Flexible working, the neglected congestion-busting solution for our cities

- Written by John L Hopkins, Theme Leader (Future Urban Mobility), Smart Cities Research Institute, Swinburne University of Technology

Traffic congestion is one of the most significant challenges facing our cities. Melbourne’s population is growing by around 325 people a day and is projected to overtake Sydney’s within a decade. Identified as the most congested city in the country, this was a factor in Melbourne losing its seven-year grip on the “world’s most liveable city” title last year.

One obvious solution to traffic congestion, caused mostly by workers commuting to jobs in the city centre during peak hours, might appear to be building more, or bigger, roads. But a less obvious answer, and potentially a more cost-effective one, might be to increase flexible working arrangements.

Our research has looked into ways to ease congestion by reducing the need for travel in congested areas in the first place. It shows city workers definitely have an appetite for flexible work hours and practices.

However, many (36%) still can’t or don’t work remotely. Those who do work remotely do so for a small fraction of the week – 1.1 days on average – even though a high percentage of their work tasks can be done anywhere.

More roads don’t solve the problem

Traditionally, congestion has simply been accepted as the starting point, with infrastructure being built to accommodate it. However, as a report on US research findings about so-called induced demand explains:

If you expand people’s ability to travel, they will do it more. […] Making driving easier means that people take more trips in the car than they otherwise would.

This increase in travel uses up any extra capacity improved infrastructure might bring. As a result, traffic levels and congestion remain constant.

A 2019 report from Infrastructure Australia observes that the huge number of road and rail projects in Sydney and Melbourne, both current and planned, will not prevent crippling congestion by 2031.

Read more: Do more roads really mean less congestion for commuters?

What did the flexible working study find?

This issue was the motivation for our study into alternative ways to ease congestion. It identified flexible working as one possible solution.

The term flexible working refers to arrangements that enable employees to adjust the number of hours they work, the pattern of those hours, or where they work. Flexible working has risen significantly in recent years, with many potential benefits for both employees and employers. Yet few studies have examined its potential to reduce traffic congestion.

Read more: Working four-day weeks for five days' pay? Research shows it pays off

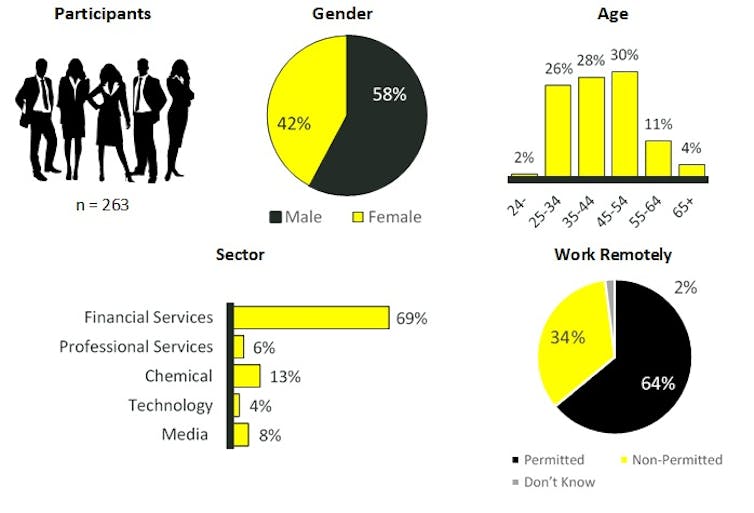

For our study, we surveyed 263 city workers from ten of Melbourne’s biggest employers. We asked them about their commuting habits, existing flexible working arrangements, attitudes toward flexible working and the nature of their work tasks.

We found 64% of workers were already taking advantage of some sort of flexible working arrangements that allowed them to work from a remote location, usually at home, an average of 1.1 days a week. And 83% of them either “liked” or “loved” the ability to do this.

Only 2% said none of their work could be performed from an alternative location. A majority of participants, 58%, indicated they could do at least half their work duties out of the office. Some 30% of the workers indicated 80% or more of their work duties could be performed remotely.

Breakdown of participants in flexible working survey.

Author's research, Author provided

Breakdown of participants in flexible working survey.

Author's research, Author provided

Technology enables these flexible working opportunities. Laptops, smartphones, high-speed internet and cloud access were highlighted as the must-haves for remote working.

Many of us no longer need to travel to a fixed location to work because the tools of our labour are located there. The tools of our labour are now in our back pockets or work satchels.

Finland shows what’s possible

Urban congestion is a growing problem worldwide. Today, 55% of people live in urban areas, a figure expected to reach 68% by 2050. The use of motor vehicles is also growing rapidly.

But access to flexible working is growing around the world too.

Finland, a pioneer of flexible working practices, recently adopted a new Working Hours Act. It will give a majority of full-time employees the right to decide when and where they work for at least half of their working hours.

A similar flexible working bill was introduced to the UK Parliament in July by Conservative MP Helen Whately. She said:

The 40-hour, five-day working week made sense in an era of single-earner households and stay-at-home mums, but it no longer reflects the reality of how many modern families want to live their lives.

Our evidence from Melbourne suggests the appetite for, and availability of, flexible working will continue to increase as more people do it and more millennials take up leadership roles.

A small reduction in peak-hour commuter numbers could make the difference between being able to squeeze onto a train or not.

Runs With Scissors/Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND

A small reduction in peak-hour commuter numbers could make the difference between being able to squeeze onto a train or not.

Runs With Scissors/Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND

If the 64% of workers who now work remotely 1.1 days a week increased this to five days a fortnight, this could cut the number of daily commuters to Melbourne from 572,000 to 440,500 a day. If the remaining 36% of workers were also able to work remotely 50% of the time, daily commuter numbers would fall further to around 337,500, a total reduction of 41%.

Even much smaller reductions in commuter numbers could have significant impacts on congestion. An NRMA submission that advocated flexible working hours and practices to a 2013 NSW parliamentary inquiry noted:

As a rule of thumb, when traffic on congested roads reduces by 5%, traffic speeds increase 50% (even if this only means going from 20 to 30km/h) […] A small reduction in the amount of passengers during peak hours can sometimes make the difference between being able to squeeze onto a bus or train, or not.

In this era of growing urban congestion, an increase in flexible working practices appears to have serious potential for easing the strain on our roads and transport networks. Isn’t it about time we asked ourselves if we could all be a bit more flexible?

Authors: John L Hopkins, Theme Leader (Future Urban Mobility), Smart Cities Research Institute, Swinburne University of Technology