We need to restart immigration quickly to drive economic growth. Here's one way to do it safely

- Written by Anna Boucher, Associate Professor in Public Policy and Political Science, University of Sydney

Faced with a difficult economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, Australia needs to act quickly with creative solutions to reestablish immigration into the country, even before a potential vaccine is found.

Over the past two decades, population growth has been an important driver of Australia’s economic growth. Immigration is the largest component of this, comprising about 64% of our population growth in 2016-17 (with the rest coming from natural increase).

This year, immigration is down because of COVID-19, but also because of reductions in permanent migration numbers set by the government for 2019-20. Immigration levels will be low well into 2021, with net overseas migration expected to be -72,000 (from previous highs near 300,000).

This is the first time since the second world war it has fallen to negative levels.

According to last week’s budget, Australia’s overall population growth is expected to be just 0.2% in 2020-21 and 0.4% in 2021-22, the slowest growth in over a century.

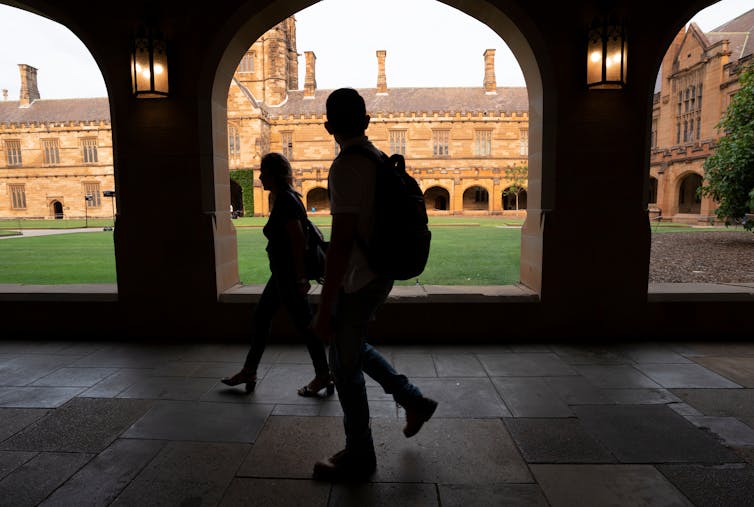

The university sector faces up to A$19 billion in losses over the next three years due to lost international student revenue.

Shutterstock

The university sector faces up to A$19 billion in losses over the next three years due to lost international student revenue.

Shutterstock

Why immigration is so vital to the economy

The border closure is devastating for people trying to come to Australia, whether they are migrants wishing to start a new life, refugees or in some cases, even partners of those already living in the country.

However, aside from these important human stories, the immigration downturn will also have considerable economic effects.

Read more: How universities came to rely on international students

First, as mentioned before, immigration growth drives economic growth. And a return to over 3% economic growth without immigration seems unlikely. When we take into consideration lower fertility rates during the pandemic, such growth is even less likely.

Lower immigration has a real effect on GDP. In the June quarter of 2020, GDP contracted by 7%, which is the largest fall on record. At least some of this is due to plummeting immigration.

Second, the continued border closure affects our key exports, in particular international student arrivals. Total exports are predicted to fall 9% in the next year, while net exports are expected to shave 1 percentage point from GDP growth in 2021-22. International student migration and tourism make up a large part of these exports.

For some Australian universities, international students make up around 30-40% of total revenue.

Shutterstock

For some Australian universities, international students make up around 30-40% of total revenue.

Shutterstock

Third, lower immigration rates affect levels of consumption. With one million fewer people entering Australia this year, there will be less demand for services and housing. This is leading to urgent calls for a return to immigration from within the construction sector.

