We are what we steal: the New South Wales Police Gazette and charting histories of crime

- Written by Rachel Franks, Conjoint Fellow, School of Humanities and Social Science, University of Newcastle

In January 1788, a small floating society — eleven ships carrying crew, crooks, some military men and a few passengers — sailed into the body of water the colonisers called Port Jackson.

In the long term, there were ambitious plans for this new outpost of the British Empire. In the short term, this colony of thieves was all about crime and crime control; the details of which, from the mid-1800s, were published in what came to be known as the Police Gazette.

This fascinating record is the subject of a new online experience hosted by the State Library of New South Wales.

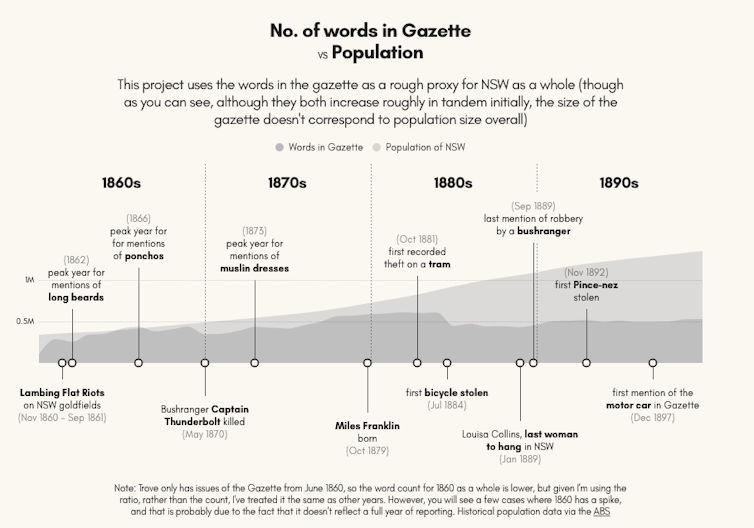

Sydney-based data visualisation designer and developer Brett Tweedie, has produced an extraordinary new data visualisation of almost 20 million words published in the Police Gazette from 1860 until 1900.

This new project, We Are What We Steal, was undertaken as a Digital Drop-In (a kind of small-scale Fellowship) at the State Library of New South Wales’ innovation unit, the DX Lab.

As this work shows, our desire for the details of crimes is nothing new. We see in the Police Gazette, and we see more clearly through Tweedie’s visualisations, the types of crime details that were important to capture in colonial New South Wales.

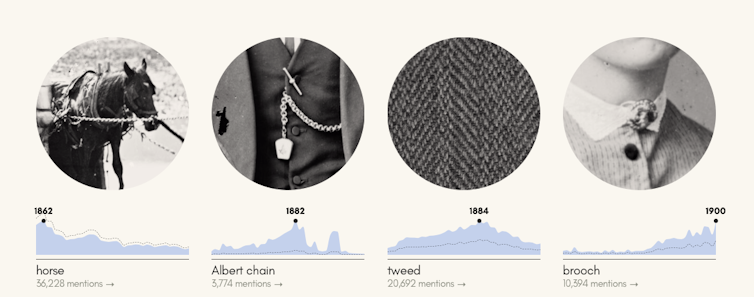

Horses, Albert Chains, Tweed and Brooches.

Brett Tweedie

Horses, Albert Chains, Tweed and Brooches.

Brett Tweedie

We Are What We Steal

Early efforts to police the colony

Australia’s first civilian police force, the Night Watch, was formed by Governor Arthur Phillip in 1789. This unit was made up of the 12 best-behaved convicts, who had been selected to assist in the keeping of law and order in Sydney Town.

It was not ideal to have convicts monitoring other convicts, but the marines stationed in the new colony were few. The military would supervise prisoners for certain purposes or tasks, but the work associated with constables and gaolers would have to be undertaken by others.

We Are What We Steal

Early efforts to police the colony

Australia’s first civilian police force, the Night Watch, was formed by Governor Arthur Phillip in 1789. This unit was made up of the 12 best-behaved convicts, who had been selected to assist in the keeping of law and order in Sydney Town.

