Not all blackened landscapes are bad. We must learn to love the right kind

- Written by Claire Smith, Professor of Archaeology, College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, Flinders University

The devastation wrought by last summer’s unprecedented bushfires created blackened landscapes across Australia. New life is sprouting, but with fires burning again in New South Wales and Queensland we have once more seen burnt land and smoke plumes.

The findings of the Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements are a reminder that we need to change our approach to bushfire management. One way of doing so is by rethinking the notion of a blackened landscape, embracing the positive qualities of contained fires.

Learning to love blackened earth will not be easy. It involves a fundamental change in aesthetic values — thinking through prejudices often attached to the colours of black and white.

‘Nice and clean’

When we were conducting fieldwork with Phyllis Wiynjorroc, the senior traditional owner at Barunga, Northern Territory, in 2005 we came across some country that had been burnt off by traditional firing.

Phyllis commented that it was “nice and clean”. To her eyes, a blackened landscape is pristine and beautiful.

Read more: Our land is burning, and western science does not have all the answers

Such landscapes are valued in many parts of the world. A darkened land can be valued because it is rich in humus. Amazonian Dark Darths, for instance, (also known as Indian black earth) are known for their fertility.

In sub-Saharan Africa, meanwhile, local people strategically enrich nutrient-poor soils to produce highly productive African Dark Earth.

Phyllis Wiynjorroc with her grandchildren Teagan and Joel at Barunga, Northern Territory.

Claire Smith, Author provided

Phyllis Wiynjorroc with her grandchildren Teagan and Joel at Barunga, Northern Territory.

Claire Smith, Author provided

As others have observed, Indigenous wisdom could help prevent Australian bushfires. Aboriginal cultural burning is low-intensity. Fires burn in a mosaic pattern (like a chessboard), allowing animals to move between areas. Afterwards, the burnt hollows of trees provide homes for selected animal species and some plants regenerate.

Aboriginal people, anthropologists and archaeologists have called for a return to cultural burning practices. Authorities also conduct controlled burning, with debatable sucess. We need more research on these aspects of Indigenous and Western science.

Read more: Strength from perpetual grief: how Aboriginal people experience the bushfire crisis

Concepts of colour

We see colour not only through a cultural lens but also through our own embodiment. A white-skinned tourist once told us that the landscape after a reduction burn looked black and dirty. She was so repulsed that she planned to make representations to politicians to ban such burns. This contrasts to the aesthetics of Aboriginal land management practices.

Non-Indigenous people typically connect the colour black with danger and bad things, while white is associated with purity and good things. This is obviously not the case for Aboriginal people.

Read more: Languages don't all have the same number of terms for colors – scientists have a new theory why

Many Indigenous people (including the Aboriginal author of this article) find phrases like “Black Saturday” offensive. If the recent bushfire season had been dubbed “Australia’s White Devil”, it might have been similarly offensive to non-Indigenous people.

The challenge ahead will be to rethink our assumptions and create new, positive ways to think about the black colours of a burnt landscape.

