Australia must control its killer cat problem. A major new report explains how, but doesn't go far enough

- Written by Sarah Legge, Professor, Australian National University

Australia is teeming with cats. While cats make great pets, and can bring owners emotional, psychological and health benefits, the animals are a scourge on native wildlife.

Cats kill a staggering 1.7 billion native animals each year, and have played a major role in most of Australia’s 34 mammal extinctions. They continue to pose an extinction threat to at least another 120 species.

The long-nosed potoroo is extremely vulnerable to cats.

Shutterstock

The long-nosed potoroo is extremely vulnerable to cats.

Shutterstock

A recent parliamentary inquiry into the problem of feral and pet cats in Australia has affirmed the issue is indeed of national significance. The final report, released last week, calls for a heightened, more effective, multi-pronged and coordinated policy, management and research response.

As ecologists, we’ve collectively spent more than 50 years researching Australia’s cat dilemma. We welcome most of the report’s recommendations, but in some areas it doesn’t go far enough, missing major opportunities to make a difference.

Night curfews aren’t good enough

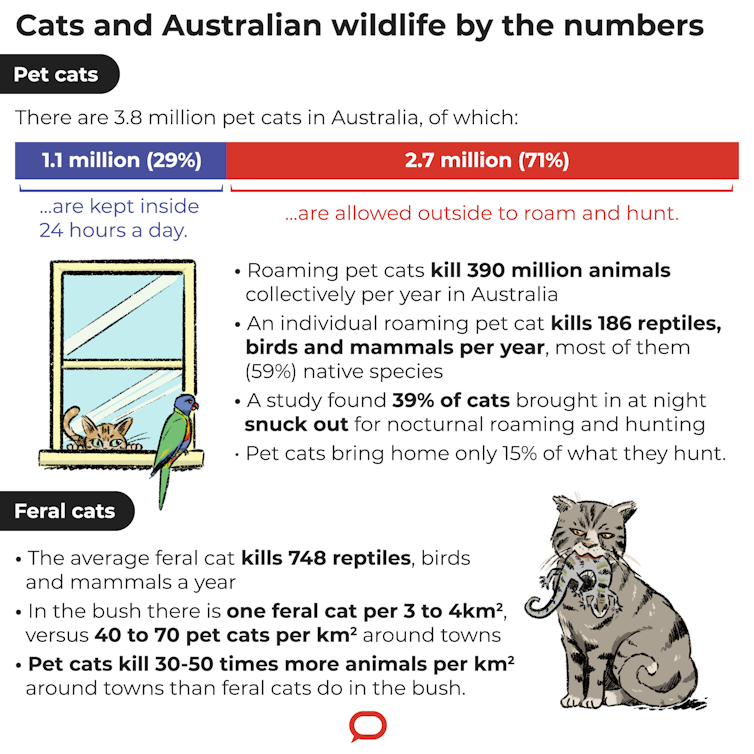

The report recommends Australia’s 3.8 million pet cats be subject to night-time curfews. This measure would benefit native nocturnal mammals, but won’t save birds and reptiles, which are primarily active during the day.

Wes Mountain/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Pet cats kill 83 million native reptiles and 80 million native birds in Australia each year. From a wildlife perspective, keeping pet cats contained 24/7 is the only responsible option.

It’s clearly possible: one third of Australian pet cat owners already keep their pets contained all the time.

Stopping pet cats from roaming is also good for the cats, which live longer, safer lives when kept exclusively indoors. It would also substantially reduce the number of people falling ill from cat-dependent diseases each year.

Read more:

Cats carry diseases that can be deadly to humans, and it's costing Australia $6 billion every year

Other strategies for improving pet cat management proposed in the report include pet cat registration, subsidised programs for early age desexing, public education campaigns to promote responsible pet cat ownership, and improving the consistency of rules and legislation nationally.

Wes Mountain/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Pet cats kill 83 million native reptiles and 80 million native birds in Australia each year. From a wildlife perspective, keeping pet cats contained 24/7 is the only responsible option.

It’s clearly possible: one third of Australian pet cat owners already keep their pets contained all the time.

Stopping pet cats from roaming is also good for the cats, which live longer, safer lives when kept exclusively indoors. It would also substantially reduce the number of people falling ill from cat-dependent diseases each year.