It was not ideal to have convicts monitoring other convicts, but the marines stationed in the new colony were few. The military would supervise prisoners for certain purposes or tasks, but the work associated with constables and gaolers would have to be undertaken by others.

Botany Bay, New South Wales, ca 1789, by Charles Gore.

State Library of New South Wales

In 1796, the constables were reorganised by Governor John Hunter and divided into regions. Another reorganisation, ordered by Governor Lachlan Macquarie in 1810, resulted in a more formal, though still problematic, system of policing. The convict-as-constable model continued to reveal cracks in the system. Another effort to improve law enforcement was the Sydney Police Act 1833 (NSW) which was designed to regulate

the Police in the Town and Port of Sydney and for removing and preventing Nuisances and Obstructions therein.

Botany Bay, New South Wales, ca 1789, by Charles Gore.

State Library of New South Wales

In 1796, the constables were reorganised by Governor John Hunter and divided into regions. Another reorganisation, ordered by Governor Lachlan Macquarie in 1810, resulted in a more formal, though still problematic, system of policing. The convict-as-constable model continued to reveal cracks in the system. Another effort to improve law enforcement was the Sydney Police Act 1833 (NSW) which was designed to regulate

the Police in the Town and Port of Sydney and for removing and preventing Nuisances and Obstructions therein.

Sydney Cove, 1842, by O.W. Brierly.

State Library of New South Wales

Crime, of course, extended beyond the boundaries of Sydney. Containing lawbreakers in metropolitan and in regional and remote areas, was an ongoing issue for colonial authorities as the early crimes of insolence and petty thefts were placed into scale by more serious offences such as bushranging and murder.

One response to increases in crime was to establish specific types of police. There were various services across the colony, including the Row Boat Guard, the Border Police, the Mounted Police and the Gold Escort.

The Police Regulation Act 1862 (NSW) radically changed policing by amalgamating all the colonial police forces to establish the New South Wales Police Force.

Read more:

Enforcing assimilation, dismantling Aboriginal families: a history of police violence in Australia

The New South Wales Police Gazette

One of the most important tools of policing in colonial-era New South Wales was the Police Gazette. First published in 1854, as Reports of Crime, it was distributed to police stations across the colony.

Sydney Cove, 1842, by O.W. Brierly.

State Library of New South Wales

Crime, of course, extended beyond the boundaries of Sydney. Containing lawbreakers in metropolitan and in regional and remote areas, was an ongoing issue for colonial authorities as the early crimes of insolence and petty thefts were placed into scale by more serious offences such as bushranging and murder.

One response to increases in crime was to establish specific types of police. There were various services across the colony, including the Row Boat Guard, the Border Police, the Mounted Police and the Gold Escort.

The Police Regulation Act 1862 (NSW) radically changed policing by amalgamating all the colonial police forces to establish the New South Wales Police Force.

Read more:

Enforcing assimilation, dismantling Aboriginal families: a history of police violence in Australia

The New South Wales Police Gazette

One of the most important tools of policing in colonial-era New South Wales was the Police Gazette. First published in 1854, as Reports of Crime, it was distributed to police stations across the colony.

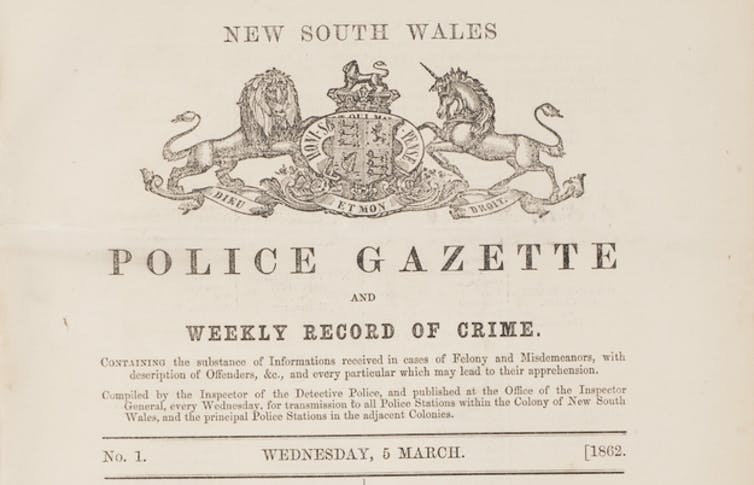

The New South Wales Police Gazette and Weekly Record of Crime.

