More grey tsunami than youthquake: despite record youth enrolments, Australia’s voter base is ageing

- Written by Danielle Wood, Program Director, Budget Policy and Institutional Reform, Grattan Institute

The 2019 election has been heralded as a “generational election” or an “age war”. Labor goes to the election with a series of policies on climate change, housing affordability, wages and budget sustainability clearly designed to appeal to young and middle-aged Australians concerned about their future.

But while the record numbers of enrolled young voters may make this look like a political masterstroke, the fact remains that the Australia’s voter base, like its population, is ageing. Baby boomers will remain a political force in this country for some time to come.

Youth enrolment is rising, but not just because of the marriage equality plebiscite

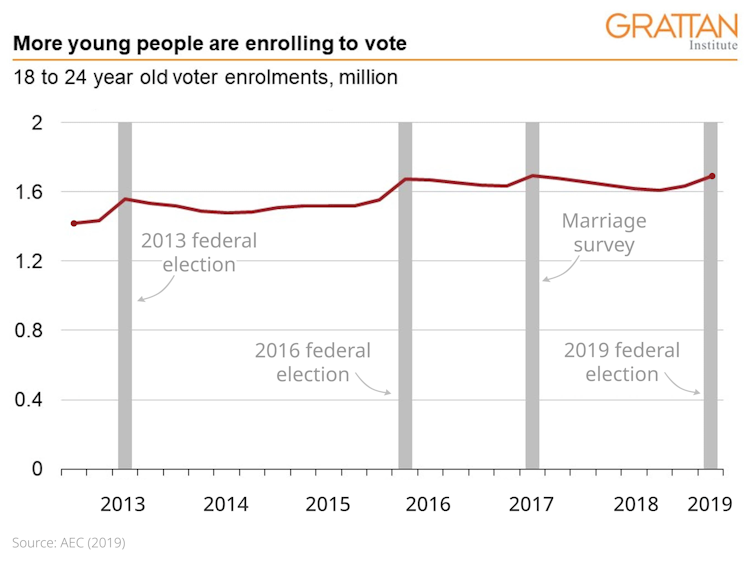

Youth voter enrolment is at an all-time high, with 88.8% of eligible 18- to 24-year-olds — some 1.7 million Australians — enrolled to vote. This is somewhat higher than the previous peaks for the marriage equality plebiscite (88.6%) and the 2016 election (86.7%).

Many commentators have credited the marriage equality plebiscite with driving increased youth engagement and participation. Between August 8 and 24, 2017, in the lead-up to the plebiscite, the Australian Electoral Commission added almost 100,000 people to the electoral roll. Around two-thirds of these were aged 18 to 24.

But while the numbers sound impressive, this uptick in youth enrolment was actually smaller than the normal increase we see before a federal election.

Around 300,000 Australians turn 18 every year, so younger voters are continually being added to the electoral roll. However, many new voters — whether new citizens or young Australians who have recently turned 18 — complete their enrolment paperwork in the lead-up to elections. This is why we see a sharp increase in enrolments, and particularly in youth enrolments, in the months before a poll.

Enrolments for 18- to 19-year-olds jumped by more than 80,000 people in the final weeks before the 2013 and 2016 elections. In contrast, net enrolments only grew by around 48,000 for the 18-19 age group in the weeks prior to the marriage plebiscite.

Because the marriage equality plebiscite was held in the normal three-year window between elections, it probably brought forward some of the enrolments that would normally have occurred in the lead-up to the 2019 election. But it is not clear that the plebiscite had the sizeable and lasting effect on youth enthusiasm that has been claimed. Enrolments for under-25s for the 2019 election are around 2 percentage points higher than for the 2016 federal election.

The more significant change in youth enrolments occurred between 2013 and 2016, and for reasons that had little to do with any increased political engagement among young people.

In 2012, the government empowered the AEC to directly enrol citizens (and update their details) once it had sufficient information from other government agencies, including Centrelink and the national driver licence database. The AEC also introduced entirely online enrolments in the lead-up to the 2013 election.

