HomeBuilder only makes sense as a nod to Morrison's home-owning voter base

- Written by Lisa Adkins, Professor of Sociology and Head of School of Social and Political Sciences, University of Sydney

HomeBuilder grants of A$25,000 are being offered to build or renovate a home as part of the Australian government’s emergency economic response to the coronavirus pandemic. Critics note that the program, framed as stimulus for residential construction, benefits already well-off households. It ignores the realities of the housing market, especially the affordability crisis, with housing stress affecting precarious renters, the homeless and those struggling with bloated mortgage payments.

Homebuilder appears to be a bewildering policy. It’s likely to support construction work that would have occurred anyway while failing to meet real housing needs.

However, to criticise HomeBuilder simply as bad policy made on the run is to miss a broader picture. HomeBuilder begins to make a lot more sense when understood as a response to the role of housing assets in shaping both economic inequality and electoral politics.

Read more: Scott Morrison’s HomeBuilder scheme is classic retail politics but lousy economics

The rise of the ‘asset economy’

We describe this dynamic as the “asset economy”: our socio-economic positions are defined less and less by employment income and more and more by our holdings of wealth-generating assets, especially housing.

The government has touted HomeBuilder as boosting construction jobs through a “tradie-led” recovery. House-price inflation has made the economy particularly dependent on construction jobs. Construction is the third-biggest employer in Australia and the only industry outside the services sector to have had significant job growth in recent years.

However, the government could have boosted construction jobs at least as much, if not more, by investing in social housing or energy-efficient housing. Why then did it choose to make the already well-off even better off by paying owners to add value to their homes?

Read more: Why the focus of stimulus plans has to be construction that puts social housing first

A long history of looking after home owners

It’s no coincidence that, beyond the initial emergency responses to support household and business incomes, the first substantive stimulus the Coalition government announced went to residential property owners.

The rise of the asset economy has occurred in parallel with a shift in voting patterns. The 2019 Australian Election Study observed a move “away from occupation-based voting and towards asset-based voting”. Voters who own housing – owner-occupiers and investors – strongly favour the Liberal and National parties.

Our research on the asset economy reveals the long-term drivers of Australia’s asset-based politics. HomeBuilder is the latest in a long line of Australian government policies over the past four decades to encourage, prop up and reward residential property ownership. These policies have included selling off public housing, tax incentives (especially negative gearing and capital gains tax exemption for the family home) and promoting home ownership as an alternative to welfare programs such as public pensions.

Read more: Fall in ageing Australians' home-ownership rates looms as seismic shock for housing policy

These policies have not simply encouraged home ownership – they have transformed it. Nowadays the home is a financial asset, an investment financed by growing debt that is supposed to generate capital gains.

Property price increases, driven by the liberalisation of credit and low interest rates, came to be seen as a key route to economic security for households in an economy with stagnant wages and precarious employment. Credit-driven home ownership expanded and property prices grew. Many property-owning households saw major gains in their wealth portfolios.

A renovation costing A$150,000 – the minimum needed to get a HomeBuilder grant – will greatly increase the home’s value, including a $25,000 boost from the government.

Dan Peled/AAP

A renovation costing A$150,000 – the minimum needed to get a HomeBuilder grant – will greatly increase the home’s value, including a $25,000 boost from the government.

Dan Peled/AAP

Read more: HomeBuilder might be the most-complex least-equitable construction jobs program ever devised

Housing is now a driver of inequality

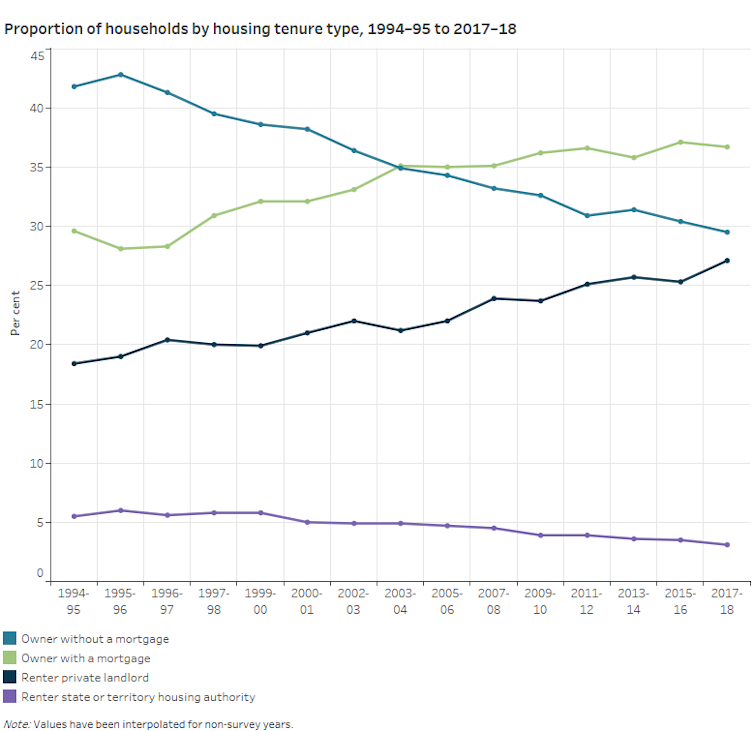

Credit-driven home purchases pushed prices to heights where it became increasingly difficult for people to enter the market. In Australia as well as in other Anglo-capitalist countries ― including the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada ― rates of home ownership show the same pattern from 1980 to 2020: increases followed by decreases.

In large cities such as Sydney and Melbourne price inflation over time has made it virtually impossible to buy a house on the basis of an average wage alone. As a result, private rental markets have expanded, rents have soared and new modes of occupancy have emerged, including multigenerational and shared living. These renters are not simply locked out of home ownership but also out of the wealth it generates.

Source: AIHW. Data: ABS 2019, CC BY

These trends have opened up a rift between those with and without housing assets. This entails not just major differences in levels and patterns of wealth accumulation, but also in life chances. The asset economy has fundamentally reworked the social structure, or what sociologists study as patterns of “class” or “stratification”.

This means even when people have similar jobs or earn the same wages, deep inequalities can exist between those who own assets and those who do not.

These trends are particularly notable among younger generations, giving rise to stark new forms of inequality. Those who are set to inherit housing assets or whose access to parental wealth offers a route into home ownership have a distinct advantage. They can benefit from property-based asset inflation and capital gains.

Read more:

The housing boom propelled inequality, but a coronavirus housing bust will skyrocket it

Shoring up the base in a crisis

HomeBuilder is a product of the electoral politics that emerged out of this asset economy. Asset owners vote with their feet and resist any changes that would jeopardise the long-lived advantages that asset ownership gives them. The result of the 2019 federal election, when Labor’s policy was to reduce the benefits available from negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount, showed this.

The government knows as long as it keeps in place the advantages that flow to home owners, residential property investors and the “bank of mum and dad”, they form a powerful core of the Coalition’s electoral base. It’s offering a stimulus measure directed specifically at this constituency, adding yet more value to their assets at a time of economic uncertainty. HomeBuilder is an asset owner’s policy aimed at appeasing and shoring up the Liberal-National party’s electoral base.

As home ownership rates decline and asset-based inequalities increase, just how long such tactics can produce electoral success remains a critical question.

Source: AIHW. Data: ABS 2019, CC BY

These trends have opened up a rift between those with and without housing assets. This entails not just major differences in levels and patterns of wealth accumulation, but also in life chances. The asset economy has fundamentally reworked the social structure, or what sociologists study as patterns of “class” or “stratification”.

This means even when people have similar jobs or earn the same wages, deep inequalities can exist between those who own assets and those who do not.

These trends are particularly notable among younger generations, giving rise to stark new forms of inequality. Those who are set to inherit housing assets or whose access to parental wealth offers a route into home ownership have a distinct advantage. They can benefit from property-based asset inflation and capital gains.

Read more:

The housing boom propelled inequality, but a coronavirus housing bust will skyrocket it

Shoring up the base in a crisis

HomeBuilder is a product of the electoral politics that emerged out of this asset economy. Asset owners vote with their feet and resist any changes that would jeopardise the long-lived advantages that asset ownership gives them. The result of the 2019 federal election, when Labor’s policy was to reduce the benefits available from negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount, showed this.

The government knows as long as it keeps in place the advantages that flow to home owners, residential property investors and the “bank of mum and dad”, they form a powerful core of the Coalition’s electoral base. It’s offering a stimulus measure directed specifically at this constituency, adding yet more value to their assets at a time of economic uncertainty. HomeBuilder is an asset owner’s policy aimed at appeasing and shoring up the Liberal-National party’s electoral base.

As home ownership rates decline and asset-based inequalities increase, just how long such tactics can produce electoral success remains a critical question.

Authors: Lisa Adkins, Professor of Sociology and Head of School of Social and Political Sciences, University of Sydney