State Library of New South Wales

These reports contained

details of crimes committed, persons to be apprehended, descriptions of stolen property and rewards offered, lists of regimental and ships deserters, and other police notices concerning recovery of property, apprehension of suspects previously sought, and dismissals of police officers for unsatisfactory conduct.

Published from 1862 as the New South Wales Police Gazette and Weekly Record of Crime, this vital tool for crime control became the Police Gazette in 1974 and appeared until 1982 (you can read issues of the Police Gazette, up to 1930, on Trove).

We are what we steal

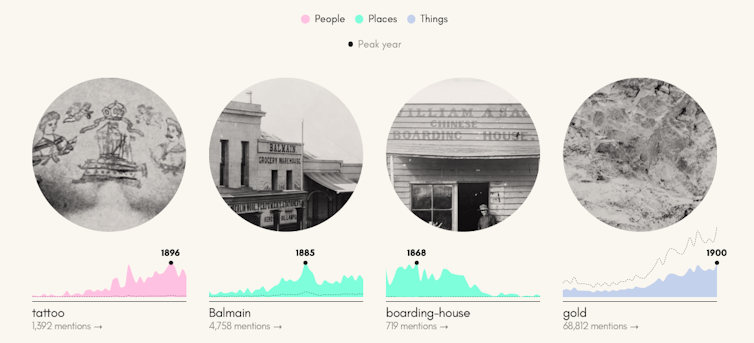

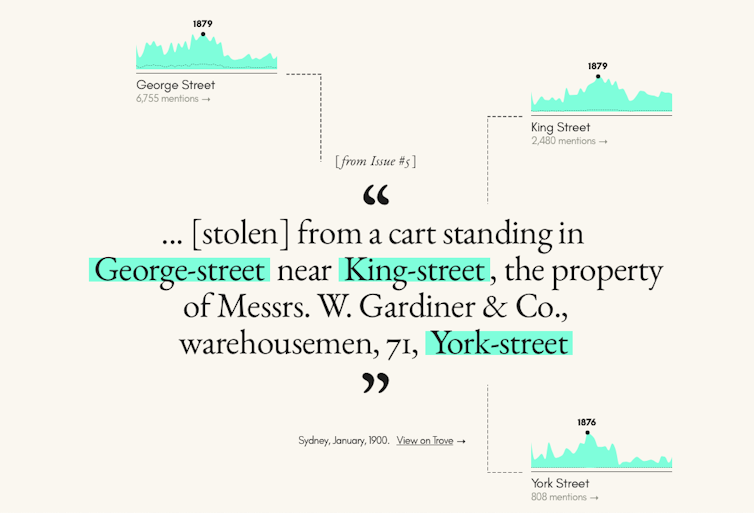

In We Are What We Steal, Tweedie has concentrated on people, places and things.

In this data visualisation, the men who captured details through the Police Gazette reveal themselves not just as constables on the lookout for criminals, but as storytellers.

The New South Wales Police Gazette and Weekly Record of Crime.

State Library of New South Wales

These reports contained

details of crimes committed, persons to be apprehended, descriptions of stolen property and rewards offered, lists of regimental and ships deserters, and other police notices concerning recovery of property, apprehension of suspects previously sought, and dismissals of police officers for unsatisfactory conduct.

Published from 1862 as the New South Wales Police Gazette and Weekly Record of Crime, this vital tool for crime control became the Police Gazette in 1974 and appeared until 1982 (you can read issues of the Police Gazette, up to 1930, on Trove).

We are what we steal

In We Are What We Steal, Tweedie has concentrated on people, places and things.

In this data visualisation, the men who captured details through the Police Gazette reveal themselves not just as constables on the lookout for criminals, but as storytellers.

