New study: changes in climate since 2000 have cut Australian farm profits 22%

- Written by Neal Hughes, Senior Economist, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES)

The current drought across much of eastern Australia has demonstrated the dramatic effects climate variability can have on farm businesses and households.

The drought has also renewed longstanding discussions around the emerging effects of climate change on agriculture, and how governments can best help farmers to manage drought risk.

A new study released this morning by the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences offers fresh insight on these issues by quantifying the impacts of recent climate variability on the profits of Australian broadacre farms.

Read more: Droughts, extreme weather and empowered consumers mean tough choices for farmers

The results show that changes in temperature and rainfall over the past 20 years have had a negative effect on average farm profits while also increasing risk.

The findings demonstrate the importance of adaptation, innovation and adjustment to the agriculture sector, and the need for policy responses which promote – and don’t unnecessarily inhibit – such progress.

Measuring the effects of climate on farms

Measuring the effects of climate on farms is difficult given the many other factors that also influence farm performance, including commodity prices.

Further, the effects of rainfall and temperature on farm production and profit can be complex and highly location and farm specific.

To address this complexity, ABARES has developed a model based on more than 30 years of historical farm and climate data—farmpredict — which can identify effects of climate variability, input and output prices, and other factors on different types of farms.

Cropping farms most exposed

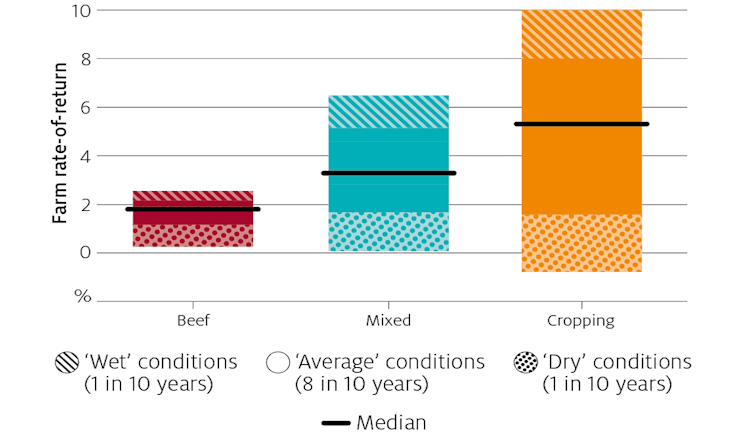

The model finds that cropping farms generally face greater climate risk than beef farms, but also generate higher average returns.

Cropping farm revenue and profits are lower in dry years, with large reductions in crop yields and only small savings in input costs.

Effect of climate variability on rate of return

Based on historical climate conditions (1950 to 2019), holding non-climate factors constant. See report for more detail. ABARES FarmPredict

In contrast, drought has a smaller immediate effect on beef farm revenue, because in dry years farmers can increase the quantity of livestock sold.

However, drought also lowers herd numbers, which lowers farm profit when herd value is accounted for.

Higher temperatures, lower winter rainfall

Australian average temperatures have increased by about 1°C since 1950.

Recent decades have also seen a trend towards lower average winter rainfall in the southwest and southeast.

This drying trend has been linked to atmospheric changes associated with global warming.

However, while global climate models generally predict a decline in winter season rainfall across southern Australia and more time spent in drought, there is still much uncertainty about what will happen in the long term, particularly to rainfall.

Climate shifts have cut farm profits

ABARES has assessed the effect of climate variability on farm profits over the period 1950 to 2019, holding all other factors constant including commodity prices and farm management practices.

We find that the shift in climate conditions since 2000 (from conditions in the period 1950-1999 to conditions in the period 2000-2019) has had a negative effect on the profits of both cropping and livestock farms.

Effect of 2000 - 2019 climate conditions on average farm profit

Based on historical climate conditions (1950 to 2019), holding non-climate factors constant. See report for more detail. ABARES FarmPredict

In contrast, drought has a smaller immediate effect on beef farm revenue, because in dry years farmers can increase the quantity of livestock sold.

However, drought also lowers herd numbers, which lowers farm profit when herd value is accounted for.

Higher temperatures, lower winter rainfall

Australian average temperatures have increased by about 1°C since 1950.

Recent decades have also seen a trend towards lower average winter rainfall in the southwest and southeast.

This drying trend has been linked to atmospheric changes associated with global warming.

However, while global climate models generally predict a decline in winter season rainfall across southern Australia and more time spent in drought, there is still much uncertainty about what will happen in the long term, particularly to rainfall.

