Birdwatching increased tenfold last lockdown. Don't stop, it's a huge help for bushfire recovery

- Written by Ayesha Tulloch, DECRA Research Fellow, University of Sydney

Many Victorians returning to stage three lockdown will be looking for ways to pass the hours at home. And some will be turning to birdwatching.

When Australians first went into lockdown in March, the combination of border closures, lockdowns and the closure of burnt areas from last summer’s bushfires meant those who would have travelled far and wide to watch their favourite birds, instead stayed home.

Yet, Australians are reporting bird sightings at record rates – they’ve just changed where and how they do it.

In fact, Australian citizen scientists submitted ten times the number of backyard bird surveys to BirdLife Australia’s Birdata app in April compared with the same time last year, according to BirdLife Australia’s Dr Holly Parsons.

But it’s not just a joyful hobby. Australia’s growing fascination with birds is vital for conservation after last summer’s devastating bushfires reduced many habitats to ash.

Birds threatened with extinction

Australia’s native plants and animals are on the slow path to recovery after the devastating fires last summer. In our research that’s soon to be published, we found the fires razed forests, grasslands and woodlands considered habitat for 832 species of native vertebrate fauna. Of these, 45% are birds.

Some birds with the largest areas of burnt habitat are threatened with extinction, such as the southern rufous scrub-bird and the Kangaroo Island glossy black-cockatoo.

Government agencies and conservation NGOs are rolling out critical recovery actions.

But citizen scientists play an important role in recovery too, in the form of monitoring. This provides important data to inform biodiversity disaster research and management.

Record rates of birdwatching

Birdwatchers have recorded numerous iconic birds affected by the fires while observing COVID-19 restrictions. They’ve been recorded in urban parks and city edges, as well as in gardens and on farms.

In April 2020, survey numbers in BirdLife Australia’s Birds in Backyards program jumped to 2,242 – a tenfold increase from 241 in April 2019.

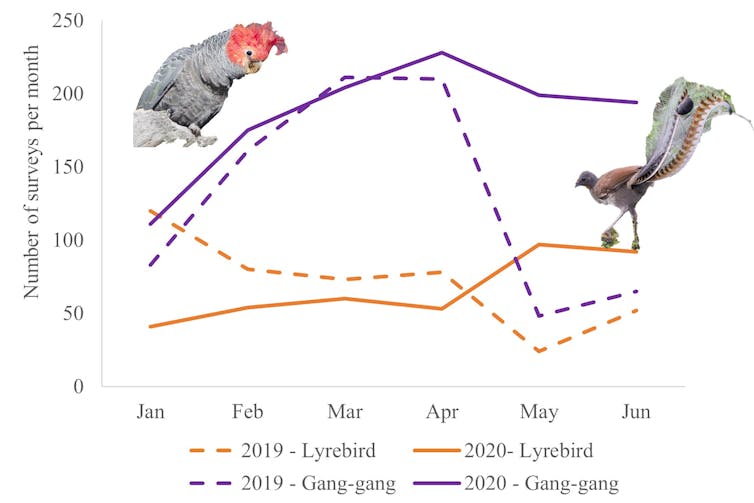

Change in the number of area-based surveys by Australian citizen scientists over the first six months of 2019 compared with 2020. Data sourced from BirdLife Australia’s Birdata database.

Change in the number of area-based surveys by Australian citizen scientists over the first six months of 2019 compared with 2020. Data sourced from BirdLife Australia’s Birdata database.

Similarly, reporting of iconic birds impacted by the recent bushfires has increased.

Between January and June, photos and records of gang-gang cockatoos in the global amateur citizen science app iNaturalist increased by 60% from 2019 to 2020. And the number of different people submitting these records doubled from 26 in 2019 to 53 in 2020.

Read more: Want to help save wildlife after the fires? You can do it in your own backyard

What’s more, reporting of gang-gangs almost doubled in birding-focused apps, such as Birdlife Australia’s Birdata, which recently added a bushfire assessment tool .

The huge rise in birdwatching at home has even given rise to new hashtags you can follow, such as #BirdingatHome on Twitter, and #CuppaWithTheBirds on Instagram.

A gang-gang effort: why we’re desperate for citizen scientists

The increased reporting rates of fire-affected birds is good news, as it means many birds are surviving despite losing their home. But they’re not out of the woods yet.

Their presence in marginal habitats within and at the edge of urban and severely burnt areas puts them more at risk. This includes threats from domestic cat and dog predation, starvation due to inadequate food supply, and stress-induced nest failure.

That’s why consolidating positive behaviour change, such as the rise in public engagement with birdwatching and reporting, is so important.

A female superb lyrebird calling to her reflection in a parked car in suburbia. Her nest was later discovered 100 meters from the carpark.Citizen science programs help increase environmental awareness and concern. They also improve the data used to inform conservation management decisions, and inform biodiversity disaster management.

For example, improved knowledge about where birds go after fire destroys their preferred habitat will help conservation groups and state governments prioritise locations for recovery efforts. Such efforts include control of invasive predators, supplementary feeding and installation of nest boxes.

Gang gang Cockatoo hanging out on a street sign in Canberra.

Athena Georgiou/Birdlife Photography

Gang gang Cockatoo hanging out on a street sign in Canberra.

Athena Georgiou/Birdlife Photography

Better understanding of how bushfire-affected birds use urban and peri-urban habitats will help governments with long-term planning that identifies and protects critical refuges from being cleared or degraded.

And new data on where birds retreat to after fires is invaluable for helping us understand and plan for future bushfire emergencies.

So what can you do to help?

If you have submitted a bird sighting or survey during lockdown, keep at it! If you have never done a bird survey before, but you see one of the priority birds earmarked for special recovery efforts, please report them.

Read more: Six million hectares of threatened species habitat up in smoke

There are several tools available to the public for reporting and learning about birds.

iNaturalist asks you to share a photo or video or sound recording, and a community of experts identifies it for you.

BirdLife’s Birds in Backyards program includes a “Bird Finder” tool to help novice birders identify that bird sitting on the back verandah. Once you’ve figured out what you’re seeing, you can log your bird sightings to help out research and management.

The majority of habitat for Kangaroo Island glossy black cockatoos burnt last summer.

Bowerbirdaus/Wikimedia, CC BY-SA

The majority of habitat for Kangaroo Island glossy black cockatoos burnt last summer.

Bowerbirdaus/Wikimedia, CC BY-SA

For more advanced birders who can identify birds without guidance, options include eBird and BirdLife’s Birdata app. This will help direct conservation groups to places where help is most needed.

Finally, if there are fire-affected birds, such as lyrebirds and gang-gang cockatoos, in your area, it’s especially important to keep domestic dogs and cats indoors, and encourage neighbours to do the same. Report fox sightings to your local council.

Read more: Lots of people want to help nature after the bushfires – we must seize the moment

If you come across a bird that’s injured or in distress, it’s best to contact a wildlife rescue organisation, such as Wildcare Australia (south-east Queensland), WIRES (NSW) or Wildlife Victoria.

By ensuring their homes are safe and by building a better bank of knowledge about where they seek refuge in times of need, we can all help Australia’s unique wildlife.

Authors: Ayesha Tulloch, DECRA Research Fellow, University of Sydney