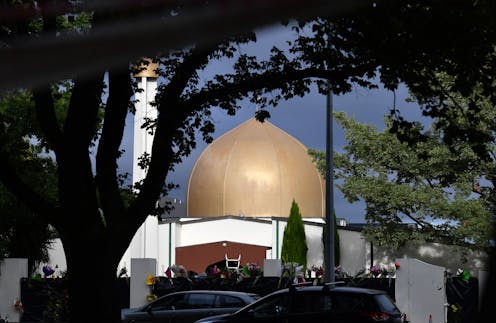

Establishing fitness to stand trial as the first step in Christchurch attack court process

- Written by Alexander Gillespie, Professor of Law, University of Waikato

The first question that will have to be answered before the case against the alleged perpetrator of the Christchurch mosque attacks can proceed is whether he is fit to stand trial.

When there is no debate about whether a specific person carried out an act of mass murder, the question of whether they are mad or bad provokes difficult discussions.

But the conclusion matters. While the insane are not legally responsible for what they do, the sane are.

Read more: Explainer: how a royal commission will investigate Christchurch shootings

Terrorists are often not crazy

When mass murderers are not part of any political group and are killed in their attack, such as the Las Vegas shooter who killed 59 unarmed civilians in 2017, many may have nodded in agreement when President Donald Trump described him as a “very, very sick individual”.

Others will be sceptical of such classifications, especially when there is no history of mental illness and the attacks reflect a degree of sophistication and planning. The sceptics will also point out that a label of mad, as opposed to bad, helps put a paper wall between the killers and other members of society who may, in fact, not be that dissimilar.

Often these debates are not necessary as the killer is clearly part of a recognised terrorist group or ideology. In these situations, the label of bad fits easier.

The reasons why some people become terrorists are often associated with a toxic mix of political, social and personal dynamics. At the core are often feelings of alienation, offset by an offer of identity, purpose and significance within a new community that nurtures them against a perceived enemy that is threatening them, their culture or the political worldview they aspire to. These killers then belief that direct actions involving extreme violence against unarmed civilians is legitimate, as the existing political systems have failed them.

These people understand the implications of their decisions. But they come to conclusions which are the antithesis of what the majority of people believe. This is not to suggest that the killers are psychopaths. Mass murderers often do have a conscience and feel empathy, but in very limited circles. Fundamentally, they are not mad.

Of course, much of what is written about the psychology of mass murder is guess work. Terrorists and mass murderers don’t usually volunteer as experimental subjects, and questions to the the killers are often impossible as they are also killed during their acts of violence. This means that the psychology in this area is marked more by theory and opinion than by good science.

Making psychology fit into Law

Unfortunately, this conclusion is not satisfactory for the courts in the few instances where defendants have been captured and have left behind clear links to a political ideology, such as a manifesto. These people must have their psychological conditions forced into legal definitions, as a way of attributing responsibility, or not.

The first stage of the legal process, when the question of whether an accused is mad or bad is asked, is when they are examined to see if they are “unfit to stand trial”. In New Zealand, this means a defendant may avoid trial if they are unable, due to mental impairment, to conduct a defence or to instruct their counsel to do so.

This includes those who are unable to understand the purpose or possible consequences of the proceedings. Mental impairment is taken to include both mental disorder (a state of mind characterised by delusions or by disorders of mood or perception to such a degree that it poses a serious danger to that person or others) and intellectual disability.

Read more: Explainer: trial of alleged perpetrator of Christchurch mosque shootings

It was this stage of the comparable legal proceedings that caused such difficulty with a Norwegian far-right terrorist, who in 2011 killed 77 people and left behind a manifesto which was emailed to over 1000 addresses 90 minutes before the attack. Psychiatric experts initially classified him as unfit to stand trial because he was found to be “psychotic” during the attack. Following a public outcry, a second report, in which the murderer cooperated, came to the opposite conclusion. It found that although he may have had a personality disorder, he was not psychotic at the time of the attack. This meant he proceeded to trial.

A possible finding of mental impairment or a personality disorder does not mean that the accused is legally insane. The insanity, as in law of New Zealand, signifies a severe mental illness producing significant incapacity to understand the factual or moral quality (having regard to the commonly accepted standards of right and wrong) of one’s actions. While many legally insane offenders may also be mentally impaired, not all mentally impaired people are insane. These people may retain sufficient mental capacity to be held legally responsible for their actions.

But even if someone is fit to stand trial, the option of pleading insanity remains. However, such an option is often not popular with people accused of terror or mass-murder. The man known as the Unabomber, who also left behind a manifesto, examined this option at his hearing after his lawyers recommended pleading insanity as a way to avoid the death penalty when he was tried in the United States. He refused to go along with this defence strategy, preferring to plead guilty, rather than let posterity think he was of unsound mind.

Authors: Alexander Gillespie, Professor of Law, University of Waikato