Read more:

Cats carry diseases that can be deadly to humans, and it's costing Australia $6 billion every year

Other strategies for improving pet cat management proposed in the report include pet cat registration, subsidised programs for early age desexing, public education campaigns to promote responsible pet cat ownership, and improving the consistency of rules and legislation nationally.

Indoor cats live longer than cats allowed to roam.

Jaana Dielenberg

The report is also unambiguously opposed to “trap-neuter-release” programs, in which un-owned cats in urban areas are desexed and then released. We agree with this finding, as these programs aren’t effective at reducing the population of stray cats, nor preventing those cats from killing wildlife and spreading disease.

We need more wildlife havens

One of the inquiry’s flagship recommendations is a national conservation project dubbed “Project Noah”. This would involve an ambitious expansion of Australia’s existing network of reserves free from introduced predators, both on islands and in mainland fenced areas. The reserves provide havens — or a fleet of “arks” — for vulnerable native wildlife.

This measure is vital. 2019 research found Australia has more than 65 native mammal species and subspecies that can’t persist, or struggle to persist, in places with even very low numbers of cats or foxes. This includes the bilby, numbat, quokka, dibbler and black-footed rock wallaby.

Indoor cats live longer than cats allowed to roam.

Jaana Dielenberg

The report is also unambiguously opposed to “trap-neuter-release” programs, in which un-owned cats in urban areas are desexed and then released. We agree with this finding, as these programs aren’t effective at reducing the population of stray cats, nor preventing those cats from killing wildlife and spreading disease.

We need more wildlife havens

One of the inquiry’s flagship recommendations is a national conservation project dubbed “Project Noah”. This would involve an ambitious expansion of Australia’s existing network of reserves free from introduced predators, both on islands and in mainland fenced areas. The reserves provide havens — or a fleet of “arks” — for vulnerable native wildlife.

This measure is vital. 2019 research found Australia has more than 65 native mammal species and subspecies that can’t persist, or struggle to persist, in places with even very low numbers of cats or foxes. This includes the bilby, numbat, quokka, dibbler and black-footed rock wallaby.

Boodies used to occur across two-thirds of Australia, but now only exist within havens.

McGregor/Arid Recovery

Australia already has more than 125 havens, 100 of which are islands. These have prevented 13 mammal species from going extinct, such as boodies and greater stick-nest rats. In total, these havens have protected populations of 40 mammal species susceptible to cats and foxes.

This is a good start, but we need more investment in havens to prevent extinctions. More than 25 species are highly sensitive to cat and fox predation, but aren’t yet protected in the haven network. This includes the central rock-rat, which is more likely than not to become extinct within 20 years without new action.

What’s more, some species, such as the long-nosed potoroo, exist in just one haven. To avoid issues such as inbreeding and to ensure disasters like a fire at any single haven don’t take out an entire species, each species should be represented across several havens, in reasonable population sizes.

The report didn’t specify how the havens network should be expanded. But 2019 research found to get each species needing protection into at least three havens, Australia requires at least 35 new, strategically located islands or mainland fenced areas.

Boodies used to occur across two-thirds of Australia, but now only exist within havens.

McGregor/Arid Recovery

Australia already has more than 125 havens, 100 of which are islands. These have prevented 13 mammal species from going extinct, such as boodies and greater stick-nest rats. In total, these havens have protected populations of 40 mammal species susceptible to cats and foxes.

This is a good start, but we need more investment in havens to prevent extinctions. More than 25 species are highly sensitive to cat and fox predation, but aren’t yet protected in the haven network. This includes the central rock-rat, which is more likely than not to become extinct within 20 years without new action.

What’s more, some species, such as the long-nosed potoroo, exist in just one haven. To avoid issues such as inbreeding and to ensure disasters like a fire at any single haven don’t take out an entire species, each species should be represented across several havens, in reasonable population sizes.

The report didn’t specify how the havens network should be expanded. But 2019 research found to get each species needing protection into at least three havens, Australia requires at least 35 new, strategically located islands or mainland fenced areas.

The predator proof fence at the Australian Wildlife Conservancy’s Newhaven Sanctuary, one of the largest cat- and fox-free havens on mainland Australia.

Australian Wildlife Conservancy

What about the rest of the country?

Havens cover less than 1% of Australia. So what we do in the other 99% of the landscape — including across conservation reserves like national parks — is vital.

Yet the parliamentary inquiry report lacks clear recommendations to expand cat control more broadly, including at important conservation sites such as in Kakadu National Park.

