Buried under colonial concrete, Botany Bay has even been robbed of its botany

- Written by Rebecca Hamilton, Postdoctoral Researcher in Palaeoecology, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History

The HMS Endeavour’s week-long stay on the shores of Kamay in 1770 yielded so many botanical specimens unknown to western science, Captain James Cook called the area Botany Bay.

During this visit, the ship’s natural history expert Joseph Banks spoke favourably of the landscape, saying it resembled the “moorlands of England” with “knee-high brushes of plants stretching over gentle and treeless hills as far as the eye could see”.

Since then, Kamay has become an icon of Australia’s convict history and emblematic of the dispossession of Indigenous people from country.

However, memories of the pre-British flora have largely been lost. Ongoing research drawing on ecological data, and Indigenous and European histories, reveals what this environment once looked like. It shows many of the assumptions about the historical landscape we hold today may actually be wrong.

The site better reflects 20th-century European exploitation of the landscape than it does early or pre-British Botany Bay.

From swamps to suburbs

Today, the northern shore of Kamay acts as Australia’s gateway to the world. It hosts Australia’s busiest international airport and one of Australia’s largest container ports, major arterial roads and a rapidly growing residential population.

From the early 19th century, urban development gradually overprinted a vast network of groundwater-fed swamplands, whose catchment extended north from Kamay to what is now the southern boundary of Sydney’s CBD.

These swamps have largely disappeared under the suburbs, or have been corralled into golf course ponds or narrow wetlands alongside Southern Cross Drive - a sight familiar to anyone who has driven between Sydney city and its airport.

Kamay holds a rapidly growing residential population.

Shutterstock

Kamay holds a rapidly growing residential population.

Shutterstock

Viewed by British colonial authorities as both an unhealthy nuisance and a critical resource, the ever-shrinking wetlands played a crucial role in the water supply and industrial development of early Sydney, before becoming polluted and a disease-causing miasma.

A misremembered past

“Natural” remnants of the former swamplands are today considered to have high conservation value under both state and federal environmental and heritage protection legislation.

Read more: Friday essay: histories written in the land - a journey through Adnyamathanha Yarta

But attempting to protect ecosystems that reflect a version of the past has a major constraint. Long-term information about their past species composition and structure can be fragmented, misremembered, or absent.

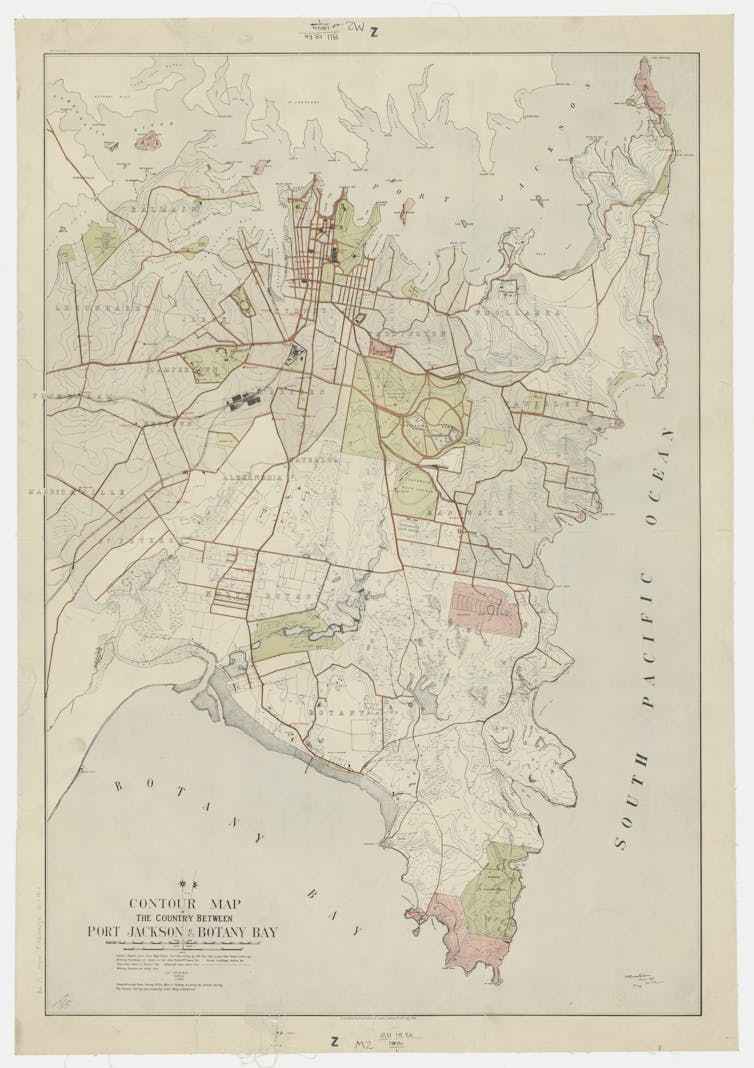

A map showing the Kamay (Botany Bay) Swamplands from 1894.

