The law is a man's world. Unless the culture changes, women will continue to be talked over, marginalised and harassed

- Written by Kate Galloway, Associate Professor of Law, Griffith University

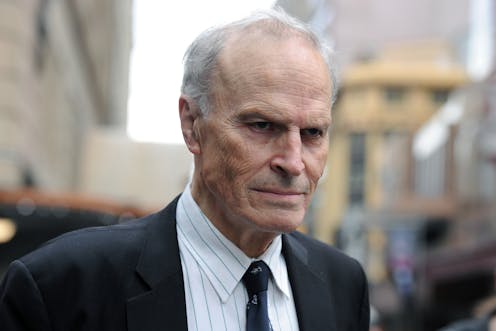

For many, the allegations of sexual harassment against Dyson Heydon came as a shock. It seems difficult to imagine a senior member of the legal profession, a justice of the High Court, would engage in inappropriate or potentially unlawful behaviour.

Yet, sexual harassment in the legal profession is longstanding, and has proven an intractable problem in its incidence, reporting and effects. Nearly half of all female lawyers in Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific report being sexually harassed at work.

Read more: High Court apologises for Dyson Heydon's sexual harassment of six associates

This is at least partly to do with the culture of the profession. This culture has been built by men for men over centuries, and the legal profession continues to rely heavily on personal networks that by their very nature reinforce the status quo.

Tackling endemic sexual harassment requires a shift in the norms that make it an “open secret” – known about but ignored – and accepting women as professional equals rather than sexual objects.

A man’s world

The legal profession is traditionally the preserve of men. Women were for a long time under a “legal disability”, prevented from studying law and from practice. The first women practitioners were admitted in Australia in 1915 (Queensland) and 1917 (South Australia), and it was many more years before women began serving as judges.

Progress has been made in recent years in women studying law. From the mid-1980s, law schools were enrolling approximately equal numbers of men and women. Now, women comprise approximately 60% of law graduates.

Yet, women remain underrepresented in the senior ranks of the profession. In the mid-1990s, the Australian Law Reform Commission found women continued to be underrepresented in positions of influence and were concentrated in the less prestigious and well-paid areas of the profession.

This continues to be true today. In New South Wales, for example, women comprise approximately 25% of partners in law firms and 11% of senior counsel. As for the bar generally, only 23% of barristers in NSW are women.

Of particular concern is that lack of diversity at the bar means lack of diversity in the pool from which judges are appointed. The proportion of women judges and magistrates is highest in the ACT (54%) and Victoria (42%), but in most other jurisdictions, women make up only around a third of judicial officers.

Unless the government of the day is committed to increase diversity on the bench, the composition of the judiciary will not change in a way that reflects society’s needs.

The culture tacitly accepts sexual harassment

For all of the time women have been absent from the profession broadly, and in its senior positions particularly, the law has been populated by men who, consciously and unconsciously, have influenced its culture based on their own preferences and biases.

Consequently, the legal profession frequently displays masculine norms, to the detriment of women.

A recent study found, for instance, that female High Court judges were interrupted by counsel more frequently than their male colleagues. These findings reflect broader social norms about men interrupting women’s speech as a typical way of asserting male dominance.

Read more: To achieve gender equality, we must first tackle our unconscious biases

In a hierarchical profession like law, which is highly competitive and performance-oriented, sexual harassment is another feature of male dominance. The culture of the legal profession, which has excluded women for centuries, continues to tacitly accept this behaviour.

This is why, when allegations about sexual harassment are made public, we often hear the behaviour was an “open secret”.

There are two consequences of this culture that help explain why sexual harassment is so persistent. First, those who are harassed are themselves expected to adhere to the norm, and accept the behaviour or leave. Secondly, witnesses will not themselves see fit to speak out against it.

Such unethical, now unlawful, behaviour will only continue within this closed system, unless a broader cultural change is made.

Networks are key to professional advancement

Reinforcing the predominance of men in the senior ranks of the profession is the importance of personal networks to advancement.

Mentoring relationships are integral to the development of junior lawyers. Universities recognise this, and promote student placements in professional internships as a way of developing these networks.

Here, too, women have long found it more difficult to develop the types of networks needed to succeed. Advancement frequently requires not only a mentor, but a sponsor – someone “on the inside” – who will open doors to professional opportunities.

The majority of those “on the inside” are men, and their conscious and unconscious bias can exclude women from opportunities to advance their careers.

Read more: Australia urgently needs an independent body to hold powerful judges to account

Junior lawyers, especially those without established professional networks, must also compete to establish relationships with senior practitioners - including with judges through sought-after associateships.

The power in these relationships rests with the senior practitioner, most of whom are men in charge of their own domain and well-connected in the upper echelons of the legal fraternity.

Women are qualified to fill these coveted positions, but once there, the question becomes whether they are equipped to tolerate the “open secret” of sexual harassment as the price of maintaining the relationships they need for advancement.

In this kind of environment, a junior lawyer has very little power to call out unwanted sexual advances - particularly when the behaviour is accepted by those around her.

This contributes to the attrition of talented women from the profession and, of course, entrenches the male domination of its senior ranks.

Cause for optimism

Despite this grim picture, something changed this week. Allegations made by the most junior against the most senior were listened to and acted on.

While seemingly a small step, it represents a huge challenge to the culture of the “open secret” of sexual misconduct in the legal profession and the possibility of establishing new cultural benchmarks for the law.

Authors: Kate Galloway, Associate Professor of Law, Griffith University