The impact of roaming pet cats on Australian wildlife.The report reaffirms the need to cull feral cats, and to set new targets for culling, without specifying what those targets are. We agree some culling is important, especially at sites with very vulnerable threatened wildlife.

But in many parts of Australia, broad-scale habitat management is a more cost-effective way to reduce cat harm. This involves making habitat less suitable for cats and more suitable for native wildlife, for example, by reducing rabbit numbers, fire frequency and grazing by feral herbivores such as cattle and horses.

Research has shown fewer rabbits leads to fewer cats. Rabbits are a favoured prey of many cats, so they boost feral cat numbers, which then also hunt native wildlife.

Read more:

One cat, one year, 110 native animals: lock up your pet, it's a killing machine

And cats gravitate to areas with less vegetation because it’s easier to catch prey. These areas include those with frequent fires, or where feral herbivores have reduced vegetation through grazing and trampling.

Better habitat with more vegetation gives native animals places to hide from predators, and more food and shelter. It’s a bit like giving the last little pig a house of bricks instead of trying to fist-fight the wolf.

The predator proof fence at the Australian Wildlife Conservancy’s Newhaven Sanctuary, one of the largest cat- and fox-free havens on mainland Australia.

Australian Wildlife Conservancy

What about the rest of the country?

Havens cover less than 1% of Australia. So what we do in the other 99% of the landscape — including across conservation reserves like national parks — is vital.

Yet the parliamentary inquiry report lacks clear recommendations to expand cat control more broadly, including at important conservation sites such as in Kakadu National Park.

The impact of roaming pet cats on Australian wildlife.The report reaffirms the need to cull feral cats, and to set new targets for culling, without specifying what those targets are. We agree some culling is important, especially at sites with very vulnerable threatened wildlife.

But in many parts of Australia, broad-scale habitat management is a more cost-effective way to reduce cat harm. This involves making habitat less suitable for cats and more suitable for native wildlife, for example, by reducing rabbit numbers, fire frequency and grazing by feral herbivores such as cattle and horses.

Research has shown fewer rabbits leads to fewer cats. Rabbits are a favoured prey of many cats, so they boost feral cat numbers, which then also hunt native wildlife.

Read more:

One cat, one year, 110 native animals: lock up your pet, it's a killing machine

And cats gravitate to areas with less vegetation because it’s easier to catch prey. These areas include those with frequent fires, or where feral herbivores have reduced vegetation through grazing and trampling.

Better habitat with more vegetation gives native animals places to hide from predators, and more food and shelter. It’s a bit like giving the last little pig a house of bricks instead of trying to fist-fight the wolf.

Feral horses, such as these in Kakadu National Park, eat and damage vegetation making conditions more favourable for cats to hunt.

Jaana Dielenberg

A major step forward

Over the past two decades, Australia has slowly woken up to the damage cats cause to nature. This has led to more research, management and policy to address the problem.

Some state governments, environment groups and scientists have worked hard to develop feral cat control options, and the 2015 Australian Threatened Species Strategy did much to focus national attention and resourcing to the issue.

Read more:

Don't let them out: 15 ways to keep your indoor cat happy

The parliamentary inquiry is a major step forward, and many recommendations are sound. But overall, its recommendations call for incremental improvement.

Australia’s laws clearly fail to provide a safety net for wildlife. The cat issue is part of a larger problem with how we manage habitat, biodiversity and threats to nature – and fixing that requires wholesale change.

Feral horses, such as these in Kakadu National Park, eat and damage vegetation making conditions more favourable for cats to hunt.

Jaana Dielenberg

A major step forward

Over the past two decades, Australia has slowly woken up to the damage cats cause to nature. This has led to more research, management and policy to address the problem.

Some state governments, environment groups and scientists have worked hard to develop feral cat control options, and the 2015 Australian Threatened Species Strategy did much to focus national attention and resourcing to the issue.

Read more:

Don't let them out: 15 ways to keep your indoor cat happy

The parliamentary inquiry is a major step forward, and many recommendations are sound. But overall, its recommendations call for incremental improvement.

Australia’s laws clearly fail to provide a safety net for wildlife. The cat issue is part of a larger problem with how we manage habitat, biodiversity and threats to nature – and fixing that requires wholesale change.

Authors: Sarah Legge, Professor, Australian National University