The Moon plays an important role in Indigenous culture and helped win a battle over sea rights

- Written by Duane W. Hamacher, Associate Professor, University of Melbourne

The New Moon this month marks the start of the Lunar New Year and reminds us of how important our orbiting neighbour is to us.

It’s a relationship long described by many cultures across the globe, particularly with its links to tides and weather.

In the Torres Strait it was a crucially important element in helping the islanders win a legal battle for sea rights.

Under a Meriam Moon

In the Torres Strait, the Moon plays an important role in culture, identity and daily life. Every aspect of our natural satellite - from its phase, position, appearance and brightness - has special significance and meaning.

A traditional story of the Meriam people from Mer (Murray Island), in the eastern Torres Strait, explains how you can see a lady in the Full Moon weaving mats.

Read more: Why do different cultures see such similar meanings in the constellations?

She was brought there by the Moon Man, which describes the formation of the maria (dark patches) on its surface that form the silhouette of the woman.

Meriam elder Uncle Alo Tapim telling the story about the lady in the Moon.Tides of change

Lunar phases link to the changing tides, a relationship that is well established in Islander knowledge systems.

One practical application links to fishing. Elders teach that the best time to fish is during a neap (low) tide during the First or Last Quarter Moon, rather than a spring (high) tide during the New or Full Moon phase.

The spring tides are much bigger, meaning the tidal waters rush in and out more significantly, stirring up silt and sediment on the sea floor. This clouds the water, making it harder for fish to see the bait and fishers to see the fish.

The waters of spring tides also pull fish out to sea. During the smaller neap tides, the water is clearer and fish don’t move as far, making them easier to see and catch.

Gardeners such as Meriam elder Uncle Alo Tapim (below) plant their gardens by the phases of the Moon. The cusps (tips) of the crescent Moon (kerkar meb) point in different directions throughout the year, as we move from summer solstice to winter solstice and back again.

Meriam elders Alo Tapim (left) and Segar Passi (right).

Author provided

Meriam elders Alo Tapim (left) and Segar Passi (right).

Author provided

Uncle Segar Passi (above), a senior Meriam elder, teaches that when the Moon cusps point upwards (Meb metalug em), the Moon looks like a bowl collecting water. The water is choppy and you will see cumulus clouds in the sky. This occurs during the Sager (dry season), a period of fine weather.

When the Moon tilts on its side (Meb uag em), thin cirrus clouds are visible and a fuzzy ring may form around the Moon. The seas look calm and mirror-flat and you will see thin cirrus clouds, but this is when the water pours out of the bowl, falling as the rains of the Kuki (wet season).

A crescent Moon.

Pixabay

A crescent Moon.

Pixabay

Moon halos are used to forecast weather. In the Torres Strait, the ring around the Moon (susri) is seen to be a hut built by the Moon Man to shield himself from coming rain.

Halos form around the Moon when moonlight passes through ice crystals high in the atmosphere. These form in low fronts, which often bring rain.