The AEC says direct enrolment resulted in almost 279,000 new enrolments between the 2013 and 2016 elections; online enrolments accounted for another 365,000.

An ageing population means an ageing voter base

The effect of an ageing voter population dwarfs the modest growth in youth enrolments.

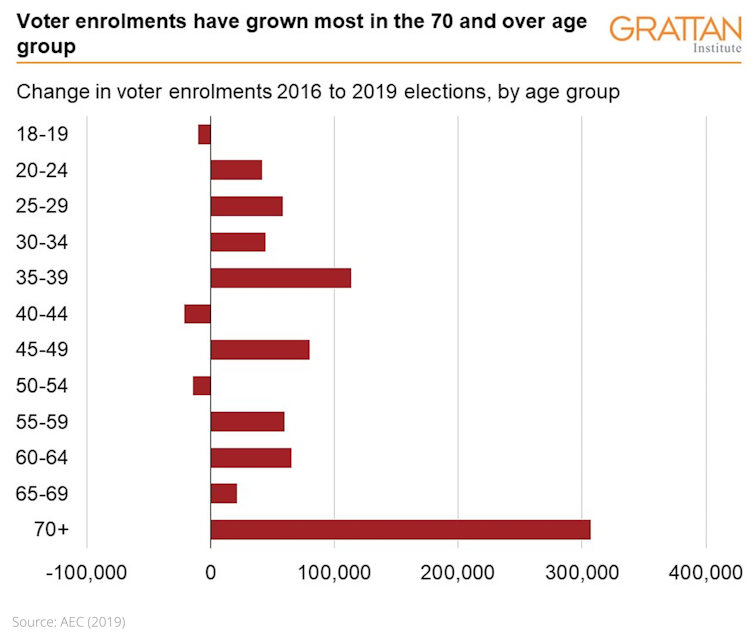

The biggest change in voter demographics since the last federal election in 2016 was the enormous growth in voters aged 70 and over. As Australians live longer and healthier lives, voters will, on average, be older.

Many commentators have credited the marriage equality plebiscite with driving increased youth engagement and participation. Between August 8 and 24, 2017, in the lead-up to the plebiscite, the Australian Electoral Commission added almost 100,000 people to the electoral roll. Around two-thirds of these were aged 18 to 24.

But while the numbers sound impressive, this uptick in youth enrolment was actually smaller than the normal increase we see before a federal election.

Around 300,000 Australians turn 18 every year, so younger voters are continually being added to the electoral roll. However, many new voters — whether new citizens or young Australians who have recently turned 18 — complete their enrolment paperwork in the lead-up to elections. This is why we see a sharp increase in enrolments, and particularly in youth enrolments, in the months before a poll.

Enrolments for 18- to 19-year-olds jumped by more than 80,000 people in the final weeks before the 2013 and 2016 elections. In contrast, net enrolments only grew by around 48,000 for the 18-19 age group in the weeks prior to the marriage plebiscite.

Because the marriage equality plebiscite was held in the normal three-year window between elections, it probably brought forward some of the enrolments that would normally have occurred in the lead-up to the 2019 election. But it is not clear that the plebiscite had the sizeable and lasting effect on youth enthusiasm that has been claimed. Enrolments for under-25s for the 2019 election are around 2 percentage points higher than for the 2016 federal election.

The more significant change in youth enrolments occurred between 2013 and 2016, and for reasons that had little to do with any increased political engagement among young people.

In 2012, the government empowered the AEC to directly enrol citizens (and update their details) once it had sufficient information from other government agencies, including Centrelink and the national driver licence database. The AEC also introduced entirely online enrolments in the lead-up to the 2013 election.

The AEC says direct enrolment resulted in almost 279,000 new enrolments between the 2013 and 2016 elections; online enrolments accounted for another 365,000.

An ageing population means an ageing voter base

The effect of an ageing voter population dwarfs the modest growth in youth enrolments.

