NSW wants to change rules on suspending and expelling students. How does it compare to other states?

- Written by Anna Sullivan, Associate Professor of Education, University of South Australia

The disability royal commission heard from experts last week on the disproportionate number of students with a disability who have been suspended or expelled from school for “problem behaviour”.

The commission’s public hearings come at the same time the NSW education department is receiving submissions on a new behaviour management strategy. This plan, among other things, would see the maximum number of days students can be suspended for cut from 20 to ten.

The strategy was designed after inquiries showed too many suspensions being given to students who have a disability, are Indigenous, experience socioeconomic disadvantage, are in out-of-home care, and live in remote and regional areas.

In 2019, more than 113,000 students across Australia were removed from government schools, either for a set period or permanently — representing 4.3% of all government school enrolments. This figure is based on the limited data released by state and territory education departments. The true number is likely higher.

So, what are the rules around suspensions and expulsions in NSW, and the rest of Australia? And what needs to be done to reduce discrimination?

Different rules for different states

Schools use suspensions and expulsions to help change unproductive student behaviours, and allow time for other strategies to be implemented, to help avoid repeat situations.

Each state and territory has its own legislation (except NSW, which has a policy) that defines and guides the use of expulsions and suspensions.

The length of time students can be suspended for varies between states. For instance, a student in Queensland (and NSW under current legislation) can be suspended for up to 20 days. But in WA, the maximum is ten, and the school needs approval from the education department if it wants to extend it.

Suspensions in Victoria can generally be given for up to five days, but this can be extended to 15 with education department approval.

Each state also provides different grounds on which schools can suspend or expel students. In Queensland and Tasmania, a student can be suspended for disobedience or misbehaviour. Whereas in Victoria, a student has to “consistently behave in an unproductive manner that interferes with the well-being, safety or educational opportunities of any other student”.

Read more: Why suspending or expelling students often does more harm than good

In South Australia, a student can be expelled for similar behaviour to Victoria — for “persistently interfering with the ability of a teacher to instruct students or of a student to benefit from that instruction”. But an SA student can also be suspended for “persistent and wilful inattention or indifference to school work”.

Under the proposed changes in NSW, a school can only expel a student in kindergarten (the first year of school) to Year 2 for serious violence or possession of a weapon. And the maximums days a student in these year levels can be suspended would be reduced from 20 to five.

For students in Years 3 to 12, the maximum days for suspensions would be reduced from 20 to ten.

Problems with suspending or expelling kids

Children with disability aren’t the only group excluded from school more than others. Data from South Australia and Victoria show male students accounted for three-quarters of all suspensions and expulsions in 2019.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students also receive disproportionately more suspensions and expulsions than non-Indigenous students. In Queensland, Indigenous students accounted for 10% of all state school enrolments in 2019, but they made up 25% of all suspensions. And 25% of all students expelled in the state were Indigenous, too.

Research consistently shows removing children from school is not the best way to manage behaviour. It fails to address the underlying cause, and can often exacerbate the problem. An analysis of several studies conducted mainly in the US found suspensions are associated with poor academic achievement and dropout.

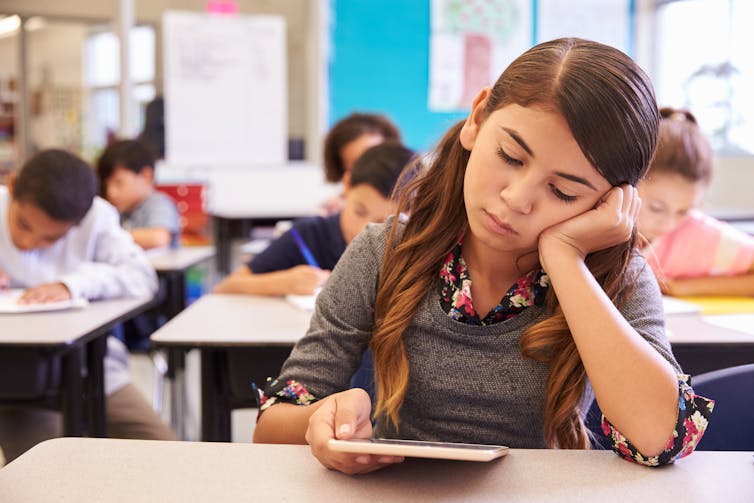

Removing students from school for indifference or inattention is unlikely to promote greater engagement. Research indicates suspensions exacerbate disengagement.

Removing a disengaged student from school will likely only exacerbate the problem.

Shutterstock

Removing a disengaged student from school will likely only exacerbate the problem.

Shutterstock

Within 12 months of being suspended from schools, students are 50% more likely to engage in anti-social behaviour and 70% more likely to engage in violent behaviour. In the US, many students who have been suspended or excluded from school end up in the juvenile justice system.

What needs to be done

Suspending or expelling a student should be considered a last resort. In determining whether to remove a student, principals should first investigate whether other issues could be impacting their behaviour.

They should also prepare a plan to support students and minimise repeat behaviours. This could include supporting the teacher, teaching the student social skills, providing them with literacy support and offering counselling.

The NSW proposal does encourage principals to first consider alternative strategies such as preparing a prevention and intervention plan, professional learning for staff and conflict resolution. But the proposal has gaps in other areas.

Children and their parents/guardians have a right to procedural fairness which means giving them opportunity to be heard before a decision is made and ensuring the decision-maker is impartial. The NSW proposal doesn’t include this.

Victoria’s legislation has the most comprehensive expectations for procedural fairness which include the opportunity to be heard and considering other forms of action that could address the behaviour for which the student is being suspended.

Most states also include an appeal process (through the school or education department) for expulsions. Queensland and the ACT have an appeal process for suspensions. But the NSW proposal does not include an appeal process for suspensions or expulsions.

Schools should develop a plan that outlines educational support during the students’ absence, so they can continue their education. In the case of expulsion, a principal must take reasonable steps to arrange for access to an educational program that allows the student to continue their education.

The NSW plan includes this expectation. Queensland, Western Australia, Victoria, ACT and Tasmania have similar requirements.

And finally, a school should outline how it will support a successful transition back for a suspended student. This could include reintegration meetings with parents, children and other service agencies, and a phased re-introduction into the school.

The NSW proposal commits to improved guidance on reintegration, but few details are given on how it would go about doing this. It is important schools develop such a plan in consultation with the student and their parents.

Authors: Anna Sullivan, Associate Professor of Education, University of South Australia