To enable healing, there's a more effective way to Close the Gap in employment in remote Australia

- Written by Zoe Staines, ARC DECRA Research fellow, The University of Queensland

Talk of healing, care, and well-being is woven throughout the refreshed Closing the Gap agreement. These things were also central to Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s announcement of the Closing the Gap implementation package this week.

As part of the package, the government launched a redress scheme to support “intergenerational healing”, though this was really in response to a class action by survivors of the Stolen Generations.

The package also directs additional funding to Aboriginal community-controlled health organisations to “maintain the high level of care they offer”.

Recognition of the significant violence perpetrated by the settler state and measures to support healing are welcome and long overdue. However, history gives us good reason to be sceptical of the government’s lofty Closing the Gap rhetoric around pursuing improved well-being.

If improved well-being is supposed to underpin the refreshed Closing the Gap approach, then this must filter into all actions taken under the framework. However, measures to promote healing and care will only be treating the symptoms and not the cause while governments continue inflicting harm on Indigenous people.

We use the example of employment policy (targets 7 and 8 in the Closing the Gap agreement) in remote areas to show how government policies continue to create damage that must later be healed.

Stop punishing the unemployed in remote Australia

Since 2015, Indigenous peoples living remotely have been routinely punished under the Community Development Program (CDP). CDP requires individuals on income support payments to complete activities (like job searches and “work for the dole”) to receive their social security benefits. These activities were mandatory from 2015–20, though work for the dole was recently made voluntary.

CDP has roughly 40,000 participants, around 80% of whom are Indigenous. So harsh was this policy that the Commonwealth government has been taken to court by one remote council that claims the program is racist.

The introduction of the punitive scheme has hardly budged the number of Indigenous people in work, with employment numbers barely rising in remote Australia between 2008 and 2018–19.

However, mass unemployment is not a result of people choosing to remain on welfare. There are just not enough jobs for everyone. Consequently, attempts to close the “employment gap” in remote Australia by targeting the attitudes and behaviours of the unemployed have failed because they ignore the real cause: unemployment is structural, not behavioural.

CDP has meanwhile caused significant harm and torn at the social fabric of remote communities. It has disproportionately high levels of penalties and payment suspensions, which have lowered already impoverished household incomes.

Low rates of social security in places where food is extremely expensive results in “real hunger” and worsening physical and mental health. CDP activities also redirect people away from other important work, like caring for family and kin.

CDP is a dire example of how, on the one hand, the government talks about wanting to enable healing, while on the other hand, its own policies are a significant cause of ongoing harm.

Still listed in the Closing the Gap plan

In a welcome announcement around the time of the 2021–22 budget, the Morrison government committed to abolish CDP and replace it with a new “co-designed” program from 2023.

Yet, CDP remains listed in the Commonwealth’s implementation plan as an “action” that will contribute to closing the gap on “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people engaged in employment or education” (target 7).

Indeed, the Commonwealth did not announce any new initiatives yesterday that will assist in meeting its employment targets.

The failure of CDP provides an opportunity to carefully reconsider its harmful effects and to move forward in a manner consistent with Closing the Gap commitments around healing, caring, and ensuring well-being.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations have expressed optimism about the new targets, but say evidence-based programs must be prioritised.

Lukas Coch/AAP

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations have expressed optimism about the new targets, but say evidence-based programs must be prioritised.

Lukas Coch/AAP

Care work for people, Country and culture

There are unquestionable health and well-being benefits associated with work. However, if future policy looks to support people to engage in work, then suitable work must be available.

Pathways into waged jobs will only be open to a minority of unemployed Indigenous peoples in remote Australia. Yet, there is much productive work already being done that is unpaid. Policies that deploy narrow definitions of “work” ignore these diverse forms of labour, which are critically important in supporting the strained social fabric of remote communities.

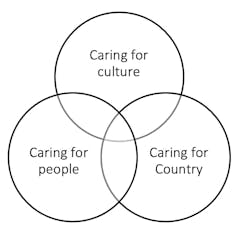

Care work should be supported in all its forms.

Care work should be supported in all its forms.

An example is care work: a term we use here to refer to caring for people, as well as for Country and culture — all of which are interlinked and mutually interdependent.

While some caring for Country and culture work is recognised and remunerated under the successful Indigenous ranger and language maintenance programs, much “caring for people” work remains unsupported and unpaid. Such work is overwhelmingly provided by Indigenous women.

If the Australian government is serious about supporting well-being and healing as key elements of Closing the Gap targets, then it must ensure care work in all its forms is supported, irrespective of its position within or beyond the formal economy.

Read more: How can the new Closing the Gap dashboard highlight what indicators and targets are on track?

Governments of all persuasions are increasingly embracing the notion of caring for Country. In the past 15 years, they have recognised, and more appropriately supported, Indigenous efforts in environmental healing.

We argue it is time that far greater emphasis is also placed on caring for people; a CDP replacement should have this objective as an underpinning feature.

The CDP overwhelmingly failed to care for people; its unintended consequence was to further deepen poverty and anomie. There will never be a better time to shift our policy focus in a positive direction as the nation reflects on our collective failure to Close the Gap, and as a new employment and income support program is being co-designed.

Authors: Zoe Staines, ARC DECRA Research fellow, The University of Queensland