Ancient stories and enduring spirit: Loving Country reminds us of the wonders right under our noses

- Written by Shannon Foster, D'harawal Knowledge Keeper PhD Candidate and Lecturer UTS, University of Technology Sydney

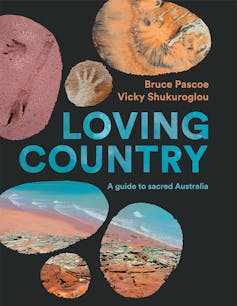

Review: Loving Country by Bruce Pascoe and Vicky Shukuroglou (Hardie Grant Travel)

Travelling through the Australian landscape is an often breathtaking experience raising many questions in the traveller’s mind — none of which can be answered by an online search engine when your internet connection fails.

What everyone needs is a travel companion like Loving Country, co-authored by Aboriginal Elder Bruce Pascoe and artist Vicky Shukuroglou. At first glance, it is a travel guide to some of Australia’s most beautiful Country but on closer inspection, it reveals honest, riveting yarns about the true stories of Country told by the people who know her best: the local Aboriginal people with ancestral connections.

Bruce Pascoe.

Linsey Rendell

Bruce Pascoe.

Linsey Rendell

In Loving Country, the pair travel across the continent visiting 19 locations including Bruny Island in Tasmania, the Western Desert region, Margaret River, Alice Springs, Broome and Kangaroo Island.

Connecting with local Aboriginal people sounds common sense but in so many instances, visitors will grab the closest Aboriginal person, even if they are not from the area, and with a “you’ll do” mentality, recklessly erase local knowledges.

Loving Country highlights the inadequacy and tokenism of this “tick-a-box” approach, as it tells the rich and complex stories of local Aboriginal peoples and their unique understanding of Country, born of thousands of generations connected to place.

In Wiluna, at the edge of the Western Desert, the local Martu ladies love a yarn, telling ancient stories as readily as they share the contemporary love story of Warri and Yatungka, a couple who fell in love despite their relationship being forbidden by tribal laws. In Queensland’s Laura Basin, local Indigenous rangers and Elders share their living culture, teaching the young ones how to catch cherabin (yabbie).

The generosity of custodians and storytellers at each location is what makes Loving Country unique. The book also provides invaluable information on how to connect with local people and knowledge: a necessity for meaningful experiences with Country and culture.

Mparntwe (Alice Springs) in the heart of Australia, roughly 1500 kilometres south of Darwin. Arrernte language group.

Photographer: © Vicky Shukuroglou taken from Loving Country by Bruce Pascoe and Vicky Shukuroglou

Mparntwe (Alice Springs) in the heart of Australia, roughly 1500 kilometres south of Darwin. Arrernte language group.

Photographer: © Vicky Shukuroglou taken from Loving Country by Bruce Pascoe and Vicky Shukuroglou

Complex and nuanced

Loving Country consistently reiterates that Aboriginal cultures are as complex and nuanced as the Country we call “Mother”. The subtext here is that there is no pan-Aboriginality.

In any given place it is not one people, one place, one language. Single ownership is founded in the Eurocentric possession of land and resources — a colonial imposition on the complex kinship systems of Indigenous cultures and their approaches to care and custodianship of Country.

Loving Country will be important for Aboriginal people connected to a common body of Country but who come from multiple nation and clan groups. For others, if you are hearing just one group name, please look beyond it and take the time to find out if there are others. You will find contradictions, ambiguities and inconsistencies but that’s OK. Embrace them all. Country means different things to different people but it will always be the one uniting force between us.

Read more:

Friday essay: this grandmother tree connects me to Country. I cried when I saw her burned

My only disappointment in the book was that Country was not capitalised. For Aboriginal people, the word Country is a proper noun, a name for the spiritual entity we understand her to be. Country does not just describe the physical landscape as it would for others. Country is our mother, we do not own her, we belong to her.

Rage and frustration

In Australia, we collectively idolise overseas tourist destinations for their apparent “antiquity”. Loving Country points out that as a nation, we give heritage listing to fence wire and bronze memorials to genocidal murderers. We then destroy sacred sites containing evidence of Aboriginal culture tens of thousands of years old.

Read more:

Juukan Gorge: how could they not have known? (And how can we be sure they will in future?)

Pascoe’s rage and frustration at Australia’s ambivalence towards the astounding Country and culture right under our noses is palpable.

He writes that Moyjil (Point Ritchie) in Warrnambool, for instance, has memorials to colonial heritage and agriculture, the success of which relied heavily on the exquisitely fertile soils created and managed by Aboriginal communities for millennia prior.

The local Gunditjmara people have always spoken of an ancient site on the Hopkins River. Pascoe describes recent research undertaken on the blackened stones of an ancient hearth there providing evidence of human occupation for 80,000 years.

