open windows, drop the beak-marked match (held there on command to stop it squawking), and bring a jewel to its cunning owner.

Read more:

My favourite detective: Kurt Wallander — too grumpy to like, relatable enough to get under your skin

Taking notice

Hewitt’s observation can be brisker. In another case a man is distressed by the loss of his plans for a very valuable torpedo. The detective watches as two staff search the office: suddenly a cross man appears, waving his hat and stick, demanding to see the designer. After they send him away, Hewitt settles them all down in the inner office — and produces the missing plans.

Storytel

He explains he noticed that on arrival the hyperactive man had carefully placed a walking-stick in the umbrella-stand — and taken one away as he hurried off. The remaining stick, Hewitt found, was a metal tube with a wooden cover, and a screw-cap: the plans were rolled up inside. The man had copied and returned them, helped by a young assistant who confesses to the theft.

Hewitt continued his calm observation and meticulous detection for ten years and 24 stories. In later tales he travels more and, like Holmes, becomes involved in espionage matters, but also in interesting crimes based on anarchism, and even hypnotism.

After The Red Triangle (1903) there were no more Hewitt-focused narratives.

Read more:

My favourite detective: why Vera is so much more than a hat, mac and attitude

Less hero, more detection

Morrison was a restless and inventive spirit, as well as a realist who could turn his writing skills to varied genres and subjects. Before his Hewitt stories he had published a set of ghost stories (1891), then an illustrated series about animals called Zig-Zags at the Zoo (1892).

Storytel

He explains he noticed that on arrival the hyperactive man had carefully placed a walking-stick in the umbrella-stand — and taken one away as he hurried off. The remaining stick, Hewitt found, was a metal tube with a wooden cover, and a screw-cap: the plans were rolled up inside. The man had copied and returned them, helped by a young assistant who confesses to the theft.

Hewitt continued his calm observation and meticulous detection for ten years and 24 stories. In later tales he travels more and, like Holmes, becomes involved in espionage matters, but also in interesting crimes based on anarchism, and even hypnotism.

After The Red Triangle (1903) there were no more Hewitt-focused narratives.

Read more:

My favourite detective: why Vera is so much more than a hat, mac and attitude

Less hero, more detection

Morrison was a restless and inventive spirit, as well as a realist who could turn his writing skills to varied genres and subjects. Before his Hewitt stories he had published a set of ghost stories (1891), then an illustrated series about animals called Zig-Zags at the Zoo (1892).

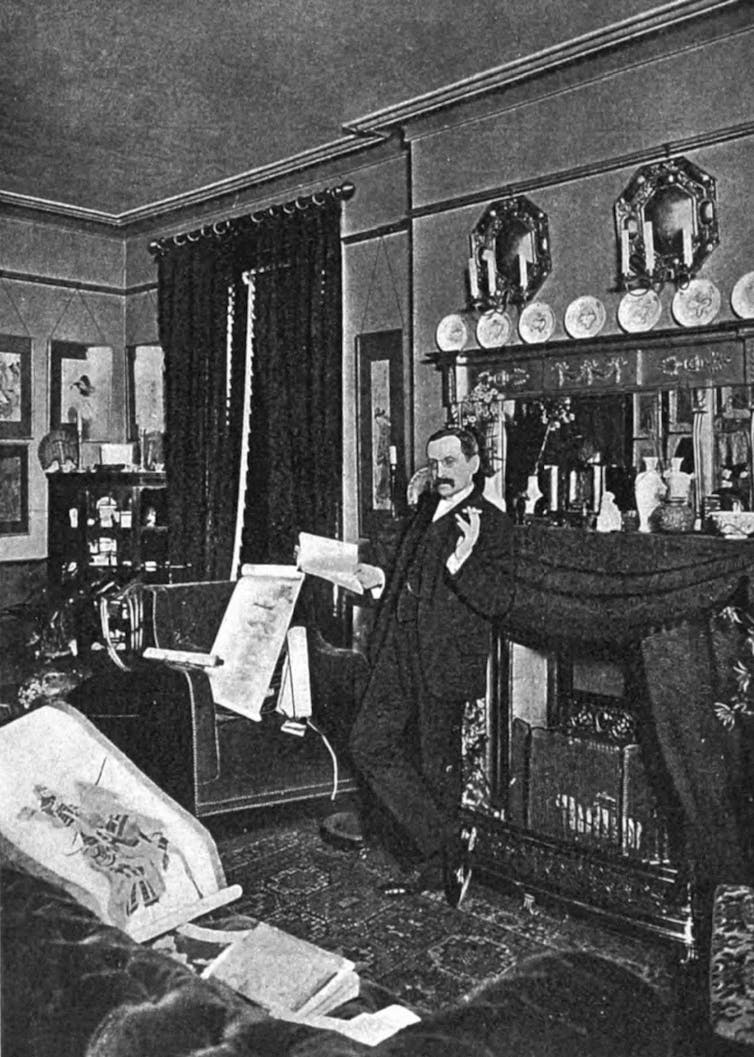

Author Arthur Morrison at home.

Wikimedia Commons/The Bookman

Alongside Hewitt, he published The Dorrington Deed-Box (1897), six stories about a “respected but deeply corrupt private detective”. Dorrington’s activities are “of a more than questionable sort”, including getting tangled up in murder. In a final development Morrison, who lived till 1945, became an expert on Japanese art.

Hewitt was the first and sharpest of the many Holmes variations and responses in busy 1890s London, as detective stories really took off. Another notable creation was Loveday Brooke, the lively female detective produced by Catherine Pirkis in 1894.

Hewitt is a memorable, admirable critique of the pomposity of Sherlock Holmes. The latter’s romantic heroism remains less credible than the observant achievements of Martin Hewitt, Arthur Morrison’s plain-man detective.

Author Arthur Morrison at home.

Wikimedia Commons/The Bookman

Alongside Hewitt, he published The Dorrington Deed-Box (1897), six stories about a “respected but deeply corrupt private detective”. Dorrington’s activities are “of a more than questionable sort”, including getting tangled up in murder. In a final development Morrison, who lived till 1945, became an expert on Japanese art.

Hewitt was the first and sharpest of the many Holmes variations and responses in busy 1890s London, as detective stories really took off. Another notable creation was Loveday Brooke, the lively female detective produced by Catherine Pirkis in 1894.

Hewitt is a memorable, admirable critique of the pomposity of Sherlock Holmes. The latter’s romantic heroism remains less credible than the observant achievements of Martin Hewitt, Arthur Morrison’s plain-man detective.

Authors: Stephen Knight, Honorary Research Professor, The University of Melbourne