Seeing is believing: how media mythbusting can actually make false beliefs stronger

- Written by Eryn Newman, Lecturer, Australian National University

As the COVID-19 pandemic has swept the world, politicians, medical experts and epidemiologists have taught us about flattening curves, contact tracing, R0 and growth factors. At the same time, we are facing an “infodemic” – an overload of information, in which fact is hard to separate from fiction.

Misinformation about coronavirus can have serious consequences. Widespread myths about “immune boosters”, supposed “cures”, and conspiracy theories linked to 5G radiation have already caused immediate harm. In the long term they make may people more complacent if they have false beliefs about what will protect them from coronavirus.

Social media companies are working to reduce the spread of myths. In contrast, mainstream media and other information channels have in many cases ramped up efforts to address misinformation.

But these efforts may backfire by unintentionally increasing public exposure to false claims.

Read more: We're in danger of drowning in a coronavirus 'infodemic'. Here's how we can cut through the noise

The ‘myth vs fact’ formula

News media outlets and health and well-being websites have published countless articles on the “myths vs facts” about coronavirus. Typically, articles share a myth in bold font and then address it with a detailed explanation of why it is false.

This communication strategy has been used previously in attempts to combat other health myths such as the ongoing anti-vaccine movement.

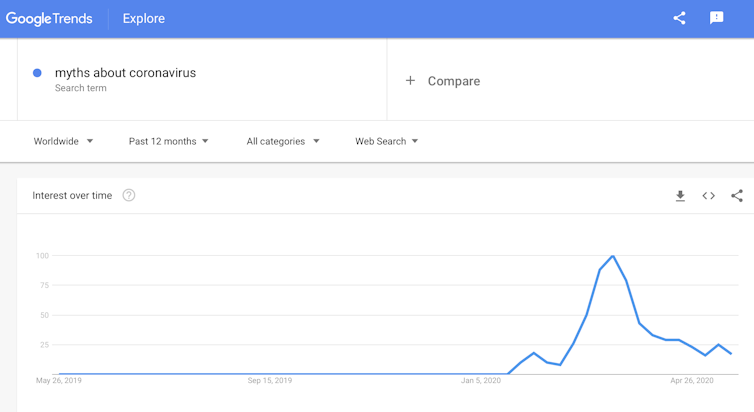

One reason for the prevalence of these articles is that readers actively seek them out. The Google search term “myths about coronavirus”, for example, saw a prominent global spike in March.

According to Google Trends, searches for ‘myths about coronavirus’ spiked in March.

Google Trends

According to Google Trends, searches for ‘myths about coronavirus’ spiked in March.

Google Trends

Debunking false information, or contrasting myths with facts, intuitively feels like it should effectively correct myths. But research shows that such correction strategies may actually backfire, by making misinformation seem more familiar and spreading it to new audiences.

Familiarity breeds belief

Cognitive science research shows people are biased to believe a claim if they have seen it before. Even seeing it once or twice may be enough to make the claim more credible.

This bias happens even when people originally think a claim is false, when the claim is not aligned with their own beliefs, and when it seems relatively implausible. What’s more, research shows thinking deeply or being smart does not make you immune to this cognitive bias.

The bias comes from the fact humans are very sensitive to familiarity but we are not very good at tracking where the familiarity comes from, especially over time.

One series of studies illustrates the point. People were shown a series of health and well-being claims one might typically encounter on social media or health blogs. The claims were explicitly tagged as true or false, just like in a “myth vs fact” article.

When participants were asked which claims were true and which were false immediately after seeing them, they usually got it right. But when they were were tested a few days later, they relied more on feelings of familiarity and tended to accept previously seen false claims as true.

The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Older adults were especially susceptible to this repetition. The more often they were initially told a claim was false, the more they believed it to be true a few days later.

For example, they may have learned that the claim “shark cartilage is good for your arthritis” is false. But by the time they saw it again a few days later, they had forgotten the details.

All that was left was the feeling they had heard something about shark cartilage and arthritis before, so there might be something to it. The warnings turned false claims into “facts”.

The lesson here is that bringing myths or misinformation into focus can make them more familiar and seem more valid. And worse: “myth vs fact” may end up spreading myths by showing them to new audiences.

Read more:

Why is it so hard to stop COVID-19 misinformation spreading on social media?

What I tell you three times is true

Repeating a myth may also lead people to overestimate how widely it is accepted in the broader community. The more often we hear a myth, the more we will think it is widely believed. And again, we are bad at remembering where we heard it and under what circumstances.

For instance, hearing one person say the same thing three times is almost as effective in suggesting wide acceptance as hearing three different people each say it once.

The concern here is that repeated attempts at correcting a myth in media outlets might mistakenly lead people to believe it is widely accepted in the community.

