Price-level targeting: how inflation-focused central banks can squeeze more from interest rates

- Written by Mariano Kulish, Professor of Macroeconomics, University of Sydney

The Reserve Bank of Australia has cut its official interest rate to 0.25%. The bank’s governor, Philip Lowe, reckons this is as low as the bank can go.

The cut – the first this century to have been decided outside the normal monthly meeting of the bank’s board – underlines the economic threat posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. It follows the bank cutting the rate by 0.25 points to 0.50% at its February meeting.

Read more: More than a rate cut: behind the Reserve Bank's three point plan

In the time since that meeting, the United States Federal Reserve has also made two emergency cuts, taking the US rate from just below 1.25% to near 0%.

Australia and the US have joined nations across Asia and Europe where rates are near zero and policymakers have run out of wriggle room to cut them further.

US President John F. Kennedy said: “The time to repair the roof is when the sun is shining.”

Conditions are already gloomy, but before the next storm hits it is imperative we think about what we are going to do.

The option most often discussed when rates approach zero is quantitative easing, in which the Reserve Bank (and similar institutions) use newly created money or reserves to buy financial assets such as government and corporate bonds.

Australia’s Reserve Bank has signalled its intention to follow the US Fed and buy government bonds from investors, forcing money into their hands.

Reserve Bank of Australia Governor Philip Lowe outlines plans on Thursday, March 19 2020.

Joel Carrett/AAP

Reserve Bank of Australia Governor Philip Lowe outlines plans on Thursday, March 19 2020.

Joel Carrett/AAP

Read more: 'Yield curve control': the Reserve Bank's plan for when cash rate cuts no longer work

But here I want to explore an alternative policy that should make monetary policy powerful even when interest rates are zero, by changing expectations of where future rates will be.

To achieve it, central banks need to make a subtle but significant change to the target that drives monetary policy.

Inflation versus price

In Australia and many other countries, central banks aim for a target inflation rate – in our case 2% to 3%.

They have less ability to achieve the inflation target when cash rates are close to zero.

Read more: 'Guaranteed to lose money': welcome to the bizarro world of negative interest rates

To fix this, some economists have proposed increasing the inflation target.

The drawback is permanently higher average inflation, which is known to be costly for society.

A better alternative in a world of low interest rates is to replace the inflation target with a price-level target.

The difference is small but significant.

Let’s say the consumer price index begins the year at 100.

An inflation target of 2%-3% would aim at having the consumer price index reach 102-103 by the end of the year. If at some point during the year inflation was higher or lower than 2%-3% annual growth, the goal would be to get it back to that growth rate.

After than was done, the index might end up somewhere higher or lower than 102-103.

A price-level target differs by aiming to stick to a path for the level of the index, and return it to that level if there is any deviation. So if the price level target was 102-103, the target would return to 102-103.

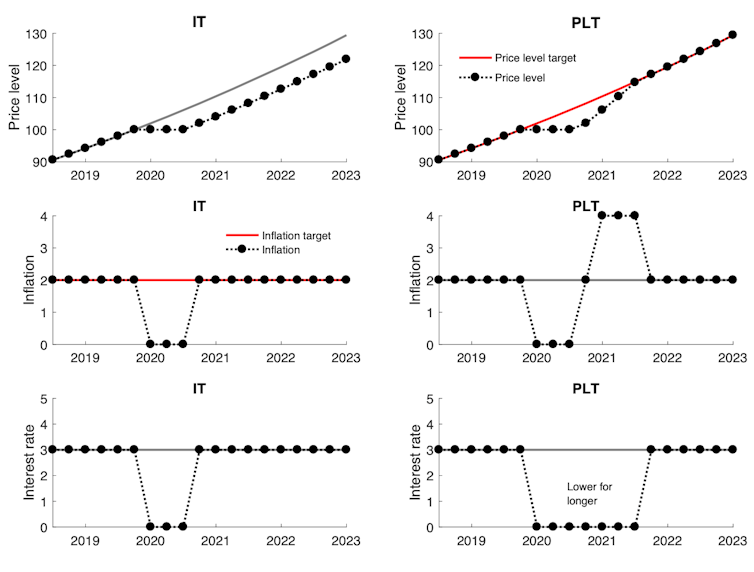

These diagrams compare what would happen under inflation targeting (IT) with what happens now under price-level targeting (PLT).

Mariano Kulish, Author provided

Both begin with a barely distinguishable target: inflation of 2% in the first IT case; and price levels consistent with 2% inflation in the second PLT case.

Where the policy difference becomes evident is after an economic shock that reduces demand for goods and services, and thereby inflation (represented by the dotted line).

The left-hand panels show an inflation-targeting policy response to inflation falling to 0%. The central bank cuts interest rates to get inflation back to 2%. For a period of time inflation is below target.

The right-hand panels show a price-level-targeting policy response. When inflation falls to 0%, the central bank would not be satisfied with just getting it back to 2%, because this will not return the price level to its target path. Instead the bank tries to increase inflation to 4% for a time to compensate. The bank will have to cut interest rates for longer to get back to the price-level target than it would to get back to an inflation target.

The lower for longer strategy

What advantage does this give price-level targeting over inflation targeting?

The answer is that in the present circumstances a price-level target requires low interest rates for longer. Because households and business would know this and expect low interest rates for longer, they are more likely to spend or invest.

Price-level targeting would do more.

A downside, for some, is that when conditions are buoyant it would require the Reserve Bank to keep interest rates higher for longer, which the bank might find politically difficult.

Read more:

The Fed will have to do a lot more than cut rates to zero to stop Wall Street's coronavirus panic

But we’re at the point where all options need to be on the table.

It is uncertain how persistent and negative the consequences of the coronavirus will be. However, the forces keeping interest rates low are likely to persist.

We need to squeeze as much juice from monetary policy as we can.

Mariano Kulish, Author provided

Both begin with a barely distinguishable target: inflation of 2% in the first IT case; and price levels consistent with 2% inflation in the second PLT case.

Where the policy difference becomes evident is after an economic shock that reduces demand for goods and services, and thereby inflation (represented by the dotted line).

The left-hand panels show an inflation-targeting policy response to inflation falling to 0%. The central bank cuts interest rates to get inflation back to 2%. For a period of time inflation is below target.

The right-hand panels show a price-level-targeting policy response. When inflation falls to 0%, the central bank would not be satisfied with just getting it back to 2%, because this will not return the price level to its target path. Instead the bank tries to increase inflation to 4% for a time to compensate. The bank will have to cut interest rates for longer to get back to the price-level target than it would to get back to an inflation target.

The lower for longer strategy

What advantage does this give price-level targeting over inflation targeting?

The answer is that in the present circumstances a price-level target requires low interest rates for longer. Because households and business would know this and expect low interest rates for longer, they are more likely to spend or invest.

Price-level targeting would do more.

A downside, for some, is that when conditions are buoyant it would require the Reserve Bank to keep interest rates higher for longer, which the bank might find politically difficult.

Read more:

The Fed will have to do a lot more than cut rates to zero to stop Wall Street's coronavirus panic

But we’re at the point where all options need to be on the table.

It is uncertain how persistent and negative the consequences of the coronavirus will be. However, the forces keeping interest rates low are likely to persist.

We need to squeeze as much juice from monetary policy as we can.

Authors: Mariano Kulish, Professor of Macroeconomics, University of Sydney