Getting away with it … sort of. How a dictator and a fugitive Nazi advanced international human rights law

- Written by Olivera Simic, Professor in Law, Griffith University

Pinochet and Rauff? They were alike. Each had two faces. One gentle, the other hard. They were joined.

And they both got away with it … Sort of.

Philippe Sands loves to tell stories. A master of historical non-fiction, he has become known for his unique blend of deeply personal, legal and historical narratives, which weave together incredible coincidences with moving stories of human courage in the face of mass atrocities and horror.

Sands is a leading practitioner of international law, a professor at University College London, an author, a playwright, and the recipient of numerous literary awards. He is also someone whose family was murdered in the vortex of the Holocaust in Ukraine.

With his previous two books, East West Street: On the Origins of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity (2016) and The Ratline: Love, Lies and Justice on the Trail of a Nazi Fugitive (2020), he demonstrated his unique skill in presenting complex legal cases to avid readers.

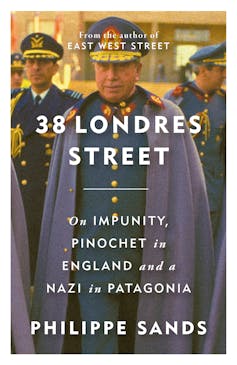

His latest book, 38 Londres Street: On Impunity, Pinochet in England and a Nazi in Patagonia, rounds out the trilogy.

If it weren’t based on facts, one might think it was a brilliantly crafted thriller.

Review: 38 Londres Street: On Impunity, Pinochet in England and a Nazi in Patagonia – Philippe Sands (Weidenfeld & Nicolson)

38 Londres Street weaves together several narratives, but at its heart is the story of the legal attempts to end impunity for two accused criminals. One is Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet. The other is Walther Rauff, a former SS officer who fled to South America and allegedly worked with Pinochet’s Secret Intelligence Service.

Sands brings these two men into a single narrative to highlight the legal struggle against impunity for mass atrocities, though he never loses sight of the victims and their human stories of suffering, courage and persistence.

These were people whose lives were abruptly and violently taken. Sands includes many of their names and tragic fates in his book. He informs his readers that the Cementerio Sara Braun in Punta Arenas, Chile, has a memorial bearing the names of Pinochet’s many victims. He clearly wants these individuals never to be forgotten.

Universal jurisdiction and the Pinochet precedent

The building at 38 Londres Street in Santiago was once a site of pain. At this secret interrogation centre, one of many across Santiago and the rest of Chile, Pinochet’s agents imprisoned, tortured, executed and disappeared tens of thousands of people deemed leftists, socialists, communists or “other undesirables”.

Pinochet came to power on September 11, 1973, overthrowing the democratically elected socialist government of President Salvador Allende in a military coup. He would rule Chile with an iron fist until 1990.

Chile’s youth became the targets of his murderous regime. Sands notes that most victims were between 21 and 30 years old. The majority of them were workers; the rest mainly comprised academics, professionals and students. The atrocities were committed with impunity.

Like all dictators, Pinochet believed himself untouchable. But in October 1998, while visiting the UK, he was arrested in London. Spanish judge Baltasar Garzón was seeking Pinochet’s extradition to Spain in order to try him for human rights abuses.

Garzón was acting under the then-controversial legal principle of universal jurisdiction, which allows courts in one country to prosecute grave human rights violations committed outside its borders, regardless of the nationality of the accused.

Never before had a former head of state of one country been arrested by, and in another, for committing international crimes.

Sands would become involved in one of the most famous cases in international law since the Nuremberg trials more than 50 years earlier. Pinochet’s lawyers offered him an opportunity to participate in the case, arguing for the former dictator’s immunity as a former head of state. His wife threatened to divorce him if he accepted.

He declined the offer. Instead, Sands represented Human Rights Watch when the Pinochet case was considered by the Law Lords.

Pinochet had been indicted for crimes against humanity and genocide. At issue was the question of whether Pinochet, as a former head of state, had immunity before the English courts for acts committed in another country while he was in office. Should there be a legal protection for former dictators?

The proceedings in London were novel and remarkable, writes Sands, because this was an open legal question when Pinochet was arrested. His arrest raised an unprecedented issue: was there an exception to the rule of immunity for a former head of state when a crime in international law was involved? And did the exception apply before a national court, rather than an international one?