The viral ‘Wellerman’ sea shanty is also a window into the remarkable cross-cultural whaling history of Aotearoa New Zealand

- Written by Kate Stevens, Lecturer in History, University of Waikato

In a year of surprises, one of the more pleasant was the recent runaway viral popularity of 19th century sea shanties on TikTok. A collaborative global response to pandemic isolation, it saw singers and musicians layering harmonies atop an original recording of Soon May the Wellerman Come by Scottish postie Nathan Evans.

Spread via TokTok and other social media, it has become the most popular song in the “ShantyTok” trend. What many fans possibly didn’t realise at first, though, was that the Wellerman shanty is an old New Zealand composition.

More than that, it is a window into an earlier era of global interconnection that shaped the social and economic history of our southern coasts.

The lyrics speak of men’s collective labour at sea. But behind the story of the whale hunt is one of cross-cultural interaction central to the success of the whaling industry, and critical in shaping the settlement of early 19th century New Zealand.

Whaling in the 19th century world

Whaling brought newcomers to Aotearoa New Zealand in significant numbers from the early 1800s. Once predominantly American-based crews had exploited Atlantic whale populations, they moved into the Pacific to seek new hunting grounds.

These men sought profit in the form of oil and bone. Whale oil provided industrial lubrication and lighting for growing cities in Europe and the US. Baleen from whale jaws was used in much the way plastic is now.

New Zealand was one of their destinations. The Wellerman shanty refers to the heyday of whaling in the South Island. The Sydney-based Weller brothers established their first whaling station at Ōtākou (Otago) in 1831.

They and others such as Johnny Jones oversaw stations ranging from a few households to nearly 100 residents. These new settlements were dotted around the southern coasts from the late 1820s, often located near the paths of migrating right whales.

Read more: ShantyTok: is the sugar and rum line in Wellerman a reference to slavery?

Unlike deep-sea whaling in the Atlantic and northern Pacific, these newcomers practised shore-based whaling which required land to process the whales caught. The “tonguing” in the Wellerman lyrics refers to cutting strips of blubber to render into oil in large “try pots” — a challenging process aboard ship. The crew also required land on which to live and cultivate food.

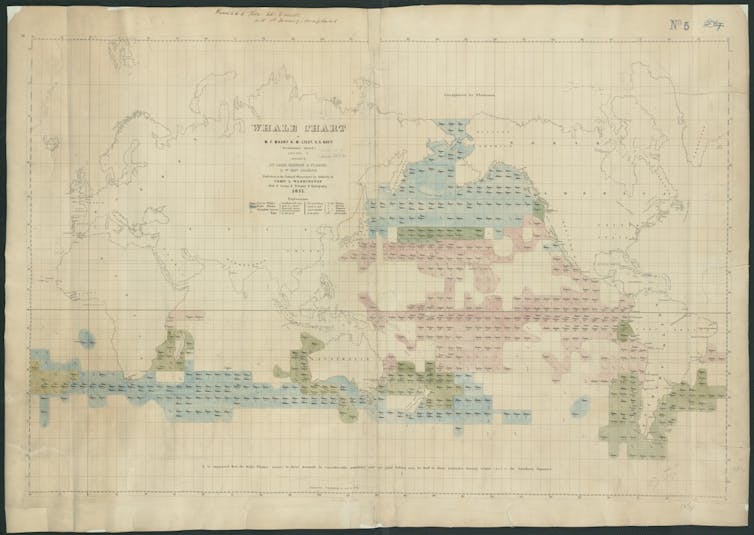

Map showing the distribution of whales across different seasons in the mid-19th century.

Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center, Boston Public Library, CC BY-SA

Map showing the distribution of whales across different seasons in the mid-19th century.

Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center, Boston Public Library, CC BY-SA

Whalers in the Ngāi Tahu world

These shore whalers entered a Māori world. The success of a station was dependent on their relationships with local iwi as tangata whenua — in this case, Ngāi Tahu.

Newcomers had to negotiate access to coastal land and resources, and stayed for months, years, sometimes even decades. Because the industry was based on settlement rather than short refuelling stops, shore whaling fostered more intensive cross-cultural interactions in southern New Zealand than elsewhere in New Zealand or abroad.

Differing cultural expectations and miscommunication occasionally led to violence. More often, however, Ngāi Tahu and newcomers negotiated a relationship of mutual benefit. Whaling connected Ngāi Tahu to the global economy in the early 19th century, providing new and sometimes mana-enhancing opportunities for trade, employment, and travel.

Read more: Rock art shows early contact with US whalers on Australia's remote northwest coast

At the same time, Ngāi Tahu communities sought to incorporate whaling men into the rights and responsibilities of whanaungatanga (relations, connectedness). Intimate relationships and marriage were key features of this process, as historian Angela Wanhalla has shown.

Over 140 men had married Māori women in southern New Zealand by 1840, with these couples producing over 500 children. Edward Weller himself married Paparu, daughter of Tahatu and Matua. After her early death, Weller remarried Nikuru, daughter of rangatira (chief) Taiaroa, but left New Zealand without his wife and daughters after the Otākou station’s closure in 1841.

Ngāi Tahu in the whaling world

Many whaling stations became kin-based economies, with mixed families central to the labour and prosperity of both ship and station. As wives and partners, Ngāi Tahu women produced the food that sustained the station and supplemented the business of whaling.

While the Wellerman shanty’s “sugar and tea and rum” were imported as rations, potatoes, flax and pigs were locally produced, consumed, and exported for profit alongside whale oil and bone. Male relations also frequently worked in the industry, either on shore or as whaling crew.

A man’s world: whalers’ base on Stewart Island, 1924.

Te Papa

A man’s world: whalers’ base on Stewart Island, 1924.

Te Papa

Marriage also provided newcomers with access and ties to the land through their Ngāi Tahu whānau. Whaling captain John Howell’s first marriage to Kohikohi, the daughter of rangatira Horomona Patu, gave him access to 50,000 acres near Riverton.

This right to land for stations and settlement was based on principles of kaitiakitanga (guardianship). But in later decades the colonial government caused land dispossession through conversion to individual titles and Crown purchases.

Read more: Why it's time for New Zealanders to learn more about their own country's history

As the whaling industry declined from the 1840s, some whalers (like Edward Weller) proved transient visitors. Many others, like Howell, remained with their families, though most were not as wealthy.

Former whalers turned to fisheries, agriculture and trade. Their mixed communities formed the basis for settlements around the southern region: Bluff, Riverton, Moeraki, Taieri, Waikouaiti.

These early and intense interactions had a lasting legacy in Ngāi Tahu’s whakapapa (genealogy) and collective identity. The sustained contact between Ngāi Tahu and whalers also complicates the myth of whaling as simply a transient and masculine pursuit.

Whaling was indeed a gendered industry; crew were almost exclusively male. But they were also diverse. Native American, Aboriginal Australian and Pacific Islanders all found opportunities aboard ship and in New Zealand alongside Māori and Europeans.

Many of them, we must assume, would have sung or heard shanties like Soon May the Wellerman Come — though none might have expected their descendents in the 21st century to be humming them too.

Authors: Kate Stevens, Lecturer in History, University of Waikato