Aesthetics and identity

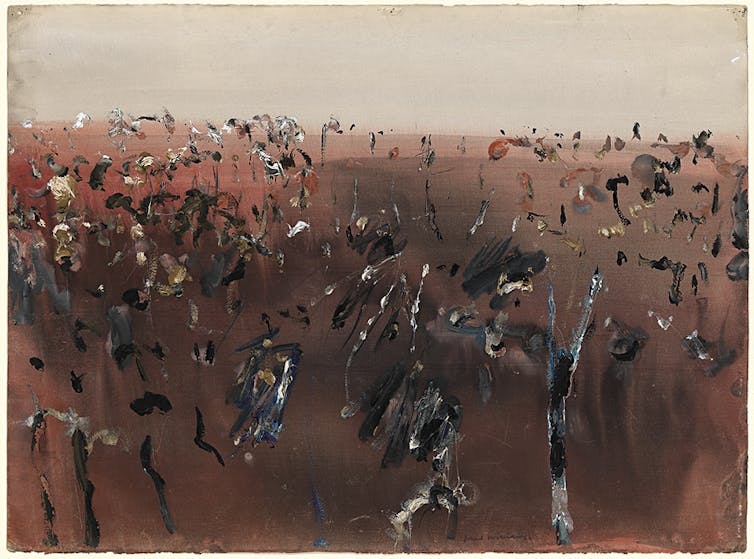

An Australian identity for the 21st century will need to embrace new understandings of our landscapes. One artist who grappled with the aesthetics of bushfire landscapes was Fred Williams (1927-1982). His celebrated bushfire series was prompted by a fire that stopped 100 metres short of his home in February 1968. This experience fundamentally altered Williams’ vision of the Australian landscape.

Fred Williams.

After bushfire (1) 1968

gouache

57.0 x 76.6 cm (image and sheet)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased through The Art Foundation of Victoria with the assistance of the H. J. Heinz II Charitable and Family Trust, Governor, and the Utah Foundation, Fellow, 1980 (AC9-1980)

© Estate of Fred Williams

Fred Williams.

After bushfire (1) 1968

gouache

57.0 x 76.6 cm (image and sheet)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased through The Art Foundation of Victoria with the assistance of the H. J. Heinz II Charitable and Family Trust, Governor, and the Utah Foundation, Fellow, 1980 (AC9-1980)

© Estate of Fred Williams

His groundbreaking artistic response was a detailed and repeated focus on burnt land that helped reshape Australian perceptions of bushfire. As writer John Schauble has noted, the series contains depictions of “the fire itself, the burnt landscape, those dealing with a single burning tree and the fern diptych”.

Williams, he has written, “examines not just the forest as a whole, but the minutiae of its rebirth, depicting individual plants as well as sweeping landscapes”.

Like Williams, we will have to alter our appreciation of what an Australian environment looks like.

Where there is smoke …

Rethinking our cultural appreciation of fire as we explore links between bushfires and climate change, will also require a reappraisal of smoke.

As David Bowman states in Australian Rainforests: Islands of Green in a Land of Fire, “Living in the bush means learning to live with fire”. The gum tree naturally drops leaves and small branches. It annually sheds bark. Throughout Australia, this provides the fuel that makes fires and smoke almost inevitable.

There are many kinds of smoke. There is the unwelcome smoke of last fire season, which clouded Australian cities and towns, lapped the globe, and was visible from space.

Ngarrindjeri Elder, Major Sumner, conducting an Australian Aboriginal smoking ceremony, part of the repatriation of ancestral human remains from the United Kingdom. 19 May, 2009.

Flickr, CC BY

Ngarrindjeri Elder, Major Sumner, conducting an Australian Aboriginal smoking ceremony, part of the repatriation of ancestral human remains from the United Kingdom. 19 May, 2009.

Flickr, CC BY

Then there is smoke from contained fires. Smoking ceremonies have been a part of Aboriginal cultural practices for centuries, if not millennia. Ngarrindjeri Elder, Major Sumner, uses smoke as part of the ceremonies associated with the repatriation of human remains. Smoke may be used in Welcome to Country ceremonies and at the opening of Aboriginal Studies Centres.

On Phyllis Wiynjorroc’s lands, Aboriginal women use smoke from burning selected leaves to protect newborn babies. Research has shown that traditional smoking techniques can produce smoke with significant antimicrobial effects.

Noticing

Monitoring when the landscape around us is blackened through the right kind of burning will help us become more aware of (and comfortable with) regular burning practices. We will also notice when such burning is needed.

After the bushfires on Kangaroo Island, South Australia, in February and cultural burning at Barunga, Northern Territory.

Amanda Whitrod & Claire Smith, Author provided (No reuse)

After the bushfires on Kangaroo Island, South Australia, in February and cultural burning at Barunga, Northern Territory.

Amanda Whitrod & Claire Smith, Author provided (No reuse)

How we interpret colour is culturally conditioned and often unconscious. Negative connotations of the colour black have long been challenged.

Clearly, there is more than one form of blackened landscape. But if we can learn to love the right kind, we might be able to limit our experience of the other.

Authors: Claire Smith, Professor of Archaeology, College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, Flinders University