'Home away from home': reflecting on past airline collapses in Australia

- Written by Tracy Ireland, Professor of Cultural Heritage, University of Canberra

The coronavirus crisis has challenged the global aviation industry in previously unimaginable ways. The latest announcement is Virgin Australia has entered voluntary administration.

While Virgin’s future hangs in the balance, over the one hundred years of civil aviation in Australia there has been a long list of airline casualties. Regardless of what the future holds for Virgin and its staff, the future of the company (and air travel) is certain to be irreparably changed by the pandemic.

Read more: Voluntary administration isn't a death sentence for Virgin Australia – or for competition

Airline crew tend to consider their occupation as not just a job but a way of life. As teary cabin supervisor Tony Smith told the media:

Virgin is my home away from home. They are my brother, my sister, my mum and dad, my grandfather and my grandmother. They’re people I can turn to, to help me get through things, and it’s not just me, it’s a lot of other crew as well … It’s a sense of worth, it’s what keeps a lot of us sane, it keeps our mental health in check.

This strong allegiance to the company is due in part to the emotional labour required to be a flight attendant – the hard work of endlessly smiling and always being polite – and the personal sacrifices of the job. Flight crew routinely miss birthday parties, weddings, funerals and school concerts because of their service to an industry that works around the clock.

Pilots and cabin crew give up a lot to be in the industry – something of themselves and the lives that they might have otherwise lived. This means when airlines collapse they lose more than just a place to go to work: they lose a key part of their identity.

The luxury and the labour of air travel

There is a long history of loyal workers being badly affected by corporate collapses and changes in government aviation policies in Australia, but long-defunct regional airlines have dedicated custodians in regional museums and collections all around Australia.

The Queensland Air Museum maintains relics from an Australian-registered Douglas DC-6 airliner Resolution, which crashed outside San Francisco in 1953. Its loss was the final straw for the financially precarious British Commonwealth Pacific Airlines.

An advertisement for British Commonwealth Pacific Airlines in Australian Women’s Weekly, 1952.

Trove

An advertisement for British Commonwealth Pacific Airlines in Australian Women’s Weekly, 1952.

Trove

In Cooma, the Aviation Pioneers Memorial marks the loss of the Avro Ten airliner Southern Cloud in 1931, which spelled the end of the short-lived Australian National Airways established by Charles Kingsford Smith in 1929.

The shock of the 2001 collapse of Ansett Airlines was as profound and unsettling as the concurrent September 11 terrorist attacks. Two days earlier, the airline had gone into voluntary administration. On the 14th, the airline was grounded. Thousands of passengers and crew were left stranded.

Over the next few months there were attempts to keep a few flight services operational, but the company closed completely on March 4 2002, leaving 16,000 without jobs.

Established in 1935, by the 1960s Ansett was a mainstay of domestic air travel under the government’s “two-airline policy”. At the time of its collapse, Ansett accounted for almost half of the domestic aviation market.

The fallout ran deep: families were separated as pilots sought work overseas, there was a high rate of marriage breakdowns, and a number of crew died by suicide.

As Ansett air hostess Pat Ward said:

There wasn’t great value in being thrown around the sky every day. But the value was in the people that were there and what you could do for them. You were, very often, their lifeline.

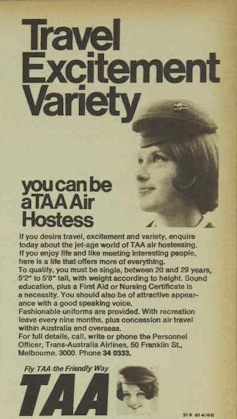

A classified ad for TAA air hostesses published in 1968. Applicants should ‘be of attractive appearance with a good speaking voice’.

Trove

A classified ad for TAA air hostesses published in 1968. Applicants should ‘be of attractive appearance with a good speaking voice’.

Trove

If you visit the Trans-Australia Airlines Museum on any Tuesday morning, you will meet a vibrant group of volunteers who care for the unique collection of memorabilia for the company that flew from 1946 until it merged with Qantas in 1992.

The volunteers include former “hosties” who mingle with technicians and retired pilots. They are eager to share reminiscences about having to “weigh in” when flight attendants’ weight was monitored, or about apprenticeships working alongside fathers and brothers.

John Wren, president of the TAA 25 Year Club, remembers the airline as “a community and source of lifetime employment for my family. In comparison, Qantas was more like the public service!”

More than an industry

Our Heritage of the Air project has been researching Australia’s civil aviation to build a better understanding of what it is about this industry that inspires loyalty.

But aviation is not just an industry: it’s a complex linkage of technology, imagination, design and fashion, with a special kind of emotional attachment.

As airlines have been shut under coronavirus, the flow of people made possible through technologies of flight is being challenged in a way never seen before.

Yet, even as we see aircraft standing idle and airport halls eerily silent, we still rely on airlines and their workers to get everyone home. Air crews are frontline workers and are well aware of the value and necessity of their skills.

As Miranda Diack, vice president of the Flight Attendants’ Association of Australia, told ABC’s The Drum last month:

[The] aviation industry has been always there in every major disaster to rescue people. We’ve been there to bring our citizens home when they have needed help. Maybe it’s time for the government to remember … it might be time to rescue us for a change.

Authors: Tracy Ireland, Professor of Cultural Heritage, University of Canberra