Teeth 'time capsule' reveals that 2 million years ago, early humans breastfed for up to 6 years

- Written by Renaud Joannes-Boyau, Senior research fellow, Southern Cross University

Humans’ distant ancestor Australopithecus africanus had a unique approach to raising their young, as shown in our new research published today in Nature.

Geochemical analysis of four teeth shows they exclusively breastfed infants for about 6-9 months, before supplementing breast milk with varying amounts of solid food until they were 5-6 years old. The balance between milk and solid food in this period varied cyclically, probably in response to seasonal changes in food availability.

Read more: How we calculated the age of caves in the Cradle of Humankind -- and why it matters

This knowledge is useful on several fronts. From an evolutionary point of view, it helps us understand the particular biological and behavioural adaptations of Australopithecus africanus compared to other extinct human ancestors and modern humans.

However, breastfeeding for up to 5-6 years is metabolically expensive – it requires a certain input of calories for the lactating mother. Using milk as a supplemental food for older offspring may have hampered the ability of the A. africanus species to successfully survive during a period of substantially changing climate.

Perhaps this way of life hastened the extinction of A. africanus around 2 million years ago.

A puzzling hominin

A. africanus was first discovered in 1924 by Australian-born scientist Raymond Dart at Taung in South Africa, and represented the first early human ancestor identified from Africa.

A century of excavation and research later, Taung and other sites across South Africa produced a rich record of early human ancestors. This region is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site known as “The Cradle of Humankind”.

This hominin species, a member of the human evolutionary lineage, had a mixture of ape-like characteristics and more specialised ones. It has only been recovered from fossil sites in South Africa that date to between 3 million and 2 million years ago.

Because only a few specimens exist, we have little information about how A. africanus lived and its relationship to other fossil hominin species such as the eastern African species of Australopithecus, the robust Paranthropus, and our own genus, Homo.

Illustration of a mother Australopithecus africanus and her young offspring.

Jose Garcia and Renaud Joannes-Boyau

Illustration of a mother Australopithecus africanus and her young offspring.

Jose Garcia and Renaud Joannes-Boyau

Zapping teeth

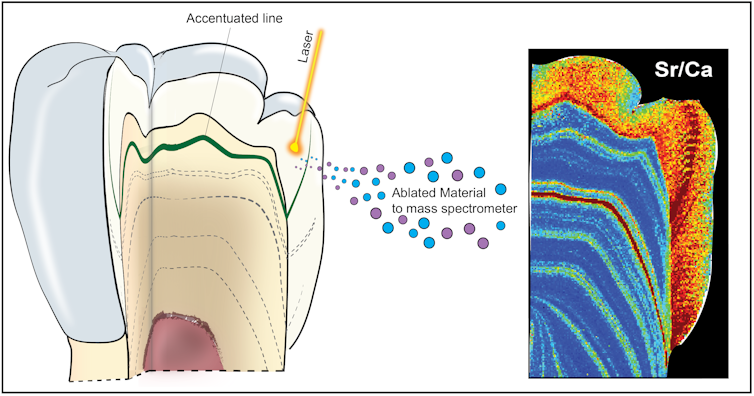

Our research takes advantage of cutting-edge analytical techniques. We used a laser to zap tiny pieces off fossil teeth, and then used an instrument called a mass spectrometer to determine their chemical composition.

This is much less destructive than traditional methods that require the sample to be crushed and dissolved before analysis. This makes it a crucial technique for rare specimens such as those of A. africanus.

Our laser method also allowed us to map the composition of a specimen across the entire surface of a tooth – illuminating changes in diet, mobility or climate through time. This is an important advance, as it can reveal information that has been impossible to establish using conventional palaeontological methods.

Schematic diagram of the use of laser ablation analysis to map the concentration of strontium and uranium within a tooth.

Renaud Joannes-Boyau, Author provided

Schematic diagram of the use of laser ablation analysis to map the concentration of strontium and uranium within a tooth.

Renaud Joannes-Boyau, Author provided

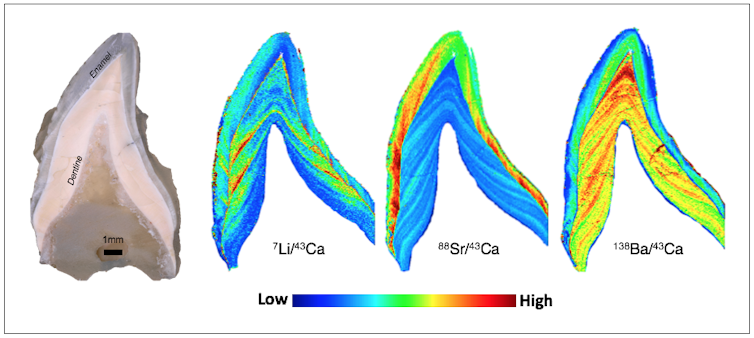

In this study, we mapped changes in the concentration of barium, strontium and lithium in fossil teeth of two individuals. The amounts of these elements in our bodies can change significantly depending on our diet, and these changes are reflected in the composition of our bones and teeth.

