The government and tech companies can't prevent 'fake news' during the election – only the public can

- Written by Michael Jensen, Senior Research Fellow, Institute for Governance and Policy Analysis, University of Canberra

We’re only days into the federal election campaign and already the first instances of “fake news” have surfaced online.

Over the weekend, Labor demanded that Facebook remove posts it says are “fake news” about the party’s plans to introduce a “death tax” on inheritances. Labor also called on the Coalition to publicly disavow the misinformation campaign.

An inauthentic tweet purportedly sent from the account of Australian Council of Trade Unions secretary Sally McManus also made the rounds, claiming that she, too, supported a “death tax”. It was retweeted many times – including by Sky News commentator and former Liberal MP Gary Hardgrave – before McManus put out a statement saying the tweet had been fabricated.

What the government and tech companies are doing

In the wake of the cyber-attacks on the 2016 US presidential election, the Australian government began taking seriously the threat that “fake news” and online misinformation campaigns could be used to try to disrupt our elections.

Last year, a taskforce was set up to try to protect the upcoming federal election from foreign interference, bringing together teams from Home Affairs, the Department of Finance, the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC), the Australian Federal Police (AFP) and the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO).

The AEC also created a framework with Twitter and Facebook to remove content deemed to be in violation of Australian election laws. It also launched an aggressive campaign to encourage voters to “stop and consider” the sources of information they consume online.

For their part, Facebook and Twitter rolled out new features aimed specifically at safeguarding the Australian election. Facebook announced it would ban foreign advertising in the run-up to the election and launch a fact-checking partnership to vet the accuracy of information being spread on the platform. However, Facebook will not be implementing requirements that users wishing to post ads verify their locations until after the election.

Twitter also implemented new rules requiring that all political ads be labelled to show who sponsored them and those sending the tweets to prove they are located in Australia.

While these moves are all a good start, they are unlikely to be successful in stemming the flow of manipulative content as election day grows closer.

Holes in the system

First, a foreign entity intent on manipulating the election can get around address verification rules by partnering with domestic actors to promote paid advertising on Facebook and Twitter. Furthermore, Russia’s intervention in the US election showed that “troll” or “sockpuppet” accounts, as well as botnets, can easily spread fake news content and hyperlinks in the absence of a paid promotion strategy.

Facebook has also implemented measures that actually reduce transparency in its advertising. To examine how political advertising works on the platform, ProPublica built a browser plugin last year to collect Facebook ads and show which demographic groups they were targeting. Facebook responded by blocking the plugin. The platform’s own ad library, while expansive, also does not include any of the targeting data that ProPublica had made public.

Read more: Russian trolls targeted Australian voters on Twitter via #auspol and #MH17

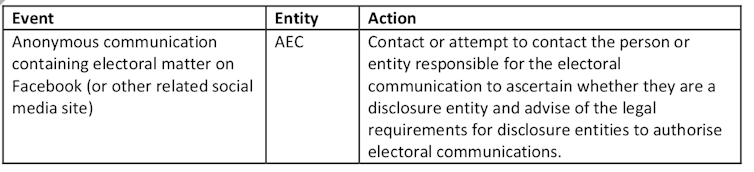

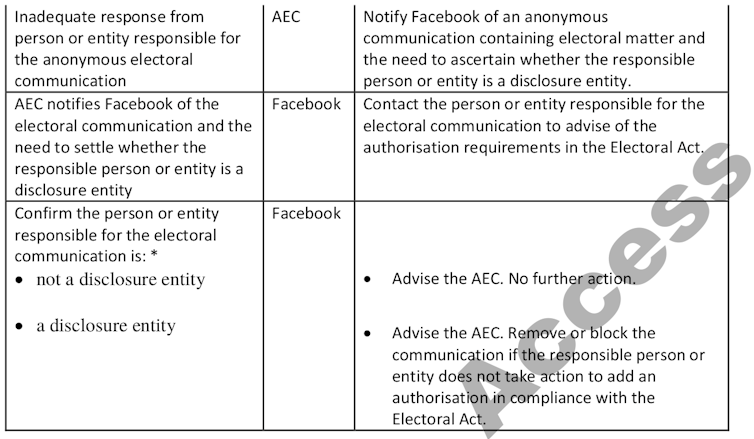

A second limitation faced by the AEC, social media companies, and government agencies is timing. The framework set up last year by the AEC to address content in possible violation of electoral rules has proven too slow to be effective. First, the AEC needs to be alerted to questionable content. Then, it will try to contact whoever posted it, and if it can’t, the matter is escalated to Facebook. This means that days can pass before the material is addressed.

Last year, for instance, when the AEC contacted Facebook about sponsored posts attacking left-wing parties from a group called Hands Off Our Democracy, it took Facebook more than a month to respond. By then, the group’s Facebook page had disappeared.

FOI request by ABC News, Author provided

FOI request by ABC News, Author provided

Portions of AEC letter to Facebook legal team for Australia and New Zealand detailing steps for addressing questionable content, sent 30 August 2018.

FOI request by ABC News, Author provided

The length of time required to take down illegal content is critical because research on campaigning shows that the window of opportunity to shift a political discussion on social media is often quite narrow. For this reason, an illegal ad likely will have achieved its purpose by the time it is flagged and measures are taken to remove it.

Indeed, from 2015 to 2017, Russia’s Internet Research Agency, identified by US authorities as the main “troll farm” behind Russia’s foreign political interference, ran over 3,500 ads on Facebook with a median duration of just one day.

Even if content is flagged to the tech companies and accounts are blocked, this measure itself is unlikely to deter a serious misinformation campaign.

The Russian Internet Research Agency spent millions of dollars and conducted research over a period of years to inform their strategies. With this kind of investment, a determined actor will have gamed out changes to platforms, anticipated legal actions by governments and adapted its strategies accordingly.