Image from the Mitchell Collection, State Library of NSW, Author provided

A map showing the Kamay (Botany Bay) Swamplands from 1894.

Image from the Mitchell Collection, State Library of NSW, Author provided

This is especially problematic in the case of the Kamay swamplands, which, like many urban ecosystems, have been fragmented, hydrologically altered, and polluted.

Yet not all is lost. We studied pollen released from flowering plants and conifers, which can accumulate and preserve in sediment layers through time.

Looking at this preserved pollen lets us develop a timeline of vegetation change over hundreds to thousands of years.

Lachlan swamp

One wetland remnant, called Lachlan Swamp, occurs at the springhead of the swamplands in Centennial Parklands. Boardwalks and signs at the site encourage visitors to imagine the swamps and the paperbark forest (Melaleuca quinquenervia) surrounding them as a relic of pre-British Sydney.

Paperbark trees dominate the landscape at Lachlan Swamp.

Author provided

Paperbark trees dominate the landscape at Lachlan Swamp.

Author provided

We used the pollen technique at Lachlan Swamp to determine whether the contemporary ecosystem reflects the pre-European landscape being protected.

And our results reveal that, at the time of British occupation, the swampland was surrounded by an open, Ericaceae-dominated heath. Casuarina and Leptospermum species were the dominant swamp trees, not the swamp paperbark.

This plant community was present at the site for at least the previous 2,000 years, and was only replaced by the contemporary paperbark forest between the 1890s and 1970s.

An 1844 drawing of Lachlan Swamp showing an open landscape.

Image from the Dixon Collection, State Library of NSW, Author provided

An 1844 drawing of Lachlan Swamp showing an open landscape.

Image from the Dixon Collection, State Library of NSW, Author provided

Cultural knowledge

Ongoing work from the La Perouse Aboriginal Community led research team drawing on Indigenous knowledge and European history suggests this open heathland vegetation grew consistently across the Lachlan and Botany Swamps during and prior to European colonisation of Sydney.

Continuous cultural knowledge about the environment, held by local Dharawal people, can provide a rich picture of Kamay’s botany and how it was used – well before the arrival of the HMS Endeavour.

Read more: The Memory Code: how oral cultures memorise so much information

For instance, the Garrara or grass tree (Xanthorrhoea), which is depicted in many early colonial paintings, is a multi-use plant used to construct fishing spears – a tradition upheld today within the La Perouse Aboriginal community.

Similarly, other food and medicinal plants have been long been used by this community. This includes Five Corners (Ericaceae), Native Sarsaparilla (Smilax), Lomandra (Lomandra) and multi-use heath and swamp plants such as the coastal wattle (Acacia longifolia), swamp oak (Casuarina glauca) and coastal tea tree (Leptospermum laevigatum).

Xanthorrhoea plants grew throughout Botany Bay before European colonisation.

Shutterstock

Xanthorrhoea plants grew throughout Botany Bay before European colonisation.

Shutterstock

The plant species described and utilised by the local people correlates with the pre-European vegetation reconstructed from the Lachlan Swamp pollen record, and with what is described in early British records.

Not all is lost

Our common understanding of the Kamay landscape, as recognised in the protected swamp remnant in Centennial Park, is based on a misremembering of the past.

If our future goals are to conserve beautiful, unique ecosystems that have escaped European exploitation and mismanagement – such as the version of Botany Bay described by Banks – it’s crucial to start including and listening to long-term environmental histories to compliment our scientific research.

Read more: The Dreamtime, science and narratives of Indigenous Australia

We must protect a resilient, ecosystem-rich landscape informed by accumulated Indigenous knowledge, passed down over many generations.

Though Sydney’s environmental past may be misremembered, it’s not lost entirely. Its legacy is subtly coded into the remnant landscapes of pre-British occupation, and preserved in the continuous knowledge systems of the land’s first peoples.

With care, it can be read and used to support resilient and authentic urban ecosystems.

Authors: Rebecca Hamilton, Postdoctoral Researcher in Palaeoecology, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History