Memorable myths

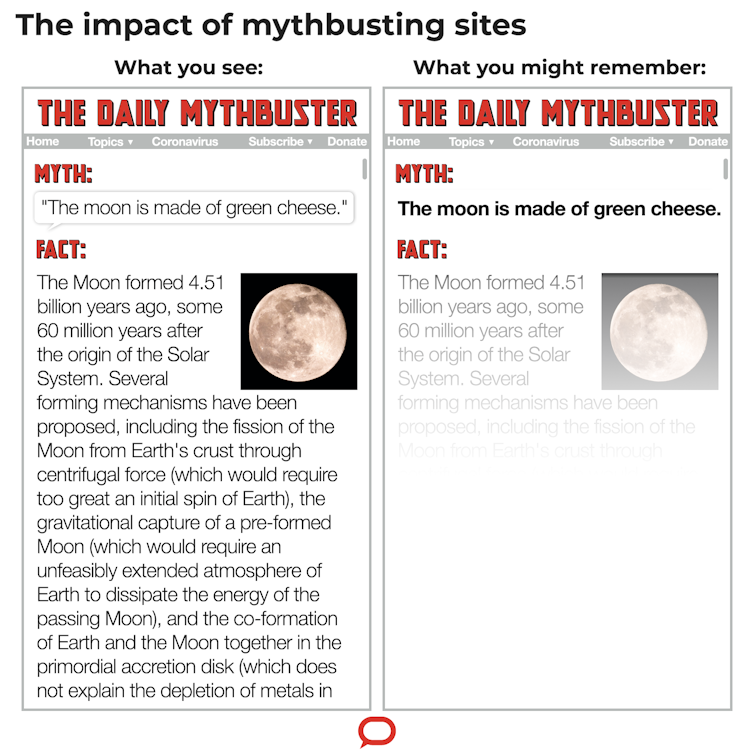

Myths can be sticky because they are often concrete, anecdotal and easy to imagine. This is a cognitive recipe for belief. The details required to unwind a myth are often complicated and difficult to remember. Moreover, people may not scroll all the way through the explanation of why a myth is incorrect.

Take for example this piece on coronavirus myths. Although we’d rather not expose you to the myths at all, what we want you to notice is that the fine details needed to debunk a myth are generally more complicated than the myth itself.

Complicated stories are hard to remember. The outcome of such articles may be a sticky myth and a slippery truth.

Making the truth stick

If debunking myths makes them more believable, how do we promote the truth?

When information is vivid and easy to understand, we are more likely to recall it. For instance, we know placing a photograph next to a claim increases the chances people will remember (and believe) the claim.

Making the truth concrete and accessible may help accurate claims dominate the public discourse (and our memories).

Other cognitive tools include using concrete language, repetition, and opportunities to connect information to personal experience, which all work to facilitate memory. Pairing those tools with a focus on truth can help to promote facts at a critical time in human history.

The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Older adults were especially susceptible to this repetition. The more often they were initially told a claim was false, the more they believed it to be true a few days later.

For example, they may have learned that the claim “shark cartilage is good for your arthritis” is false. But by the time they saw it again a few days later, they had forgotten the details.

All that was left was the feeling they had heard something about shark cartilage and arthritis before, so there might be something to it. The warnings turned false claims into “facts”.

The lesson here is that bringing myths or misinformation into focus can make them more familiar and seem more valid. And worse: “myth vs fact” may end up spreading myths by showing them to new audiences.

Read more:

Why is it so hard to stop COVID-19 misinformation spreading on social media?

What I tell you three times is true

Repeating a myth may also lead people to overestimate how widely it is accepted in the broader community. The more often we hear a myth, the more we will think it is widely believed. And again, we are bad at remembering where we heard it and under what circumstances.

For instance, hearing one person say the same thing three times is almost as effective in suggesting wide acceptance as hearing three different people each say it once.

The concern here is that repeated attempts at correcting a myth in media outlets might mistakenly lead people to believe it is widely accepted in the community.

Memorable myths

Myths can be sticky because they are often concrete, anecdotal and easy to imagine. This is a cognitive recipe for belief. The details required to unwind a myth are often complicated and difficult to remember. Moreover, people may not scroll all the way through the explanation of why a myth is incorrect.

Take for example this piece on coronavirus myths. Although we’d rather not expose you to the myths at all, what we want you to notice is that the fine details needed to debunk a myth are generally more complicated than the myth itself.

Complicated stories are hard to remember. The outcome of such articles may be a sticky myth and a slippery truth.

Making the truth stick

If debunking myths makes them more believable, how do we promote the truth?

When information is vivid and easy to understand, we are more likely to recall it. For instance, we know placing a photograph next to a claim increases the chances people will remember (and believe) the claim.

Making the truth concrete and accessible may help accurate claims dominate the public discourse (and our memories).

Other cognitive tools include using concrete language, repetition, and opportunities to connect information to personal experience, which all work to facilitate memory. Pairing those tools with a focus on truth can help to promote facts at a critical time in human history.

Authors: Eryn Newman, Lecturer, Australian National University