In any given place it is not one people, one place, one language. Single ownership is founded in the Eurocentric possession of land and resources — a colonial imposition on the complex kinship systems of Indigenous cultures and their approaches to care and custodianship of Country.

Loving Country will be important for Aboriginal people connected to a common body of Country but who come from multiple nation and clan groups. For others, if you are hearing just one group name, please look beyond it and take the time to find out if there are others. You will find contradictions, ambiguities and inconsistencies but that’s OK. Embrace them all. Country means different things to different people but it will always be the one uniting force between us.

Read more:

Friday essay: this grandmother tree connects me to Country. I cried when I saw her burned

My only disappointment in the book was that Country was not capitalised. For Aboriginal people, the word Country is a proper noun, a name for the spiritual entity we understand her to be. Country does not just describe the physical landscape as it would for others. Country is our mother, we do not own her, we belong to her.

Rage and frustration

In Australia, we collectively idolise overseas tourist destinations for their apparent “antiquity”. Loving Country points out that as a nation, we give heritage listing to fence wire and bronze memorials to genocidal murderers. We then destroy sacred sites containing evidence of Aboriginal culture tens of thousands of years old.

Read more:

Juukan Gorge: how could they not have known? (And how can we be sure they will in future?)

Pascoe’s rage and frustration at Australia’s ambivalence towards the astounding Country and culture right under our noses is palpable.

He writes that Moyjil (Point Ritchie) in Warrnambool, for instance, has memorials to colonial heritage and agriculture, the success of which relied heavily on the exquisitely fertile soils created and managed by Aboriginal communities for millennia prior.

The local Gunditjmara people have always spoken of an ancient site on the Hopkins River. Pascoe describes recent research undertaken on the blackened stones of an ancient hearth there providing evidence of human occupation for 80,000 years.

Brewarrina on the banks of the Barwon River in north-west New South Wales. Ngemba, Murrawarri, Yuwaalaraay, Wayilwan Language groups.

Photographer: © Vicky Shukuroglou taken from Loving Country by Bruce Pascoe and Vicky Shukuroglou

In Brewarrina, north-west New South Wales, 40,000-year-old stone fish traps are, he writes, “arguably the oldest human construction on earth”.

Just 80kms south-east, in Cuddie Springs, writes Pascoe, a stone dish was being used to grind grain for bread 35,000 years ago. Soon after this find, he notes, a seed-grinding stone was found in Arnhem Land, dated at 65,000 years old.

Read more:

Friday essay: Dark Emu and the blindness of Australian agriculture

Loving Country reveals page after page of both the ancient and contemporary knowledges of these magnificent places, leaving you feeling equal parts wonder and despair. It is a beautifully composed, riveting read scaffolded by Pascoe’s signature commitment to watertight research of the colonial archives.

Shukuroglou’s unpretentious photography showcases the raw, intrinsic beauty of Country. This book will leave you famished for red earth, rainforests, billabongs and big sky Country.

By all means, revel in these far off and dreamy locations but please keep in mind, Sacred Country is everywhere. It doesn’t matter how much concrete, glass or steel you lay down, Country is still here. Her ancient stories and enduring spirit live on in the hearts of local Aboriginal people across the continent.

Brewarrina on the banks of the Barwon River in north-west New South Wales. Ngemba, Murrawarri, Yuwaalaraay, Wayilwan Language groups.

Photographer: © Vicky Shukuroglou taken from Loving Country by Bruce Pascoe and Vicky Shukuroglou

In Brewarrina, north-west New South Wales, 40,000-year-old stone fish traps are, he writes, “arguably the oldest human construction on earth”.

Just 80kms south-east, in Cuddie Springs, writes Pascoe, a stone dish was being used to grind grain for bread 35,000 years ago. Soon after this find, he notes, a seed-grinding stone was found in Arnhem Land, dated at 65,000 years old.

Read more:

Friday essay: Dark Emu and the blindness of Australian agriculture

Loving Country reveals page after page of both the ancient and contemporary knowledges of these magnificent places, leaving you feeling equal parts wonder and despair. It is a beautifully composed, riveting read scaffolded by Pascoe’s signature commitment to watertight research of the colonial archives.

Shukuroglou’s unpretentious photography showcases the raw, intrinsic beauty of Country. This book will leave you famished for red earth, rainforests, billabongs and big sky Country.

By all means, revel in these far off and dreamy locations but please keep in mind, Sacred Country is everywhere. It doesn’t matter how much concrete, glass or steel you lay down, Country is still here. Her ancient stories and enduring spirit live on in the hearts of local Aboriginal people across the continent.

Authors: Shannon Foster, D'harawal Knowledge Keeper PhD Candidate and Lecturer UTS, University of Technology Sydney