What constitutes ‘fake news’ in the first place?

Finally, there is the problem of what counts as “fake news” and what counts as legitimate political discussion. The AEC and other government agencies are not well positioned to police truth in politics. There are two aspects to this problem.

The first is the majority of manipulative content directed at democratic societies is not obviously or demonstrably false. In fact, a recent study of Russian propaganda efforts in the United States found the majority of this content “is not, strictly speaking, ‘fake news’.”

Instead, it is a mixture of half-truths and selected truths, often filtered through a deeply cynical and conspiratorial worldview.

There’s a different issue with the Chinese platform WeChat, where there is a systematic distortion of news shared on public or “official accounts”. Research shows these accounts are often subject to considerable censorship – including self-censorship – so they do not infringe on the Chinese government’s official narrative. If they do, the accounts risk suspension or their posts can be deleted.. Evidence shows that official WeChat accounts in Australia often change their content and tone in response to changes in Beijing’s media regulations.

Read more:

Who do Chinese-Australian voters trust for their political news on WeChat?

For this reason, suggestions that platforms like WeChat be considered “an authentic, integral part of a genuinely multicultural, multilingual mainstream media landscape” are dangerously misguided, as official accounts play a role in promoting Beijing’s strategic interests rather than providing factual information.

The public’s role in stamping out the problem

If the AEC is not in a position to police truth online and combat manipulative speech, who is?

Research suggests that in a democracy, the political elites play a strong role in shaping opinions and amplifying the effects of foreign influence misinformation campaigns.

For example, when Republican John McCain was running for the US presidency against Barack Obama in 2008, he faced a question at a rally about whether Obama was “an Arab” – a lie that had been spread repeatedly online. Instead of breathing more life into the story, McCain provided a swift rebuttal.

After the Labor “death tax” Facebook posts appeared here last week, some politicians and right-wing groups shared the post on their own accounts. (It should be noted, however, that Hardgrave apologised for retweeting the fake tweet by McManus.)

Beyond that, the responsibility for combating manipulative speech during elections falls to all citizens. It’s absolutely critical in today’s world of global digital networks for the public to recognise they “are combatants in cyberspace”.

The only sure defence against manipulative campaigns – whether from foreign or domestic sources – is for citizens to take seriously their responsibilities to critically reflect on the information they receive and separate fact from fiction and manipulation.

Portions of AEC letter to Facebook legal team for Australia and New Zealand detailing steps for addressing questionable content, sent 30 August 2018.

FOI request by ABC News, Author provided

The length of time required to take down illegal content is critical because research on campaigning shows that the window of opportunity to shift a political discussion on social media is often quite narrow. For this reason, an illegal ad likely will have achieved its purpose by the time it is flagged and measures are taken to remove it.

Indeed, from 2015 to 2017, Russia’s Internet Research Agency, identified by US authorities as the main “troll farm” behind Russia’s foreign political interference, ran over 3,500 ads on Facebook with a median duration of just one day.

Even if content is flagged to the tech companies and accounts are blocked, this measure itself is unlikely to deter a serious misinformation campaign.

The Russian Internet Research Agency spent millions of dollars and conducted research over a period of years to inform their strategies. With this kind of investment, a determined actor will have gamed out changes to platforms, anticipated legal actions by governments and adapted its strategies accordingly.

What constitutes ‘fake news’ in the first place?

Finally, there is the problem of what counts as “fake news” and what counts as legitimate political discussion. The AEC and other government agencies are not well positioned to police truth in politics. There are two aspects to this problem.

The first is the majority of manipulative content directed at democratic societies is not obviously or demonstrably false. In fact, a recent study of Russian propaganda efforts in the United States found the majority of this content “is not, strictly speaking, ‘fake news’.”

Instead, it is a mixture of half-truths and selected truths, often filtered through a deeply cynical and conspiratorial worldview.

There’s a different issue with the Chinese platform WeChat, where there is a systematic distortion of news shared on public or “official accounts”. Research shows these accounts are often subject to considerable censorship – including self-censorship – so they do not infringe on the Chinese government’s official narrative. If they do, the accounts risk suspension or their posts can be deleted.. Evidence shows that official WeChat accounts in Australia often change their content and tone in response to changes in Beijing’s media regulations.

Read more:

Who do Chinese-Australian voters trust for their political news on WeChat?

For this reason, suggestions that platforms like WeChat be considered “an authentic, integral part of a genuinely multicultural, multilingual mainstream media landscape” are dangerously misguided, as official accounts play a role in promoting Beijing’s strategic interests rather than providing factual information.

The public’s role in stamping out the problem

If the AEC is not in a position to police truth online and combat manipulative speech, who is?

Research suggests that in a democracy, the political elites play a strong role in shaping opinions and amplifying the effects of foreign influence misinformation campaigns.

For example, when Republican John McCain was running for the US presidency against Barack Obama in 2008, he faced a question at a rally about whether Obama was “an Arab” – a lie that had been spread repeatedly online. Instead of breathing more life into the story, McCain provided a swift rebuttal.

After the Labor “death tax” Facebook posts appeared here last week, some politicians and right-wing groups shared the post on their own accounts. (It should be noted, however, that Hardgrave apologised for retweeting the fake tweet by McManus.)

Beyond that, the responsibility for combating manipulative speech during elections falls to all citizens. It’s absolutely critical in today’s world of global digital networks for the public to recognise they “are combatants in cyberspace”.

The only sure defence against manipulative campaigns – whether from foreign or domestic sources – is for citizens to take seriously their responsibilities to critically reflect on the information they receive and separate fact from fiction and manipulation.

Authors: Michael Jensen, Senior Research Fellow, Institute for Governance and Policy Analysis, University of Canberra