How Bob Brown taught Australians to talk about, and care for, the 'wilderness'

- Written by Libby Lester, Director, Institute for Social Change, University of Tasmania

The Conversation is running a series of explainers on key figures in Australian political history, looking at the way they changed the nature of debate, its impact then, and its relevance to politics today. You can also read the rest of our pieces here.

To understand Bob Brown’s impact on Australian political debate, watch Tasmanian commercial television and stay on the couch during the ad breaks.

Here’s an advertisement for “wilderness tours”, another for small businesses on the “Tarkine coast”. Few of the audience, let alone the businesses paying for the ads, would know these terms came into common use because of the way Bob Brown does politics.

Anywhere known as “wilderness” was best avoided before the late 1970s when Brown, then leader of the campaign to save Tasmania’s Franklin River from damming, started deliberately including the term in almost every public statement he made about the threatened area. He understood the symbolic power of the term.

His political and media opponents quickly learned also. The Hobart Mercury – a strong supporter of the Hydro Electric Commission and its political masters – rarely let the word onto its pages. This was different from, for example, the Melbourne Age, which opposed the damming.

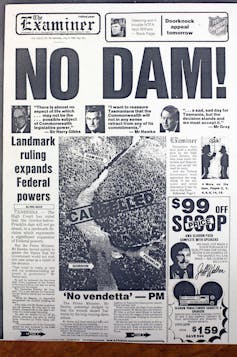

The High Court decision to block the Franklin River dam was very significant and divisive.

Tasmanian Electoral Commission

The High Court decision to block the Franklin River dam was very significant and divisive.

Tasmanian Electoral Commission

The Tasmanian media’s approach changed shortly after the High Court decision to block the damming in July 1983, when the commercial potential of “wilderness” began to emerge. Even the Mercury was promoting a calendar of “wilderness” images by the end of 1983.

Beginning in the 1990s, Brown applied the same patient strategy to the campaign to protect the area between the Arthur and Pieman rivers in north-west Tasmania. The Tarkine, with its forest and mineral resources, might still not be fully protected – earlier this year there were more arrests of members of the Bob Brown Foundation. But it is probably a lot closer than it would be if Brown had stuck to calling it the Arthur-Pieman.

Originally from regional New South Wales, Brown moved to Tasmania during the ultimately failed Lake Pedder campaign of the early 1970s. On the advice of Richard Jones, president of what is now recognised as the world’s first Green party, the United Tasmania Group, the openly gay young GP in ill-fitting suits started standing for Tasmanian parliament in 1972. After a decade of trying, he won the lower house seat of Denison (now renamed Clark; Brown might have come up with something less predictable) in 1983.

The shift from protest camps to the formal political arena proved challenging to Brown’s way of doing politics. As a young journalist covering Tasmanian parliament in the mid-1980s, I watched as the ever-polite-if-firm Brown inadvertently almost outlawed lesbianism as he tried to make Tasmania’s appalling anti-homosexuality laws symbolically nonsensical.

Ironically, the notoriously conservative members of the Legislative Council rejected his amendment, saving Tasmania’s lesbians from becoming criminals. While the mistake was memorable, more so was Brown’s willingness to acknowledge what he still describes as the worst moment of his political career.

However, some members of the Australian Greens, the party Brown was instrumental in forming in 1992, might suggest his worst political moment was publicly supporting the partial sale of Telstra in return for environmental gains before the party had debated the move internally.

Brown’s occasional failure to respect his party’s way of coming to decisions is forgivable. After all, consensus politics only really works when a strong leader guides the way, and Brown – as is increasingly obvious for the Greens – was exactly that.

Brown was elected to the Senate in 1996, after ten years in the lower house of Tasmania’s state parliament. He was re-elected to the Senate twice, in 2001 and again in 2007 when he won the highest personal vote of any Tasmanian senator.

The 2010 election resulted in nine Greens in the Senate and one in the House of Representatives. Negotiations with Brown and the Greens led to Julia Gillard and the ALP forming government in return for an ever-elusive carbon plan.

As a senator, Brown continued his play with the symbolic that he had learned so well as a protester. He made international headlines in 2003, not only for interjecting during US President George W. Bush’s speech to the Australian parliament, but for shaking the president’s hand afterwards. Bush responded to the heckling by saying: “I love free speech.”

