Morrison is right. All governments will need to spend more to get us out of the crisis

- Written by Danielle Wood, Chief executive officer, Grattan Institute

The prime minister wants the states to open their wallets. Although he has warned them not to “make whoopee”, his message is blunt: “The Commonwealth cannot do all the fiscal heavy lifting on its own”.

The Reserve Bank governor is more circumspect, but also says the states have an “important” role in the fiscal response to the COVID recession and “can do more over time”.

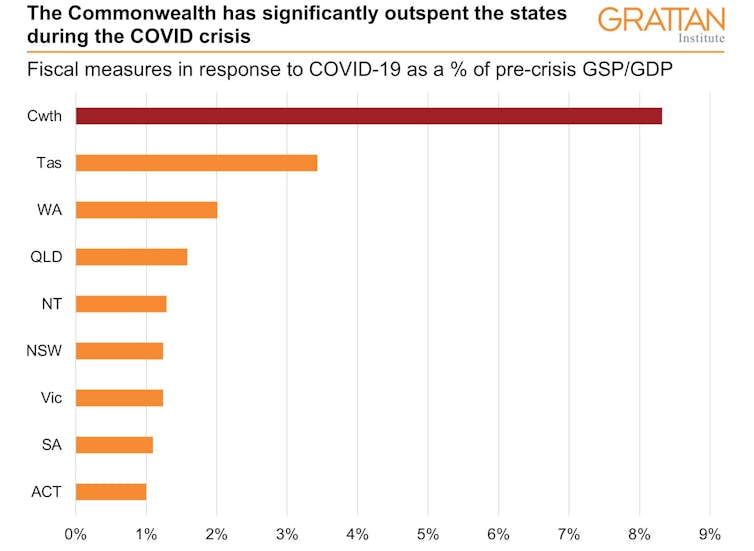

Have the states been slacking off? At first glance, it appears so. The Commonwealth’s stimulus contribution so far is more than A$170 billion, compared to less than A$30 billion from all of the state and territory governments.

To date, it’s the Feds more than the states

The Commonwealth has spent almost 9% of national output on stimulus, whereas no state except Tasmania has spent more than 2% of its own output.

The two biggest states, NSW and Victoria, have each spent little more than 1%.

But these measures tell only part of the story. The Commonwealth has greater spending power because it has more revenue to draw from, and the states get about half their revenue from the Commonwealth.

Source: Grattan analysis of government announcements

These disparities account for some of the unbalanced effort, but not all of it.

Excluding what it passes on to the states, the Commonwealth’s revenue as a share of gross domestic product is about twice that of most states as a share of gross state product.

Yet its COVID response has been almost six times as big.

Read more:

The big stimulus spending has just begun. Here's how to get it right, quickly

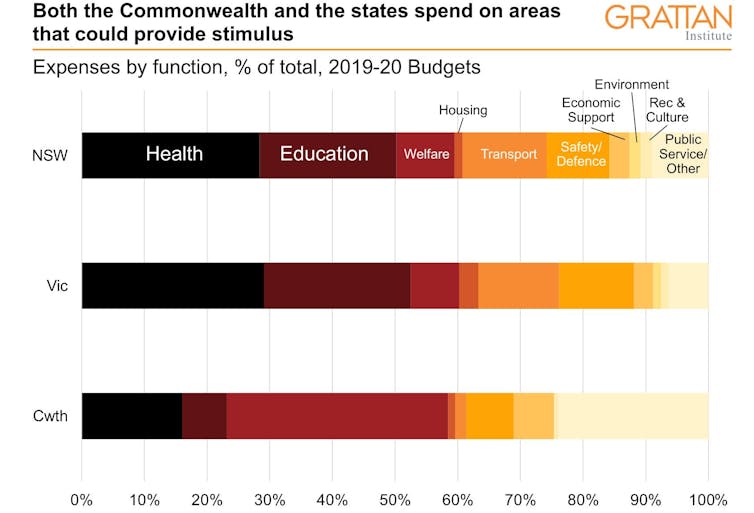

Although the Commonwealth is the main funder for several of the traditional stimulus levers – including the welfare and personal income tax systems – the states also spend money in areas that can be used to stimulate the economy.

The most important include social housing, health, education, and industry support.

Source: Grattan analysis of government announcements

These disparities account for some of the unbalanced effort, but not all of it.

Excluding what it passes on to the states, the Commonwealth’s revenue as a share of gross domestic product is about twice that of most states as a share of gross state product.

Yet its COVID response has been almost six times as big.

Read more:

The big stimulus spending has just begun. Here's how to get it right, quickly

Although the Commonwealth is the main funder for several of the traditional stimulus levers – including the welfare and personal income tax systems – the states also spend money in areas that can be used to stimulate the economy.

The most important include social housing, health, education, and industry support.

Notes: Commonwealth Budget (Budget Paper 1, Table 3, p5-7) does not specify funding for Environment, so this is included in other. ‘Economic Support’ for the Commonwealth includes spending on Fuel and energy; Agriculture, forestry and fishing; Mining,

manufacturing and construction; and Other economic affairs. Commonwealth figures include transfers to the states.

Source: 2019-20 Budget papers

There’s also plenty of “room to move” on state government balance sheets – all six states entered this crisis with net debt below 15% of gross state product and with interest and depreciation costs less than 2% of gross state product. All were projecting operating surpluses.

