Environment laws have failed to tackle the extinction emergency. Here's the proof

- Written by Michelle Ward, PhD Student, The University of Queensland

Threatened species habitat larger than the size of Tasmania has been destroyed since Australia’s environment laws were enacted, and 93% of this habitat loss was not referred to the federal government for scrutiny, our new research shows.

The research, published today in Conservation Science and Practice, shows that 7.7 million hectares of threatened species habitat has been destroyed in the 20 years since the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act 1999 came into force.

The Southern black throated finch, one of the threatened native animals worst affected by habitat loss.

Eric Vanderduys/BirdLife Australia

The Southern black throated finch, one of the threatened native animals worst affected by habitat loss.

Eric Vanderduys/BirdLife Australia

Read more: Koalas can learn to live the city life if we give them the trees and safe spaces they need

Some 85% of land-based threatened species experienced habitat loss. The iconic koala was among the worst affected. More than 90% of habitat loss was not referred or submitted for assessment, despite a requirement to do so under Commonwealth environment laws.

Our research indicates the legislation has comprehensively failed to safeguard Australia’s globally significant natural values, and must urgently be reformed and enforced.

What are the laws supposed to do?

The EPBC Act was enacted in 1999 to protect the diversity of Australia’s unique, and increasingly threatened, flora and fauna. It was considered a giant step forward for biodiversity conservation and was expected to become an important legacy of the Howard Coalition government.

A dead koala outside Ipswich, Queensland. Environmentalists attributed the death to land clearing.

Jim Dodrill/The Wilderness Society

A dead koala outside Ipswich, Queensland. Environmentalists attributed the death to land clearing.

Jim Dodrill/The Wilderness Society

Read more: Queensland's new land-clearing laws are all stick and no carrot (but it's time to do better)

The law aims to conserve so-called “protected matters” such as threatened species, migratory species, and threatened ecosystems.

Clearing and land use change is regarded by ecologists as the primary threat to Australia’s biodiversity. In Queensland, land clearing to create pasture is the greatest pressure on threatened flora and fauna.

Any action which could have a significant impact on protected matters, including habitat destruction through land clearing, must be referred to the federal government for assessment.

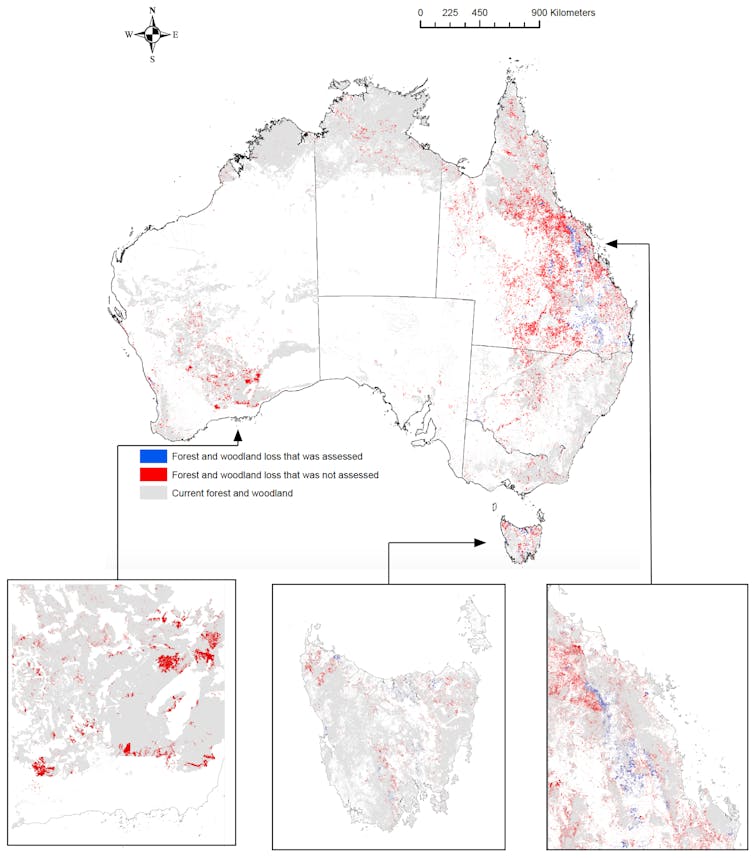

Loss of potential habitat for threatened species and migratory species, and threatened ecological communities. Dark blue represents habitat loss that has been assessed (or loss that occurred with a referral under the EPBC Act) and dark red represents habitat loss that has not been assessed (or loss that occurred without a referral under The Act). Three panels highlight the southern Western Australia coast (left), Tasmania (middle), and northern Queensland coast (right).

Adapted from Ward et al. 2019

Loss of potential habitat for threatened species and migratory species, and threatened ecological communities. Dark blue represents habitat loss that has been assessed (or loss that occurred with a referral under the EPBC Act) and dark red represents habitat loss that has not been assessed (or loss that occurred without a referral under The Act). Three panels highlight the southern Western Australia coast (left), Tasmania (middle), and northern Queensland coast (right).

Adapted from Ward et al. 2019

The law is not being followed

We examined federal government forest and woodland maps derived from satellite imagery. The analysis showed that 7.7 million hectares of threatened species habitat has been cleared or destroyed since the legislation was enacted.

Of this area, 93% was not referred to the federal government and so was neither assessed nor approved.

Bulldozer clearing trees at Queensland’s Olive Vale Station in 2015.

