Happy Sad Man: a small, gentle, important film that reveals the vulnerability of men

- Written by Scott McKinnon, Vice-Chancellor's Postdoctoral Research Fellow, University of Wollongong

Review: Happy Sad Man, directed by Genevieve Bailey

“I am just me. Put that on the big screen. I’ve got a mental illness. So have you.”

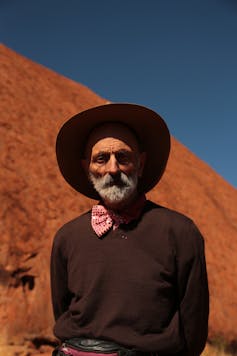

The above is a quote from John, one of five men whose lives filmmaker Genevieve Bailey explores in her documentary Happy Sad Man. Bailey’s hand-held camera moves in close on John’s hard-lined face as he makes this statement. His emotions are hard to read. Sad, defiant, amused. In voice-over, Bailey describes John as “the happiest and saddest man I’ve ever met.”

John provided inspiration for the film.

Photo: Genevieve Bailey

John provided inspiration for the film.

Photo: Genevieve Bailey

The question of how men “navigate the dance between happiness and sadness” is the film’s core concern. Each of the lives through which Bailey explores that question is impacted by mental illness.

John has been diagnosed with bipolar disorder, as has surfer Grant. David, an artist, experiences anxiety. Jake has worked as a photographer and community worker in war zones and has been diagnosed with PTSD. Ivan is a farmer who works with rural men’s health groups, offering an empathetic ear to men who need to talk and explaining, “It’s pretty scary, I reckon, how vulnerable we all are.”

Bailey has friendships with each of the five and has, over several years, recorded extensive conversations with them all, as well as moments with their families and friends. The result is a kind and gentle film with empathy at its heart. Happy Sad Man makes a case for talking, listening and simply “being with” as valuable acts of care.

Happy Sad Man trailer.In so doing, the film seeks to disrupt a commonly held idea that men do not want to talk about their emotions. Bailey states that, in her experience, “the opposite is true.”

Each of the five men Bailey interviews is extremely articulate in describing their experiences with mental illness. She also meets an older man at a rural Men’s Shed whom knows she is making a film about mental illness and want to ask her questions. It’s not that he doesn’t want to talk, it seems, but rather that he has previously lacked the language and the opportunities for doing so.

Optimism

The film is intrinsically optimistic, revealing increasing openings for conversation created through acts of empathy, kindness, whimsy and joy. This isn’t to say Bailey downplays the impacts of mental illness. She records John in the midst of a depressive episode so severe he is hospitalised for several weeks. It’s heartbreaking, difficult viewing. Also suggested – if mostly obliquely – are the ways in which John’s illness has harmed his relationships with family and friends through the course of his life.

Bailey makes the argument, however, that old forms of masculinity are being resisted or challenged, producing new opportunities for better treatment. John tells her, “I was brought up in the school that you tough it out son, you tough it out. You’re a wuss.”

Happy, Sad Man reveals strategies deployed by her subjects to resist such limiting and harmful views of masculinity, celebrating these acts of resistance as indicative of important progress.

Grant, for example, has organised a weekly surf event called Fluro Friday where participants dress in fluorescent clothes, creating humorous, cheerfully offbeat spaces in which to discuss mental health. David, who describes masculinity as “quite banal, really”, creates art that is witty and revels in its own eccentricity. These deliberate disruptions celebrate – rather than fear – men’s difference, openness and vulnerability.

Jake, another friend of Bailey’s in the film, battles PTSD.

Photo: Ben McNamara

Jake, another friend of Bailey’s in the film, battles PTSD.

Photo: Ben McNamara

These acts are worth celebrating, as are improvements in health care. I found the film’s optimism admirable and valuable, while at times wondering if ongoing and harmful patriarchal structures were being overlooked or downplayed.

Limitations

There is an intimacy to the film’s scope that is both a limitation and a strength. Issues of indigeneity, sexuality and gender identity, for example, each of which is known to potentially exacerbate the impacts of mental illness, are not explored.

Ongoing questions about the funding of mental healthcare are not addressed.

And amid arguments about men’s ability and desire to discuss their emotions, I was left wondering about workplace and other environments that continue to limit the kinds of shifts away from macho culture the film celebrates.

At a moment, though, in which (justifiable) anger and brutal debate dominate so much of our collective conversations, this small, gentle film feels important.

As viewers, we might feel uncomfortable with Bailey’s camera recording her subjects in moments of despair. But in doing so, both filmmaker and subject resist the shaming that seeks to define these moments as unspeakable or hidden.

Happy Sad Man reveals the vulnerability of men dealing with mental illness and creates a space for radical kindness.

Authors: Scott McKinnon, Vice-Chancellor's Postdoctoral Research Fellow, University of Wollongong