An eclipse of the Moon

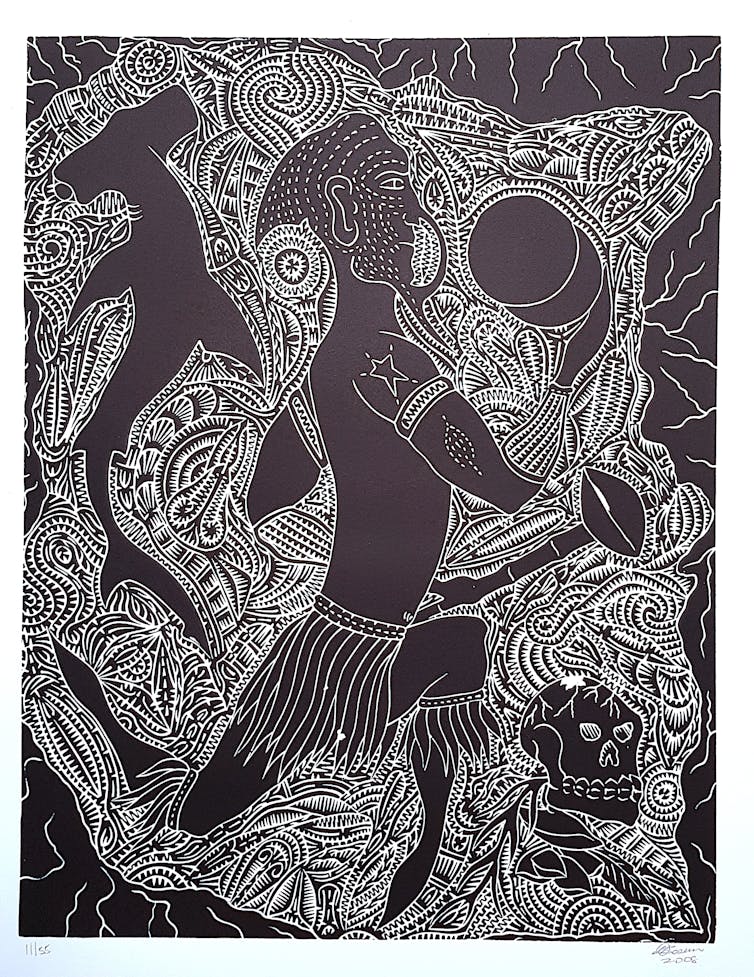

On Badu, in the Torres Strait, an eclipse of the Moon is called Merlpal Maru Pathanu, meaning “the ghost has taken the spirit of the Moon”.

It was an omen of war. On Boigu, the northern-most island, men would don a special headdress and perform a ceremony to figure out the direction of the incoming attack.

The same name is used for a solar eclipse, which is seen as the superposition of the two celestial bodies.

Merlpal Maru Pathanu … ‘the ghost has taken the spirit of the Moon’.

David Bosun (Senior artist at Moa Arts). Author provided from private collection, reproduced with permission of the artist.

Merlpal Maru Pathanu … ‘the ghost has taken the spirit of the Moon’.

David Bosun (Senior artist at Moa Arts). Author provided from private collection, reproduced with permission of the artist.

A battle for sea rights

Every June 3, Australia celebrates Mabo Day, marking the decision by the High Court of Australia to overturn the legal fiction of terra nullius (“a land belonging to no one”) in a landmark court case.

This was driven by Meriam man Edward Koike Mabo, paving the way for Native Title. But this ruling did not necessarily extend to sea rights.

In the early 2000s, the people of Mer launched a legal battle for sea rights. Government lawyers argued against the declaration by claiming each island was a separate enclave with no connection to one another.

But Torres Strait Islanders have a long history of cultural, linguistic and family connections across the Strait and with Papua New Guinea and mainland Australia.

During the proceedings, Meriam people were required to prove their longstanding connections in court. One crucial piece of evidence was a traditional Moon Dance.

Gedge Togia

Gedge Togia is a sacred spiritual dance (kab kar) of the Meriam people, linking the islands of Mabuyag (also known as Mabuiag) and Mer.

Map of the Torres Strait with the islands of Mabuiag (Mabuyag) and Mer (circled red).

Wikimedia/Kwamikagami, CC BY-SA

Map of the Torres Strait with the islands of Mabuiag (Mabuyag) and Mer (circled red).

Wikimedia/Kwamikagami, CC BY-SA

The lyrics are “Gedge Togia, Milpanuka”, which means “Moon rising over home” in two languages: Gedge Togia is the Meriam Mir language phrase meaning “to rise over home”, and Milpanuka is the Mabuyag dialect term for the Moon, which is derived from Milpal, a Kala Lagau Ya word for the Full Moon. For comparison, the Meriam Mir name of the Moon is Meb.

Read more: Kindred skies: ancient Greeks and Aboriginal Australians saw constellations in common

During legal proceedings in the mid-2000s, a judge travelled to Mer and observed testimony presented by elders. Alo Tapim sang the song and explained the dance, the traditional dress and its importance and relevance to Meriam and Mabuyag connections.

A performance of Gedge Togia, explaned by Alo Tapim.Mabuyag and Mer are 200km apart, lying almost due east and west of one another. As Meriam people sail home from Mabuyag they will see the Full Moon rising over Mer at dusk or the crescent Moon rising at dawn.

Gedge Togia and the Moon demonstrates the longstanding connections between Mer and Mabuyag, and helped Islanders win their battle for sea rights.

Authors: Duane W. Hamacher, Associate Professor, University of Melbourne