The biggest change in voter demographics since the last federal election in 2016 was the enormous growth in voters aged 70 and over. As Australians live longer and healthier lives, voters will, on average, be older.

Around 300,000 more voters age 70 and over are enrolled to vote now than for the 2016 election, a 13% increase in just three years. In the same period, enrolments for younger voters aged 18 to 34 have only grown by around 135,000, or 3%.

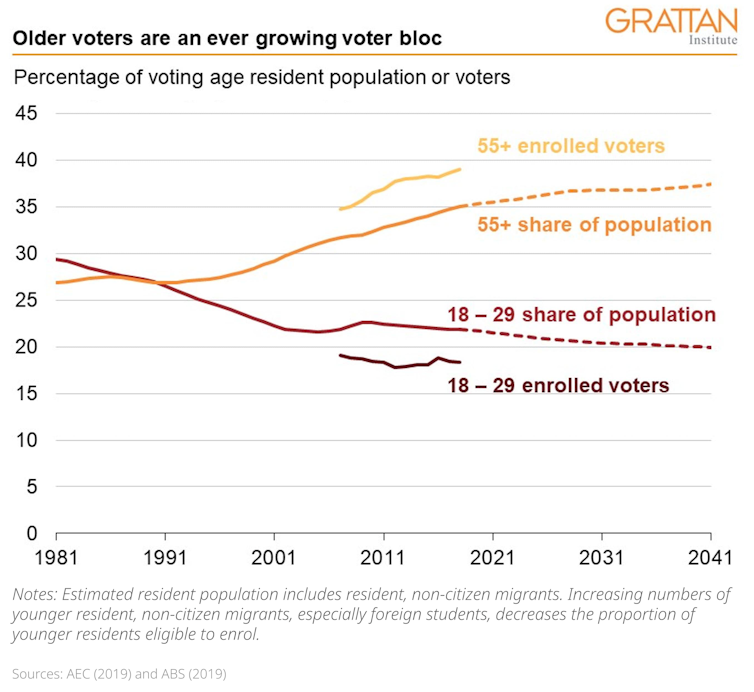

The recent increase in older voters is part of a long-term trend towards an ageing population overall. The first time Australia had more residents 55 and over than aged 18 to 29 was in 1991. Since then, the relative share of those 55 and older has continued to increase and is forecast to grow further over the next two decades.

Around 300,000 more voters age 70 and over are enrolled to vote now than for the 2016 election, a 13% increase in just three years. In the same period, enrolments for younger voters aged 18 to 34 have only grown by around 135,000, or 3%.

The recent increase in older voters is part of a long-term trend towards an ageing population overall. The first time Australia had more residents 55 and over than aged 18 to 29 was in 1991. Since then, the relative share of those 55 and older has continued to increase and is forecast to grow further over the next two decades.

Older Australian residents are also more likely to be citizens than younger Australians because new residents tend to be younger than the average Australian. This factor decreases the relative proportion of younger Australian residents enrolled to vote.

How might this affect the election outcome?

If Labor is relying on a surge of younger voters to deliver it victory then its hopes may be misplaced. Of course, that doesn’t mean a platform focused on some of the environmental and economic concerns of younger Australians cannot succeed.

But it does suggest that electoral success will depend on persuading enough older voters that Labor’s proposals can provide future generations with the same standard of living that they have enjoyed.

Older Australian residents are also more likely to be citizens than younger Australians because new residents tend to be younger than the average Australian. This factor decreases the relative proportion of younger Australian residents enrolled to vote.

How might this affect the election outcome?

If Labor is relying on a surge of younger voters to deliver it victory then its hopes may be misplaced. Of course, that doesn’t mean a platform focused on some of the environmental and economic concerns of younger Australians cannot succeed.

But it does suggest that electoral success will depend on persuading enough older voters that Labor’s proposals can provide future generations with the same standard of living that they have enjoyed.

Authors: Danielle Wood, Program Director, Budget Policy and Institutional Reform, Grattan Institute