Climate shifts have cut farm profits

ABARES has assessed the effect of climate variability on farm profits over the period 1950 to 2019, holding all other factors constant including commodity prices and farm management practices.

We find that the shift in climate conditions since 2000 (from conditions in the period 1950-1999 to conditions in the period 2000-2019) has had a negative effect on the profits of both cropping and livestock farms.

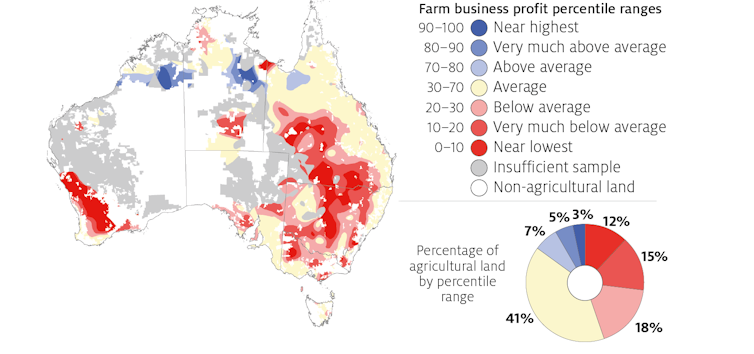

Effect of 2000 - 2019 climate conditions on average farm profit

"Farm profit percentiles for the period 2000-2019 relative to 1950-1999, holding non-climate factors constant. See report for more detail. ABARES

We estimate that the shift in climate has cut average annual broadacre farm profits by around 22%, which is an average of $18,600 per farm per year, controlling for all other factors.

The effects have been most pronounced in the cropping sector, reducing average profits by 35%, or $70,900 a year for a typical cropping farm.

At a national level this amounts to an average loss in production of broadacre crops of around $1.1 billion a year.

Although beef farms have been less affected than cropping farms overall, some beef farming regions have been affected more than others, especially south-western Queensland.

Read more:

Drought is inevitable, Mr Joyce

Like previous ABARES research this study finds evidence of adaptation, with farmers reducing their sensitivity to dry conditions over time.

Our results suggest that without this adaptation the effects of the post-2000 climate shift would have been considerably larger, particularly for cropping farms.

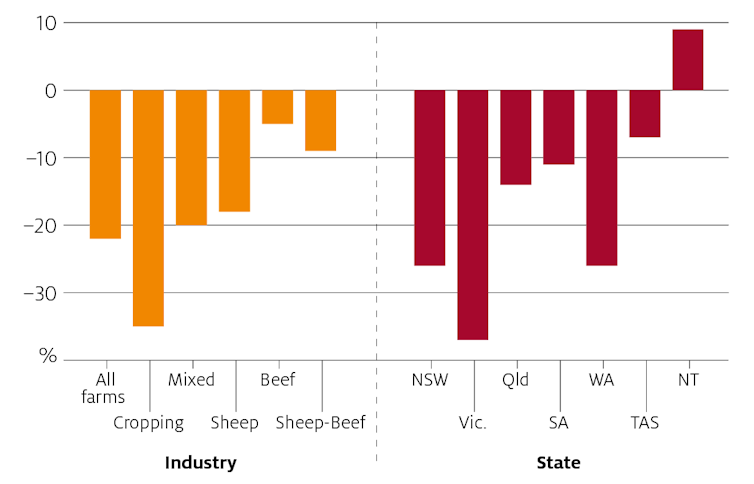

Effect of post-2000 climate on average annual farm profits

"Farm profit percentiles for the period 2000-2019 relative to 1950-1999, holding non-climate factors constant. See report for more detail. ABARES

We estimate that the shift in climate has cut average annual broadacre farm profits by around 22%, which is an average of $18,600 per farm per year, controlling for all other factors.

The effects have been most pronounced in the cropping sector, reducing average profits by 35%, or $70,900 a year for a typical cropping farm.

At a national level this amounts to an average loss in production of broadacre crops of around $1.1 billion a year.

Although beef farms have been less affected than cropping farms overall, some beef farming regions have been affected more than others, especially south-western Queensland.

Read more:

Drought is inevitable, Mr Joyce

Like previous ABARES research this study finds evidence of adaptation, with farmers reducing their sensitivity to dry conditions over time.

Our results suggest that without this adaptation the effects of the post-2000 climate shift would have been considerably larger, particularly for cropping farms.

