Hot as shell: birds in cooler climates lay darker eggs to keep their embryos warm

- Written by Phill Cassey, Assoc Prof in Invasion Biogeography and Biosecurity, University of Adelaide

Birds lay eggs with a huge variety of colours and patterns, from immaculate white to a range of blue-greens and reddish browns.

The need to conceal eggs from predators is one factor that gives rise to all kinds of camouflaged and hard-to-spot appearances.

Yet our research, published today in Nature Ecology & Evolution, shows that climate is even more important.

Dark colours play a crucial role in regulating temperatures in many biological systems. This is particularly common for animals like reptiles, which rely on environmental sources of heat to keep themselves warm.

Read more: Curious Kids: why do eggs have a yolk?

Darker colours absorb more heat from sunlight, and animals with these colours are more commonly found in colder climates with less sunlight. This broad pattern is known as Bogert’s rule.

Birds’ eggs are useful for studying this pattern because the developing embryo can only survive in a narrow range of temperatures. But eggs cannot regulate their own temperature and, in most cases, the parent does it by sitting atop the clutch of eggs.

In colder environments, where the risk of predators is lower and the risk of chilling in cold temperatures is greater, parents spend less time away from the nest.

We predicted that if eggshell colour does play an important role in regulating the temperature of the embryo, birds living in colder environments should have darker eggs.

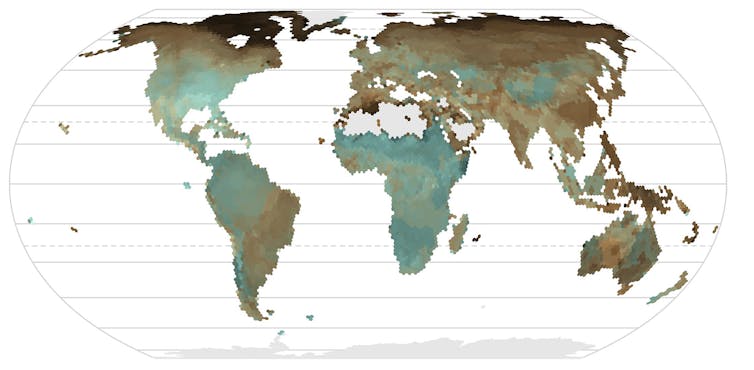

The average colour of eggshells in different areas around the world.

Wisocki et al. 2019 'The global distribution of avian eggshell colours suggests a thermoregulatory benefit of darker pigmentation', Nature Ecology & Evolution, Author provided

The average colour of eggshells in different areas around the world.

Wisocki et al. 2019 'The global distribution of avian eggshell colours suggests a thermoregulatory benefit of darker pigmentation', Nature Ecology & Evolution, Author provided

To test the prediction, we measured eggshell brightness and colour for 634 species of birds. That’s more than 5% of all bird species, representing 36 of the 40 large groups of species called orders.

We mapped these within each species’ breeding range and found that eggs in the coldest environments (those with the least sunlight) were significantly darker. This was true for all nest types.

We also conducted experiments using domestic chicken eggs to confirm that darker eggshells heated up more rapidly and maintained their incubation temperatures for longer than white eggshells.

Read more: It isn't easy being blue – the cost of colour in fairy wrens

Our results show that darker eggshells are found in places with less sunlight and lower temperatures, and that these darker colours may help keep the developing embryo warm.

How future climate change will affect eggshell appearance, as well as the timing of reproduction and incubation behaviour, will be an important and fruitful avenue for future research.

Authors: Phill Cassey, Assoc Prof in Invasion Biogeography and Biosecurity, University of Adelaide