What dreams may come: why you're having more vivid dreams during the pandemic

- Written by Dr Rosie Gibson, Research Officer, Sleep/Wake Research Centre, College of Health, Massey University

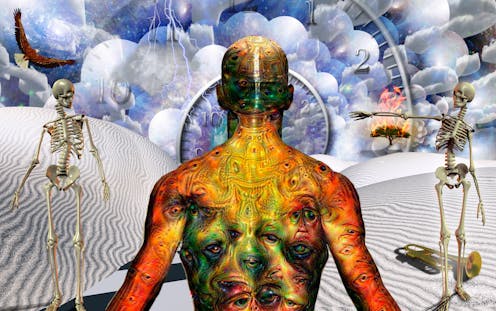

An interesting side effect of the coronavirus pandemic is the number of people who say they are having vivid dreams.

Many are turning to blogs and social media to describe their experiences.

While such dreams can be confusing or distressing, dreaming is normal and considered helpful in processing our waking situation, which for many people is far from normal at the moment.

While we are sleeping

Adults are recommended to sleep for seven to nine hours to maintain optimal health and well-being.

Read more: No wonder isolation's so tiring. All those extra, tiny decisions are taxing our brains

When we sleep we go through different stages which cycle throughout the night. This includes light and deep sleep and a period known as rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, which features more prominently in the second half of the night. As the name implies, during REM sleep the eyes move rapidly.

Dreams can occur within all sleep stages but REM sleep is considered responsible for highly emotive and visual dreams.

We typically have several REM dream periods a night, yet we do not necessarily remember the experiences and content. Researchers have identified that REM sleep has unique properties that help us regulate our mood, performance and cognitive functioning.

Some say dreams act like a defence mechanism for our mental health, by giving us a simulated opportunity to work through our fears and to rehearse for stressful real-life events.

This global pandemic and associated restrictions may have impacts on how and when we sleep. This has positive effects for some and negative effects for others. Both situations can lead to heightened recollection of dreams.

Disrupted sleep and dreams

During this pandemic, studies from China and the UK show many people are reporting a heightened state of anxiety and are having shorter or more disturbed sleep.

Ruminating about the pandemic, either directly or via the media, just before going to bed can work against our need to relax and get a good night’s sleep. It may also provide fodder for dreams.

When we are sleep deprived, the pressure for REM sleep increases and so at the next sleep opportunity a so-called rebound in REM sleep occurs. During this time dreams are reportedly more vivid and emotional than usual.

More time in bed

Other studies indicate that people may be sleeping more and moving less during the pandemic.

If you’re working and learning from home on flexible schedules without the usual commute it means you avoid the morning rush and don’t need to get up so early. Heightened dream recall has been associated with having a longer sleep as well as waking more naturally from a state of REM sleep.

If you’re at home with other people you have a captive audience and time to exchange dream stories in the morning. The act of sharing dreams reinforces our memory of them. It might also prepare us to remember more on subsequent nights.

This has likely created a spike in dream recall and interest during this time.

The pandemic concerns

Dreaming can help us to cope mentally with our waking situation as well as simply reflect realities and concerns.

In this time of heightened alert and changing social norms, our brains have much more to process during sleep and dreaming. More stressful dream content is to be expected if we feel anxious or stressed in relation to the pandemic, or our working or family situations.

Hence more reports of dreams containing fear, embarrassment, social taboos, occupational stress, grief and loss, unreachable family, as well as more literal dreams around contamination or disease are being recorded.

An increase in unusual or vivid dreams and nightmares is not surprising. Such experiences have been reported before at times associated with sudden change, anxiety or trauma, such as the aftermath of the terrorist attacks in the US in 2001, or natural disasters or war.

Those with an anxiety disorder or experiencing the trauma first-hand are highly likely also to experience changes to dreams.

But such changes are also reported by those witnessing events like the 9/11 attacks second-hand or via the media.

Problems solved in dreams

One theory on dreams is they serve to process the emotional demands of the day, to commit experiences to memory, solve problems, adapt and learn.

This is achieved through the reactivation of particular brain areas during REM sleep and the consolidation of neural connections.

During REM the areas of the brain responsible for emotions, memory, behaviour and vision are reactivated (as opposed to those required for logical thinking, reasoning and movement, which remain in a state of rest).

The activity and connections made during dreaming are considered to be guided by the dreamer’s waking activities, exposures and stressors.

The neural activity has been proposed to synthesise learning and memory. The actual dream experience is more a by-product of this activity, which we assemble into a more logical narrative when the remainder of the brain attempts to catch up and reason with the activity on waking.

Please … go to sleep

If disrupted sleep and dreams are problematic or distressing for you, consider how your sleep schedule and behaviour has changed with the pandemic. Maybe seek advice for supporting your sleep and well-being during this time.

My colleagues and I at the Sleep/Wake Research Centre have produced several information sheets on sleep during the pandemic.

We are also conducting a survey concerning the sleep of people living in New Zealand. This explores factors affecting sleep during the pandemic, and participants can comment on their dreaming.

Authors: Dr Rosie Gibson, Research Officer, Sleep/Wake Research Centre, College of Health, Massey University