Effect of post-2000 climate on average annual farm profits

Per cent change relative to 1950-1999 climate, holding non-climate factors constant. See report for more detail. ABARES FarmPredict

Risk and income volatility have also increased

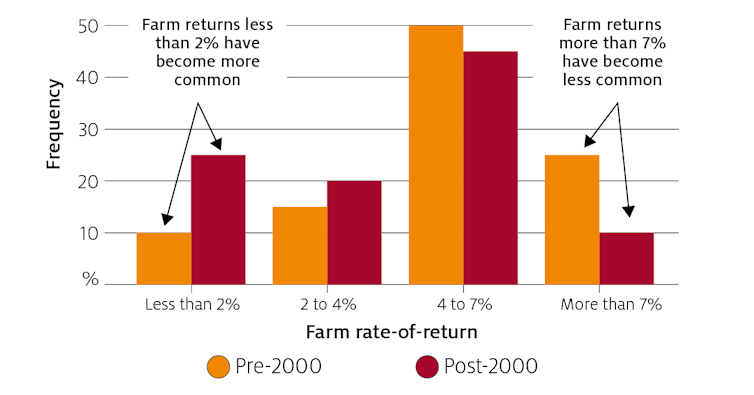

The changed climate conditions since 2000 have also increased risk and income volatility.

This is particularly so for cropping farms, where we find the chance of low-profit years has more than doubled as a result of the change in climate conditions.

Effect of climate variability on typical cropping farm

Per cent change relative to 1950-1999 climate, holding non-climate factors constant. See report for more detail. ABARES FarmPredict

Risk and income volatility have also increased

The changed climate conditions since 2000 have also increased risk and income volatility.

This is particularly so for cropping farms, where we find the chance of low-profit years has more than doubled as a result of the change in climate conditions.

Effect of climate variability on typical cropping farm

Distribution of farm profits for 1950-1999 climate and 2000-2019 climate. See report for more detail. ABARES FarmPredict

Handle with care – the drought policy dilemma

Drought policy faces an almost unavoidable dilemma, that providing relief to farm businesses and households in times of drought risks slowing industry structural adjustment and innovation.

Adjustment, change and innovation are fundamental to improving agricultural productivity; maintaining Australia’s competitiveness in world markets; and providing attractive and financially sustainable opportunities for farm households.

Read more:

Helping farmers in distress doesn't help them be the best: the drought relief dilemma

For these reasons, the strategic intent of drought policy has shifted away from seeking to protect and insulate farmers towards the promotion of drought preparedness and self‑reliance.

The best options for reconciling the drought policy dilemma focus on boosting the resilience of farm businesses and households to future droughts and climate variability, including through action and investment when farmers are not in drought.

The government’s Future Drought Fund, which will support research and innovation, is a good example of this approach.

Developing new insurance options is one worthwhile avenue of research which could provide farmers a way to self-manage risk. It would require investments in data and knowledge to support viable weather insurance markets: where farmers pay premiums sufficient to cover costs over time.

Read more:

Better data would help crack the drought insurance problem

Supporting farm households experiencing hardship is legitimate and important, but for the long term health of the farm sector this needs to be done in ways that promote resilience and improved productivity and allow for long term adjustment to change.

Distribution of farm profits for 1950-1999 climate and 2000-2019 climate. See report for more detail. ABARES FarmPredict

Handle with care – the drought policy dilemma

Drought policy faces an almost unavoidable dilemma, that providing relief to farm businesses and households in times of drought risks slowing industry structural adjustment and innovation.

Adjustment, change and innovation are fundamental to improving agricultural productivity; maintaining Australia’s competitiveness in world markets; and providing attractive and financially sustainable opportunities for farm households.

Read more:

Helping farmers in distress doesn't help them be the best: the drought relief dilemma

For these reasons, the strategic intent of drought policy has shifted away from seeking to protect and insulate farmers towards the promotion of drought preparedness and self‑reliance.

The best options for reconciling the drought policy dilemma focus on boosting the resilience of farm businesses and households to future droughts and climate variability, including through action and investment when farmers are not in drought.

The government’s Future Drought Fund, which will support research and innovation, is a good example of this approach.

Developing new insurance options is one worthwhile avenue of research which could provide farmers a way to self-manage risk. It would require investments in data and knowledge to support viable weather insurance markets: where farmers pay premiums sufficient to cover costs over time.

Read more:

Better data would help crack the drought insurance problem

Supporting farm households experiencing hardship is legitimate and important, but for the long term health of the farm sector this needs to be done in ways that promote resilience and improved productivity and allow for long term adjustment to change.

Authors: Neal Hughes, Senior Economist, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES)