We need a new childcare system that encourages women to work, not punishes them for it

- Written by Fiona David, Visiting Fellow, University of Western Australia

In previous recessions in Australia, far larger numbers of men than women lost their jobs. This reflected realities at that time. Men had higher levels of workforce participation than women, and the construction and manufacturing industries were particularly hard hit.

But in 2020, the composition of the workforce has changed. While far from even, today, women’s participation in the economy sits at 61% compared to 71% for men.

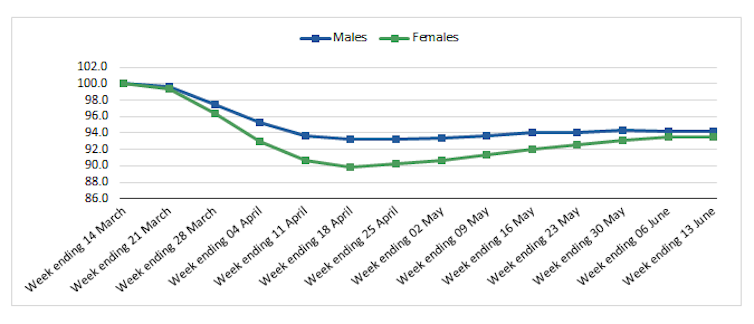

Recent payroll statistics show both men and women are losing their jobs in the pandemic, although women were particularly hard hit in its early stages.

Change in payroll jobs by sex since March 14, 2020.

Australian bureau of statistics

Change in payroll jobs by sex since March 14, 2020.

Australian bureau of statistics

Of course, paid employment is not the only work that gets done. Historically women have carried the bulk of caring work.

Statistics from the government’s gender agency suggest during COVID-19, more women than men are reporting heavier caring responsibilities, both for children and adults, as well as housework.

This context is important to keep in mind when noting the government’s COVID-19 childcare relief package ended on Monday. Under the package, the government’s various childcare subsidy payments were suspended and it provided childcare centres with 50% of the hourly rate cap based on enrolment numbers between February 19 and March 2.

Parents were not required to pay fees. Now, the pre-existing complex system of subsidies has been reinstated and parents will once again be charged fees.

Read more: Morrison has rescued childcare from COVID-19 collapse – but the details are still murky

Added to this, the JobKeeper payment will end from July 20 for employees of childcare providers, which will impact childcare workers as well as cooks, managers, admin staff and cleaners in these centres.

There will be A$708 million in funding for services to replace JobKeeper from July 13 until September 27. This money will be used to pay childcare services 25% of the fee revenue they received before COVID-19 saw parents pulling children out of attendance.

The end of this package is a double hit to women. It hits an industry mostly staffed by women, and removes free child-care when women are struggling with increased caring responsibilities and job losses.

This is deeply concerning from the perspective of gender equity. But if that is not reason enough, the economics of the decision should give pause for thought.

The system pushes women with children away from work

It is two years since accounting firm KPMG developed the “workforce disincentive rate” — a measure of the economic deterrence facing women wanting to return to work after having children, under our existing system of tax and benefits.

This rates the proportion of any extra earnings lost to a family after taking account of additional income tax paid, loss of family payments, loss of childcare payments and increased out-of-pocket childcare costs when women return to work after having children.

A 100% workforce disincentive rate means a family is no better off with the mother working more hours. A rate of more than 100% indicates the family is financially worse off when the mother works additional hours.

The KPMG study found workforce disincentive rates of between 75-120% are common for mothers seeking to increase their work beyond three days a week.

This means that, in many cases, women working additional days or taking additional shifts under the old system are financially worse off.

Under the current system, working part time makes more financial sense for many women.

Shutterstock

Under the current system, working part time makes more financial sense for many women.

Shutterstock

The study found professional, university-educated women are disproportionately affected.

Often, their fourth or fifth working day will cause the family’s income to exceed a threshold, significantly reducing the family’s childcare subsidy entitlement.

This means that while many women return to part-time work after having children, far fewer return to full-time work. And this has flow-on effects throughout the economy and impedes the career progression of women.

This is the economics of the system to which Australian families have just been returned. This is the economics that needs to be urgently reconsidered, given our shared imperitive to find ways to stimulate economic growth.

Economic recovery depends on women

Australia’s economic recovery depends on finding ways to support and unlock economic growth and jobs. One way to do this is to unlock the productivity gains that come from increasing women’s workforce participation.

KPMG estimates even halving the gap between male and female workforce participation would increase our annual GDP by A$60 billion over the next two decades.

One of the barriers to women going to work is the cost of childcare. We see the results in the labour force statistics. Women make up 37.7% of all full-time employees and 68.2% of all part-time employees.

Read more: COVID-19 has laid bare how much we value women's work, and how little we pay for it

Australian families have now had a taste of what it is like to the have access to fee-free childcare. Statistics are not available yet to enable us to understand exactly who took advantage of this system, but one thing is for certain. The economics of fee-free childcare are fundamentally different to the economics of the old system of childcare, which involved a complex interaction between subsidies and tax transfers.

It is possible fee-free childcare saw some women either being able to afford to return to work or increase their working hours.

For too long, Australian working women have literally carried the cost of childcare, and suffered the impact on their own careers.

It is time to recognise that delivering a new system of childcare, that does not disincentivise working women, would not only support our combined efforts to achieve gender equality, it would also constitute a major economic reform with benefits for everyone.

Authors: Fiona David, Visiting Fellow, University of Western Australia