Woodchip giant Gunns expressed exactly the opposite sentiment the following year when it launched a A$6.3 million law suit against Brown and 19 other activists just before Christmas to silence them over its pulp mill plans. Gunns should have known Brown was always going to out-survive it. The company collapsed in 2012, taking with it one of the worst reputations in Australian corporate history.

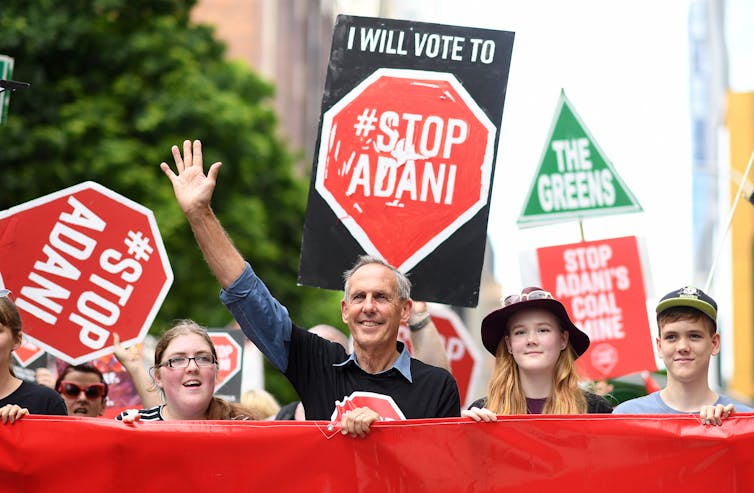

Brown stepped down as leader of the Australian Greens and retired from the Senate in 2012. After forming the Bob Brown Foundation, he has sparked more recent debate over whether the Adani convoy in 2019 was in fact his worst political moment, turning Queensland voters and thus the most recent federal election to the LNP.

For some critics, the convoy led by Brown was a misguided attempt to redeploy old tactics and relive past glories. Given the protest involved a convoy of fossil-fuelled vehicles travelling to oppose fossil fuel extraction, it does seem on the surface, at least, that Brown’s ability to harness the symbolic deserted him in this case.

Bob Brown continues to remain active in environmental causes, most recently as a leader of the #Stop Adani campaign.

Dave Hunt/AAP

Bob Brown continues to remain active in environmental causes, most recently as a leader of the #Stop Adani campaign.

Dave Hunt/AAP

However, a deeper play with the symbolic was under way, one I suspect Brown knows will be recognised with time, if it hasn’t been already. Brown is not afraid of being seen as an outsider – perhaps he has had no choice in a country where blokiness is a common character trait of political insiders. Nor has he ever pandered to the small-town politics that puts local rights over what he considers the greater good.

The Adani convoy was meant to be seen exactly as it was – an invasion by outsiders. If it contributed to the election loss for the ALP, so be it. Brown is playing a long game.

Brown may have affected the way politics is debated in Australia, but he has not yet changed that politics.

As Brown’s career has highlighted, ours is a politics where economic growth and environmental protection are still largely in conflict: jobs versus conservation, social needs versus ecological futures, left versus right. These tensions remain as evident in the political party Brown formed as in the responses of his political opponents, in media commentary and in voter choices.

Australia’s inability to act on carbon emissions exemplifies both the enduring nature of this politics and how long a game Brown has always been willing to play. In Brown’s maiden speech in the Senate in 1996, he said:

One has only to look again at the reality that if we do not rein in the greenhouse gas phenomenon one billion people on this planet will be displaced if the oceans rise by a metre at the end of the next century. This for a planet on which the wealthy ones who fly between here and London put, on average per passenger, five tonnes of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

Thirteen years later, when the Greens led by Brown voted against Labor’s Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme - and hence still carry the blame for Kevin Rudd’s failure to respond to “the greatest moral challenge of our time” - Brown’s argument for his party’s opposition to the scheme was “that it locked in failure” by “providing polluters billions of dollars and setting targets way too low”.

Like Gunns, the major parties can’t say they weren’t warned. Another thing Brown had said in his first speech in the Senate, quoting British environmentalist Jonathon Porritt, was: “the future will either be green or not at all”.

Brown is indeed playing a long game, and we can only guess what name he will give politics if he wins.

Authors: Libby Lester, Director, Institute for Social Change, University of Tasmania