'Slow-minded and bewildered': Donald Trump builds barriers to peace and prosperity

- Written by John Hawkins, Assistant Professor, School of Politics, Economics and Society, University of Canberra

The US president “had no plan, no scheme, no constructive ideas whatever”, according to one of the world’s most influential economists.

He was “in many respects, perhaps inevitably, ill-informed”. He was “slow-minded and bewildered”, and failed to remedy these defects by seeking advice. He gathered around him businessmen, “inexperienced in public affairs” and “only called in irregularly”.

This assessment was written a century ago, in 1919, by the up-and-coming economist John Maynard Keynes.

The president was Woodrow Wilson, whom Keynes criticised for his inability to influence Europe’s post-first world war settlement in a way more likely to lead to peace and prosperity.

A century later the United States has another president out of his depth in global affairs. Wilson, at least, was a “generously intentioned” man. What would Keynes make of Donald Trump, whose policies are driven by a sense of entitlement and fear of being played for a sucker?

This week, at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Trump flagged new fronts in his dangerous campaign of economic nationalism. He reaffirmed his intention to reshape the World Trade Organization, which he said been “very unfair to the United States for many, many years”.

He fretted about the “tremendous advantages” given to China and India. He threatened tariffs on European cars if the European Union didn’t agree to a “fair” free-trade deal.

The barrier-besotted president is pretty much everything Keynes warned against as ruinous to the prospects of a lasting peace.

A tale of two presidents

Keynes had observed Wilson at the talks in Paris to conclude the Treaty of Versailles, which set out the detail of terms and conditions following Germany’s surrender (on November 11 1918) to end the war.

Wilson had proposed 14 points for a “just and stable peace” but proved completely ineffectual at the talks. The result was a treaty with terms so punitive for Germany they arguably created the conditions for Adolf Hitler to come to power, and thus led to the second world war.

Keynes’s disquiet with the treaty led him to write the book The Economic Consequences of the Peace.

Wilson’s great failure was his inability to prevent punitive action. Trump’s is his love of punitive action. If his default stance in international diplomacy was to be summed up in a three-word slogan, it would be “Make Them Pay”.

In the longer term his administration’s intransigence on climate change may well prove Trump’s worst policy legacy to the world. But right now he is doing most damage through bringing back tariffs, particularly in the trade war started with China.

Trump has claimed (more than a hundred times in 2019, by one count) that he has made China pay by imposing tariffs on Chinese exports to the US. The truth, of course, is that US import tariffs “were almost completely passed through into US domestic prices”. China pays through its goods being less competitive.

Trade war costs

Trump has bragged just as loudly about winning the peace. A week ago he declared a “phase one” trade deal as “the biggest deal anybody has ever seen”.

But really all this agreement does is reverse some of the harmful actions the US has taken. It has been aptly called a “partial and defective” truce.

This week the International Monetary Fund (IMF) updated modelling first published in October 2019 estimating the damage the US-China trade war will do in 2020.

Its initial modelling estimated the tit-for-tat tariffs would reduce the level of global GDP in 2020 by 0.8 percentage points. Trump’s “biggest deal anybody has ever seen” will reduce that harm, but by just 0.3 percentage points, meaning world growth will be 3.3%, rather than 3.8% in 2020. And that’s only, says IMF chief economist Gita Gopinath, if the deal proves durable.