While our bones continue to change composition as they remodel during our lives, our teeth don’t change after they form during childhood. Teeth are thus a perfect chemical time capsule of our childhood diet.

Read more: What teeth can tell about the lives and environments of ancient humans and Neanderthals

Mapping a varied diet

The concentration of barium in breast milk is very high, so infant teeth that form during breastfeeding will also have a high concentration of this element. This concentration gradually drops as other sources of food are introduced.

The samples we analysed from A. africanus show a different pattern, with cyclical fluctuations in barium concentration. This suggests mothers would increase or reduce the amount of additional food, probably depending on the availability of other resources. This is an adaptation to food stress also used by modern orangutans.

The concentration of lithium in these teeth also varies cyclically, although not always at the same time as barium. The precise cause of lithium variations is still unclear but it seems to be linked to variations in body fat reserves or how much protein is eaten.

This suggests A. africanus regularly faced food stress, causing their diet and/or fat reserves to change with the seasons.

Australopithecus africanus canine showing a first period of nursing behaviour followed by a cyclical signal in the lithium, strontium and barium distribution.

Renaud Joannes-Boyau

Australopithecus africanus canine showing a first period of nursing behaviour followed by a cyclical signal in the lithium, strontium and barium distribution.

Renaud Joannes-Boyau

We compared the results from A. africanus to modern animals from similar savannah biome regions, which supported our results by showing cyclical signal linked to seasonal variations mix with another signal interpreted as cyclical breastfeeding also seen in mdoern orangutans.

Close to home

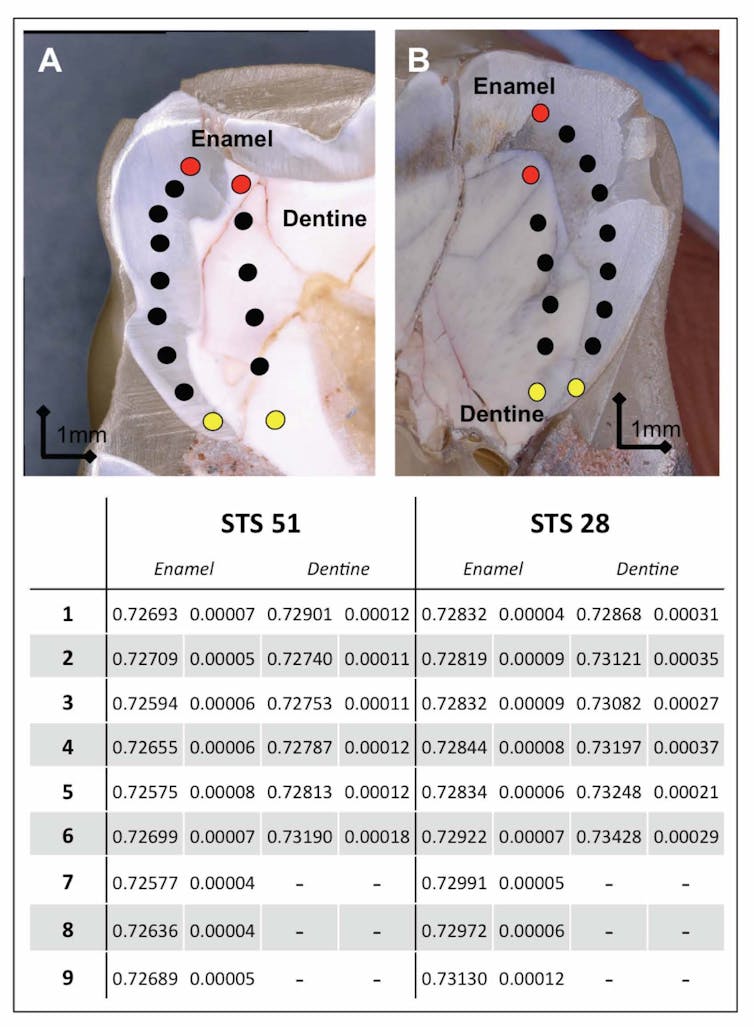

We also investigated the strontium isotope composition of these teeth to help understand where A. africanus was moving through the landscape. Isotopes of the same element can be distinguished by their mass.

Strontium isotopes are often used for this purpose in palaeontology, as different regions have characteristic isotope values that are taken up through food and drink.

The two A. africanus individuals in our study seemed to have lived most of their lives near the Sterkfontein cave where their remains were found.

Strontium isotopic ratio along the growth axis of an Australopithecus africanus tooth.

Renaud Joannes-Boyau

Strontium isotopic ratio along the growth axis of an Australopithecus africanus tooth.

Renaud Joannes-Boyau

Living in a region with limited food resources meant these early hominins would have eaten lots of different kinds of foods collected from varying habitats in order to survive.

Our research provides the first understanding of the nursing behaviour of A. africanus. We now know this hominin had an extended period of breastfeeding supplemented by varying amounts of solid food that caused their fat reserves to fluctuate significantly.

This was likely part of a largely successful survival strategy for the species.

But as ecosystems changed with climate around 2 million years ago, the metabolic stress on mothers may have contributed to the eventual extinction of this species.

Authors: Renaud Joannes-Boyau, Senior research fellow, Southern Cross University