Their borrowing costs, though higher than the Commonwealth’s, are still exceptionally low.

NSW and Victoria can borrow for 10 years at an interest rate just over 1%, far below the Reserve Bank’s inflation target band, making the money free in real terms.

More is needed from both

All of this suggests our states can and should do more to support the recovery.

But the Commonwealth will also need to do more. Like the states, it has room to spend more, and it should.

The Reserve Bank expects unemployment to peak at 10% in the December quarter and still be as high as 7% in December 2022.

That’s too high for too long.

Read more:

Cutting unemployment will require an extra $70 to $90 billion in stimulus. Here’s why

To avoid this scenario, the Grattan Institute recommended in June that governments of both kinds plan for $70-to-$90 billion in extra stimulus over the next two years to bring unemployment down to 5% and get wages growing again.

The renewed economic fallout from State 4 restrictions in Melbourne means that the response will now need to be even larger.

There are many things governments can do beyond the extensions of JobKeeper and JobSeeker already announced.

A banquet of options

The Commonwealth could introduce a wage subsidy for new employees beyond March. And it should boost the childcare subsidy to help parents who have lost jobs or hours during the downturn to re-enter work.

It could also amplify state investments in infrastructure and services that create jobs and serve social needs: social housing and mental health services are obvious candidates. The tutoring program to help disadvantaged students that Grattan proposed in June also fits this bill.

Well-targeted personal income tax cuts or better, a tax bonus, targeted at low and middle income earners, can also help boost demand, including in worst-hit sectors such as hospitality, tourism, and the arts.

Read more:

No snapback: Reserve Bank no longer confident of quick bounce out of recession

But tax cuts generally don’t provide as much economic kicker as others forms of government stimulus because more of the money “leaks” to savings.

Announcing a permanent boost to JobSeeker beyond December would put money in the hands of those most likely to spend it.

Other ideas such as a temporary GST holiday or electronic vouchers to spend in certain sectors – an idea being adopted in Britain – have the advantage of being temporary and targeted.

There is a banquet of worthwhile options governments should be considering – and they shouldn’t fight over who picks up the tab.

If governments of both kinds don’t do more, the recession will last longer.

Maybe it wouldn’t hurt to make a little whoopee. The downside of doing too little way exceeds the potential downside of doing too much.

Notes: Commonwealth Budget (Budget Paper 1, Table 3, p5-7) does not specify funding for Environment, so this is included in other. ‘Economic Support’ for the Commonwealth includes spending on Fuel and energy; Agriculture, forestry and fishing; Mining,

manufacturing and construction; and Other economic affairs. Commonwealth figures include transfers to the states.

Source: 2019-20 Budget papers

There’s also plenty of “room to move” on state government balance sheets – all six states entered this crisis with net debt below 15% of gross state product and with interest and depreciation costs less than 2% of gross state product. All were projecting operating surpluses.

Their borrowing costs, though higher than the Commonwealth’s, are still exceptionally low.

NSW and Victoria can borrow for 10 years at an interest rate just over 1%, far below the Reserve Bank’s inflation target band, making the money free in real terms.

More is needed from both

All of this suggests our states can and should do more to support the recovery.

But the Commonwealth will also need to do more. Like the states, it has room to spend more, and it should.

The Reserve Bank expects unemployment to peak at 10% in the December quarter and still be as high as 7% in December 2022.

That’s too high for too long.

Read more:

Cutting unemployment will require an extra $70 to $90 billion in stimulus. Here’s why

To avoid this scenario, the Grattan Institute recommended in June that governments of both kinds plan for $70-to-$90 billion in extra stimulus over the next two years to bring unemployment down to 5% and get wages growing again.

The renewed economic fallout from State 4 restrictions in Melbourne means that the response will now need to be even larger.

There are many things governments can do beyond the extensions of JobKeeper and JobSeeker already announced.

A banquet of options

The Commonwealth could introduce a wage subsidy for new employees beyond March. And it should boost the childcare subsidy to help parents who have lost jobs or hours during the downturn to re-enter work.

It could also amplify state investments in infrastructure and services that create jobs and serve social needs: social housing and mental health services are obvious candidates. The tutoring program to help disadvantaged students that Grattan proposed in June also fits this bill.

Well-targeted personal income tax cuts or better, a tax bonus, targeted at low and middle income earners, can also help boost demand, including in worst-hit sectors such as hospitality, tourism, and the arts.

Read more:

No snapback: Reserve Bank no longer confident of quick bounce out of recession

But tax cuts generally don’t provide as much economic kicker as others forms of government stimulus because more of the money “leaks” to savings.

Announcing a permanent boost to JobSeeker beyond December would put money in the hands of those most likely to spend it.

Other ideas such as a temporary GST holiday or electronic vouchers to spend in certain sectors – an idea being adopted in Britain – have the advantage of being temporary and targeted.

There is a banquet of worthwhile options governments should be considering – and they shouldn’t fight over who picks up the tab.

If governments of both kinds don’t do more, the recession will last longer.

Maybe it wouldn’t hurt to make a little whoopee. The downside of doing too little way exceeds the potential downside of doing too much.

Authors: Danielle Wood, Chief executive officer, Grattan Institute