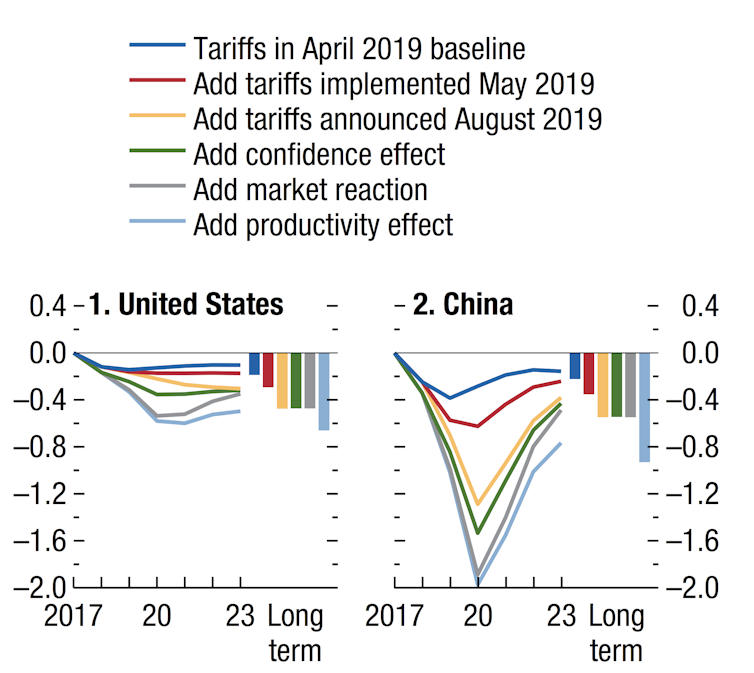

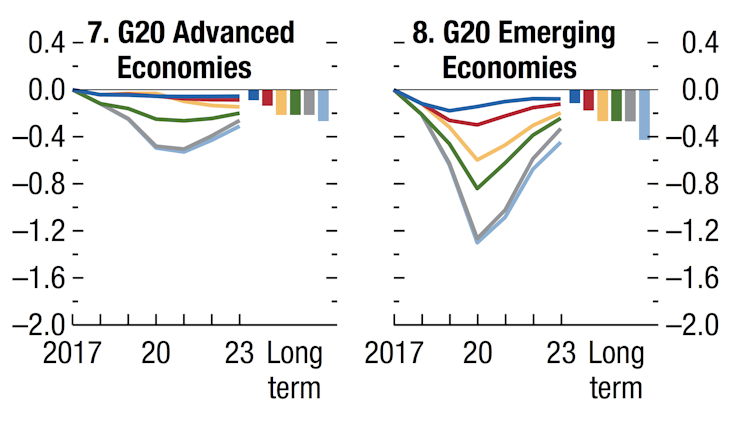

The IMF’s October 2019 modelling included a breakdown of how much various economies would suffer in 2020 from the trade war. It estimated China’s real GDP would be 2 percentage points lower than otherwise, with the US down 0.6 percentage points. Europe and Japan would lose about 0.5 percentage points.

IMF, World Economic Outlook, October 2019

IMF, World Economic Outlook, October 2019

IMF estimates of the effect of US-China trade barriers.

IMF World Economic Outlook, October 2019

China’s economy is growing at three times the rate of the US – an estimated 6% compared with 2% – so the hit is almost equal. In terms of lost GDP per capita – a proxy measure for how much the tariffs cost individuals on average – the cost is about US$400 a year for both US and Chinese citizens.

Given China’s median income is well below that of the US, that forgone extra income hurts more in China – something fitting the Trumpian narrative that the trade war is making China pay more.

But the lesson of history is that punitive actions come back to bite. As Keynes so eloquently wrote a century ago, “the prosperity and happiness of one country promotes that of others”.

Read more:

What's worse than the US-China trade war? A grand peace bargain

Crucial to peace and prosperity, Keynes said, was free trade, which he hoped could mitigate the adverse “new political frontiers now created between greedy, jealous, immature, and economically incomplete nationalist States”.

Wilson aspired but failed to replace a world order based on conflict between great powers with one based on rules and reason. Trump, by contrast, seems to prefer conflict over rules and reason.

A punitive approach to international economic relations failed a century ago. We have good reason to fear it now.

IMF estimates of the effect of US-China trade barriers.

IMF World Economic Outlook, October 2019

China’s economy is growing at three times the rate of the US – an estimated 6% compared with 2% – so the hit is almost equal. In terms of lost GDP per capita – a proxy measure for how much the tariffs cost individuals on average – the cost is about US$400 a year for both US and Chinese citizens.

Given China’s median income is well below that of the US, that forgone extra income hurts more in China – something fitting the Trumpian narrative that the trade war is making China pay more.

But the lesson of history is that punitive actions come back to bite. As Keynes so eloquently wrote a century ago, “the prosperity and happiness of one country promotes that of others”.

Read more:

What's worse than the US-China trade war? A grand peace bargain

Crucial to peace and prosperity, Keynes said, was free trade, which he hoped could mitigate the adverse “new political frontiers now created between greedy, jealous, immature, and economically incomplete nationalist States”.

Wilson aspired but failed to replace a world order based on conflict between great powers with one based on rules and reason. Trump, by contrast, seems to prefer conflict over rules and reason.

A punitive approach to international economic relations failed a century ago. We have good reason to fear it now.

Authors: John Hawkins, Assistant Professor, School of Politics, Economics and Society, University of Canberra