COVID-19 death toll estimated to reach 3,900 by next Friday, according to AI modelling

- Written by Belal Alsinglawi, PhD Candidate in Data Science and ICT Lecturer, Western Sydney University

The coronavirus disease COVID-19 has so far caused about 3,380 deaths, infected about 98,300 people, and is significantly impacting the economy in many countries.

We used predictive analytics, a branch of artificial intelligence (AI), to forecast how many confirmed COVID-19 cases and deaths can be expected in the near future.

Our method predicts that by March 13, the virus death toll will have climbed to 3,913, and confirmed cases will reach 116,250 worldwide, based on data available up to March 5.

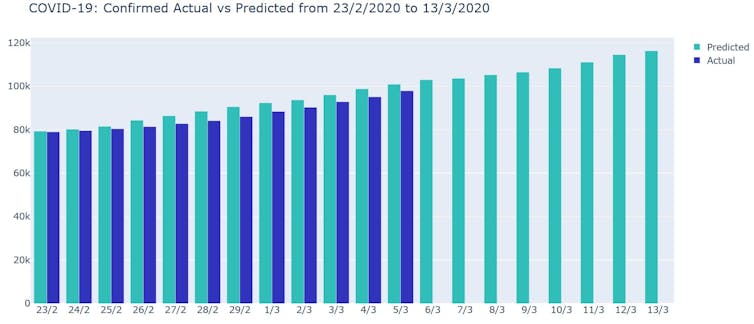

Predicted (green) and confirmed (blue) cases of COVID-19 from February 23 to March 13, as per our simulation. (Note: scale is in tens of thousands.

Author provided (No reuse)

Predicted (green) and confirmed (blue) cases of COVID-19 from February 23 to March 13, as per our simulation. (Note: scale is in tens of thousands.

Author provided (No reuse)

Predicted (purple) and confirmed (red) deaths caused by COVID-19 from February 23 to March 13, as per our simulation. (Note: scale is in thousands, so these numbers are an order of magnitude smaller than those in the graph above.

Author provided (No reuse)

Predicted (purple) and confirmed (red) deaths caused by COVID-19 from February 23 to March 13, as per our simulation. (Note: scale is in thousands, so these numbers are an order of magnitude smaller than those in the graph above.

Author provided (No reuse)

To develop contingency plans and hopefully head off the worst effects of the coronavirus, governments need to be able to anticipate the future course of the outbreak.

This is where predictive analytics could prove invaluable. This method involves finding trends in past data, and using these insights to forecast future events. There’s currently too few Australian cases to generate such a forecast for the country.

Number crunching

As of when this article was published, our model had predicted COVID-19 infections to an accuracy of 96%, and deaths to an accuracy of 99%. To maintain this accuracy, we have to regularly update our data as the global rate of COVID-19’s spread increases or decreases.

Read more: How do we detect if coronavirus is spreading in the community?

Based on data available up to March 5, our model predicts that by March 31 the number of deaths worldwide will surpass 4,500 and confirmed cases will reach 150,000. However, since these projections surpass our short-term window of accuracy, they shouldn’t be considered as reliable as the figures above.

At the moment, our model is best suited for short-term forecasting. To make accurate long-term forecasts, we’ll need more historical data and a better understanding of the variables impacting COVID-19’s spread.

The more historical data we acquire, the more accurate and far-reaching our forecasts can be.

How we made our predictions

To create our simulations, we extracted coronavirus data dating back to January 22, from an online repository provided by the Johns Hopkins University Centre for Systems Science and Engineering.

This time-stamped data detailed the number and locations of confirmed cases of COVID-19, including people who recovered, and those who died.

Choosing an appropriate modelling technique was integral to the reliability of our results. We used time series forecasting, a method that predicts future values based on previously observed values. This type of forecasting has proven suitable to predict future outbreaks of a disease.

We ran our simulations via Prophet (a type of time series forecasting model), and input the data using the programming language Python.

Further insight vs compromised privacy

Combining predictions generated through AI with big data, and location-based services such as GPS tracking, can provide targeted insight on the movements of people diagnosed with COVID-19.

Read more: Why public health officials sound more worried about the coronavirus than the seasonal flu

This information would help governments implement effective contingency plans, and prevent the virus’s spread.

We saw this happen in China, where telecommunication providers used location tracking to alert the Chinese government of the movements of people in quarantine. However, such methods raise obvious privacy issues.

Honing in on smaller areas

In our analysis, we only considered worldwide data. If localised data becomes available, we could identify which countries, cities and even suburbs are more vulnerable to COVID-19 than others.

We already know different regions are likely to experience different growth rates of COVID-19. This is because the virus’ spread is influenced by many factors, including speed of diagnoses, government response, population density, quality of public healthcare and local climate.

As the COVID-19 outbreak expands, the world’s collective response will render our model susceptible to variation. But until the virus is controlled and more is learned about it, we believe forewarned is forearmed.

Read more: Coronavirus: How behaviour can help control the spread of COVID-19

Correction: previously this article said the author’s model could predict COVID-19 infections to an accuracy of 96%, and deaths to an accuracy of 99%, up to one week into the future. This was incorrect and has been amended.

Authors: Belal Alsinglawi, PhD Candidate in Data Science and ICT Lecturer, Western Sydney University