ABC News, 2017

Bulldozer clearing trees at Queensland’s Olive Vale Station in 2015.

ABC News, 2017

It is unclear why people or companies are not referring habitat destruction on such a large scale. People may be self-assessing their activities and concluding they will not have a significant impact.

Others may be seeking to avoid the expense of a referral, which costs A$6,577 for people or companies with a turnover of more than A$10 million a year.

The failure to refer may also indicate a lack of awareness of, or disregard for, the EPBC Act.

The biggest losers

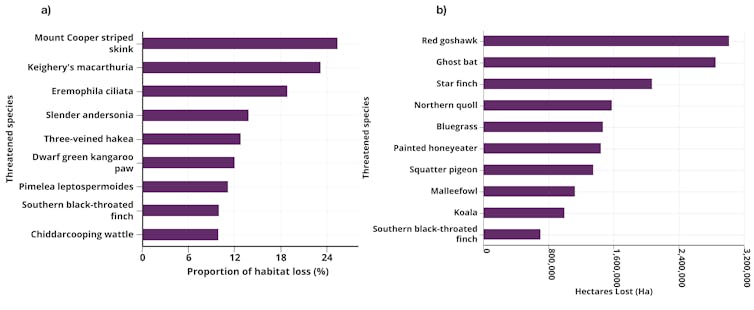

Our research found that 1,390 (85%) of terrestrial threatened species experienced habitat loss within their range since the EPBC Act was introduced.

Among the top ten species to lose the most area were the red goshawk, the ghost bat, and the koala, losing 3 million, 2.9 million, and 1 million hectares, respectively.

In less than two decades, many other imperilled species have lost large chunks of their potential habitat. They include the Mount Cooper striped skink (25%), the Keighery’s macarthuria (23%) and the Southern black-throated finch (10%).

(a) The top 10 most severely impacted threatened species include those that have lost the highest proportion of their total habitat, and (b) species who have lost the most habitat, as mapped by the Federal Government.

Adapted from Ward et al. 2019

(a) The top 10 most severely impacted threatened species include those that have lost the highest proportion of their total habitat, and (b) species who have lost the most habitat, as mapped by the Federal Government.

Adapted from Ward et al. 2019

What’s working, what’s not

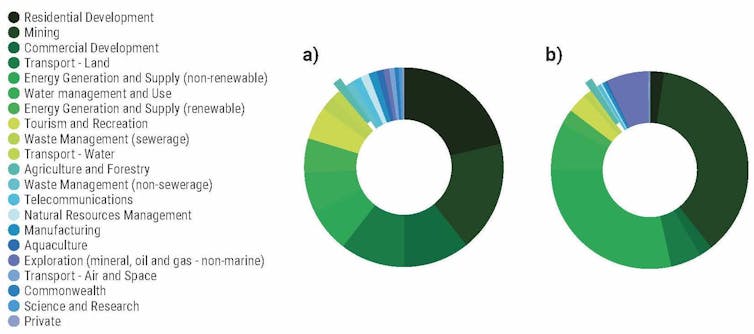

We found that almost all referrals to the federal government for habitat loss were made by urban developers, mining companies and commercial developers. A tiny 1.3% of referrals were made by agricultural developers - despite clear evidence that land clearing for pasture development is the primary driver of habitat destruction.

Alarmingly, even when companies or people did refer proposed actions, 99% were allowed to proceed (sometimes with conditions).

The high approval rates may be derived, in part, from inconsistent application of the “significance” test under the federal laws.

Hundreds of protesters gather in Sydney in 2016 to demand that New South Wales retain strong land clearing laws.

Dean Lewins/AAP

Hundreds of protesters gather in Sydney in 2016 to demand that New South Wales retain strong land clearing laws.

Dean Lewins/AAP

For example, in a successful prosecution in 2015, Powercor Australia and Vemco] were fined A$200,000 for failing to refer clearing of a tiny 0.5 hectares of a critically endangered ecosystem. In contrast, much larger tracts of habitat have been destroyed without referral or approval, and without any such enforcement action being taken.

Clearer criteria for determining whether an impact is significant would reduce inconsistency in decisions, and provide more certainty for stakeholders.

The laws must be enforced and reformed

If the habitat loss trend continues, two things are certain: more species will become threatened with extinction, and more species will become extinct.

The Act must, as a matter of urgency, be properly enforced to curtail the mass non-referral of actions that our analysis has revealed.

The left pie chart illustrates the breakdown of industries referring their actions by number of referrals; the right pie chart illustrates the breakdown of industries referring their actions by area (hectares). Both charts highlight the agricultural sector as a low-referring industry.

Adapted from Ward et al. 2019

The left pie chart illustrates the breakdown of industries referring their actions by number of referrals; the right pie chart illustrates the breakdown of industries referring their actions by area (hectares). Both charts highlight the agricultural sector as a low-referring industry.

Adapted from Ward et al. 2019

If nothing else, this will help Australia meet its commitment under the Convention on Biological Diversity to prevent extinction of known threatened species and improve their conservation status by 2020.

Read more: Why aren't Australia's environment laws preventing widespread land clearing?

Mapping the critical habitat essential to the survival of every threatened species is also an important step. The Act should also be reformed to ensure critical habitat is identified and protected, as happens in the United States.

Australia is already a world leader in modern-day extinctions. Without a fundamental change in how environmental law is written, used, and enforced, the crisis will only get worse.

Authors: Michelle Ward, PhD Student, The University of Queensland