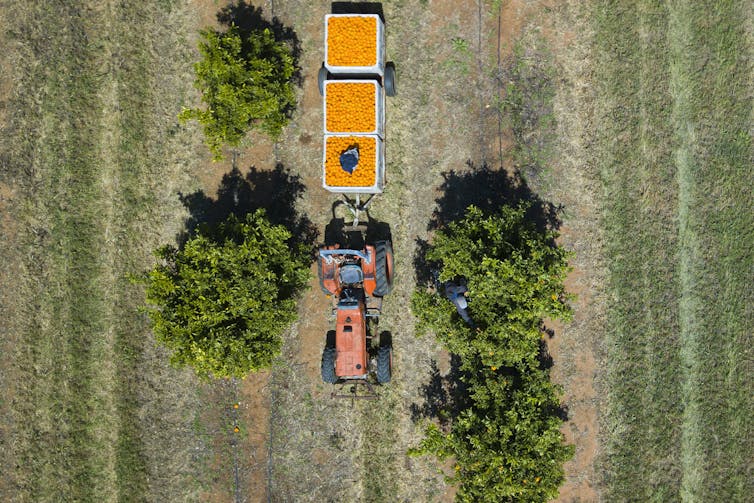

Fourth, lower immigration rates may cause critical problems for the labour market in certain industries. Much of the horticulture and agriculture sector, for instance, was previously supported by working holiday makers. Farmers are now desperate for assistance, with a projected labour shortfall for summer harvests estimated to be 26,000 workers.

Attempts to mobilise Australian workers into these jobs have been largely unsuccessful, in part due to the low wages, but also the regional nature of the work that would demand seasonal relocation.

The demand for seasonal workers to harvest produce will peak in March.

Lukas Coch/AAP

The demand for seasonal workers to harvest produce will peak in March.

Lukas Coch/AAP

Fifth, fewer immigrants results in fewer people of working age contributing to the tax base. Many immigrants are generally under 45 and are here to work — either in skilled jobs or on working holiday visas. Losing large numbers of them means fewer people of working age in the population.

Of course, this assumes these people would be working during COVID-19. Research suggests temporary migrants are experiencing high rates of unemployment and homelessness during the pandemic, meaning they may not be working and contributing taxes as they normally would.

Still, given they are not receiving welfare assistance or Medicare, they are placing less strain on public systems than Australian citizens and permanent residents.

And unemployment is not a long-term problem. As the economy recovers, the hospitality sector is expected to bounce back quickly, with many temporary migrants able to return to work.

How we can restart immigration with user-pay quarantine

Last week’s budget suggested the government will start experimenting with immigration corridors (bringing in small numbers of migrants from selected countries) in late 2020, but it does not anticipate immigration will be back to normal until well into 2021. This would also be dependent on the discovery and development of a vaccine.

The economic challenges we are facing are a strong incentive for the government to find creative solutions to bring immigrants back to Australia quickly at previous levels.

In an interview this week, Immigration Minister Alan Tudge said

the quarantine system is the speed limit […] And obviously there’s only a certain number of slots available there.

But there are many hotels that are failing to attract visitors and are desperate for business, and would be happy to engage in quarantining.

User-pay quarantine with a robust security guard system is a feasible solution that would allow the economy to get back on track and keep Australia safe from COVID-19 spread.

The current hotel quarantine system could be expanded to restart immigration.

DAN HIMBRECHTS/AAP

The current hotel quarantine system could be expanded to restart immigration.

DAN HIMBRECHTS/AAP

Here is how it would work. Immigrants would be tested three days before leaving their home countries. They would not be allowed to board a flight if they are unwell. On arrival, they will be quarantined.

This could be in the Northern Territory or other remote parts of Australia, which would generate revenue for regional areas. NT already does this for people from Victoria, allowing them to quarantine there for 14 days before flying elsewhere in the country — charging them a pretty penny in the process.

Costs would be shared by workers or firms. This could be left to the market to sort out. Australian companies who really need workers will be willing to shoulder the lion’s share of the costs, while non-sponsored individuals could pay for themselves.

This doesn’t require a travel bubble. It doesn’t require a vaccine. It can be implemented today.

Read more: Another day, another hotel quarantine fail. So what can Australia learn from other countries?

Authors: Anna Boucher, Associate Professor in Public Policy and Political Science, University of Sydney