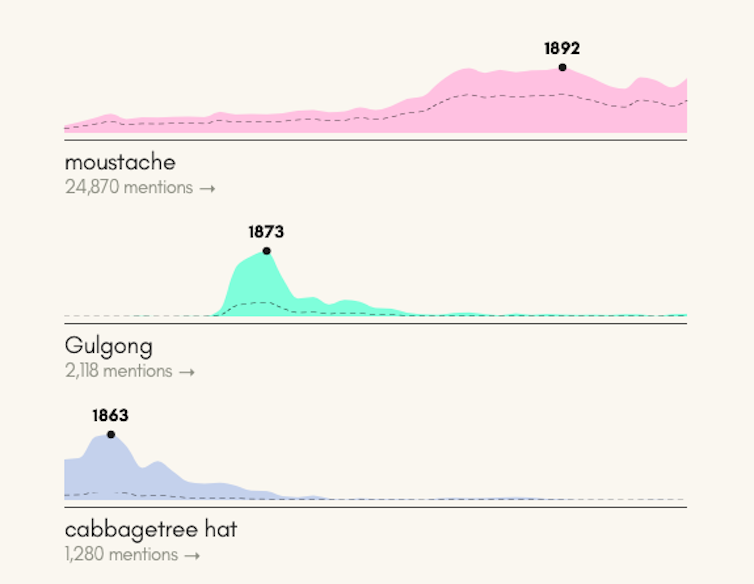

Mentions of moustaches, the 19th-century gold rush town Gulgong and cabbagetree hats.

Brett Tweedie

Favourite crime fiction authors and popular true crime writers often use stereotypes to serve as shorthand for their readers. Police officers also routinely relied on creating and using stereotypes to tell crime stories to each other.

Yet, stereotypes have severe consequences in the real world. In the case of the Police Gazette, a publication designed to make society safer could also make society more unequal through reinforcing common prejudices.

Crime is timeless and universal, but the contexts for crime are fluid. As Tweedie writes, we can see numerous stories in the Police Gazette, including:

Changing fashions, new technologies, new modes of transport, the establishment of new towns, increasing wealth, all this is recorded in the gazette — along with the racism of the day — as a by-product of reporting the crimes (and other police matters) that occurred.

Tweedie prompts us to interrogate crime by focusing on a single element of criminal acts. From age to gender and through to the drunken state of offenders. In a colony known for thieving, we can also look at what was stolen, from jewellery to clothing and, as times changed, bicycles.

Mentions of moustaches, the 19th-century gold rush town Gulgong and cabbagetree hats.

Brett Tweedie

Favourite crime fiction authors and popular true crime writers often use stereotypes to serve as shorthand for their readers. Police officers also routinely relied on creating and using stereotypes to tell crime stories to each other.

Yet, stereotypes have severe consequences in the real world. In the case of the Police Gazette, a publication designed to make society safer could also make society more unequal through reinforcing common prejudices.

Crime is timeless and universal, but the contexts for crime are fluid. As Tweedie writes, we can see numerous stories in the Police Gazette, including:

Changing fashions, new technologies, new modes of transport, the establishment of new towns, increasing wealth, all this is recorded in the gazette — along with the racism of the day — as a by-product of reporting the crimes (and other police matters) that occurred.

Tweedie prompts us to interrogate crime by focusing on a single element of criminal acts. From age to gender and through to the drunken state of offenders. In a colony known for thieving, we can also look at what was stolen, from jewellery to clothing and, as times changed, bicycles.

People, Places and Things.

Brett Tweedie

The history of policing reflects the values of a society and what, and who, is being protected.

Similarly, the stories of the men and women known to police in 19th-century New South Wales tell us, not just about crime, but about every aspect of society: who held power, who was vulnerable and how people lived.

People, Places and Things.

Brett Tweedie

The history of policing reflects the values of a society and what, and who, is being protected.

Similarly, the stories of the men and women known to police in 19th-century New South Wales tell us, not just about crime, but about every aspect of society: who held power, who was vulnerable and how people lived.

A case study of crime on the streets of Sydney’s central business district.

Brett Tweedie

Read more:

Whores, damned whores and female convicts: Why our history does early Australian colonial women a grave injustice

A case study of crime on the streets of Sydney’s central business district.

Brett Tweedie

Read more:

Whores, damned whores and female convicts: Why our history does early Australian colonial women a grave injustice

Authors: Rachel Franks, Conjoint Fellow, School of Humanities and Social Science, University of Newcastle